by Dennis Crouch

It is time to pick-up our consideration of Supreme Court patent cases for the 2022-2023 term. A quick recap: Despite dozens of interesting and important cases, the Supreme Court denied all petitions for writ of certiorari for the 2021-2022 term. The most anticipated case last year was the 101 eligibility petition regarding automobile drive shaft manufacturing process. American Axle (cert denied). Bottom line, no patent cases were decided by the Court in the 2021-2022 term and none were granted certiorari for the new term starting this week.

The court’s first order of business comes on September 28, 2022 when it meets for the “long conference” to consider a fairly large pile of petitions that have piled-up over summer break. Of the 17 pending patent-focused petitions, 13 are set to be decided at the long conference. I have subjectively ordered the cases with the most important or most likely cases toward the top. Leading the pack are three cases focusing on “Full Scope” Enablement & Written Description. Topics:

- Enablement / Written Description (All three are biotech / pharma): 3 Cases;

- Infringement (FDA Labeling): 1 Case;

- Anticipation (On Sale Bar): 1 Case;

- Double Patenting (Still the law?): 1 Case;

- Procedure / Standing: 6 Cases;

- Eligibility (AmAxle Redux): 3 Cases; and

- Randomness (don’t bother with these): 2 Cases

1. Full Scope Written Description in Juno Therapeutics, Inc. v. Kite Pharma, Inc., No. 21-1566

According to the Federal Circuit, US patent law contains separate and distinct written description and enablement requirements. This case focuses on the required “written description of the invention” and challenges the court’s requirement that the specification demonstrate possession of “the full scope of the claimed invention” including unknown variations that fall within the claim scope.

Juno’s patent covers the highly successful and valuable CAR-T gene therapy. The claims require a “binding element” to bind T-cells to cancer cells. The specification does not provide much of any disclosure regarding how these binding cells actually work but instead states that binding elements are “known” and “routine” and cites to a decade-old article on the topic. The idea here is that the patentee did enough to enable someone to make and use the invention–isn’t that enough? But, the Federal Circuit concluded that the specification should have done more to disclose those binding elements, including all “known and unknown” elements covered by the claims.

Juno argues that the Federal Circuit’s test “is simply impossible to meet” for biotech inventions and is not part of the law envisioned by Congress. The argument on virtual impossibility is a centerpiece of several enablement/written description cases pending. Although the focus here is biotech, the same arguments are brewing with regard to AI-assisted inventions. In its responsive brief, Kite reiterates that “as precedent has held for over 50 years—§ 112’s requirement of a “written description” is distinct from the requirement to “enable any person skilled in the art to make and use the” invention.” That 50-year reference makes me chuckle because that is roughly the same period that Roe v. Wade was good law before being overturned by the Court last term.

The Federal Circuit’s decision in Juno was also a big deal because it overturned the jury verdict–holding that no reasonable jury could have found written description support. But, it is tough to get the Supreme Court to hear a review on detailed factual findings.

Chief Judge Moore issued the decision in the case that was joined by Judges Prost and O’Malley. The petition was filed by noted Jones Day attorney Greg Castanias along with former SG Noel Francisco and BMS (Juno) deputy GC Henry Hadad. Joshua Rosenkranz (Orrick) is running the show for the respondent Kite Pharma. The petition has been supported by five amicus briefs, the most of any pending case.

2. Written Description for an Effective Treatment in Biogen International GmbH v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc., No. 21-1567

If the Supreme Court grants certiorari in Juno, there is a good chance that it would also hear the parallel written description case of Biogen v. Mylan. Biogen’s patent claims is directed toward a drug treatment for multiple sclerosis. The treatment has one easy step: administer “a therapeutically effective amount [of] about 480 mg” of DMF per day along with an excipient for treatment of multiple sclerosis. The Federal Circuit found the claim lacked written description support — especially for a showing that 480 mg is an “effective” treatment. The specification expressly states that “an effective dose … can be from … about 480 mg to about 720 mg per day.” But, the court found that singular prophetic “passing reference” “at the end of one range among a series of ranges” was insufficient to actually the notion that the patentee possessed an “effective treatment” at the 480 mg dosage. Effectiveness is often relegated to the utility doctrine, but here it is an express claim limitation.

In some ways Biogen and Juno are both outliers–albeit at opposite ends of the spectrum. In Juno, the patentee is seeking a broad genus claim based upon a somewhat narrower disclosure while in Biogen, the patentee is seeking a quite narrow claim based upon a much more general disclosure. It is a forest-tree situation. If you describe several trees, can you claim possession of the forest? Likewise, if you describe the forest, can you claim possession of individual trees? Note also that there are similarities with the pending enablement petition in Amgen v. Sanofi as well as with the likely upcoming petition in Novartis Pharm. Corp. v. Accord Healthcare, Inc., 38 F.4th 1013 (Fed. Cir. 2022) (written description). The overlap between written description and enablement is inextricable. It is usually true that the arguments that prove or disprove written description have the same impact on enablement. But here in these cases the defendants and courts continue to reiterate the potential differences.

The decision was authored by Judge Reyna and joined by Judge Hughes. Judge O’Malley wrote in dissent. The court then denied en banc rehearing despite a dissenting opinion from Judge Lourie joined by Chief Judge Moore and Judge Newman. Supreme Court expert Seth Waxman is handling the petition along with his team from Wilmer. Nathan Kelley (Perkins) is representing Mylan. Kelley is the former USPTO Solicitor and PTAB Chief Judge.

3. Full Scope Enablement in Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, No. 21-757

Amgen also fits well as a companion case to Juno v. Kite. The difference is that Amgen asks about enablement rather than written description. Still, the focus is the same–does enabling “the invention” require enabling all potential embodiments (even those not yet comprehended by the patentee). As in Juno, the genus claim here is also functionally claimed, a feature that appears to make it more susceptible to invalidation under both WD and Enablement doctrines. I would have previously put this case even higher in the ranking, but the Gov’t recently filed an amicus brief in the case suggesting that the Court deny certiorari.

Jeff Lamkin (MoloLamkin) is representing the patentee Amgen in the petition. George Hicks (Kirkland) is counsel of record on the other side. The Gov’t CVSG brief was filed by folks at the DOJ SG’s. USPTO officials did not join. Although the internal politics are always unclear, this often means that the USPTO does not fully agree with the Gov’t position.

4. Skinny Label Infringement in Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. v. GlaxoSmithKline LLC, No. 22-37

This case delves deeply into the patent-FDA overlap and involves an increasingly common situation “skinny label” situation. The setup involves an unpatented drug with multiple clinical uses, only some of which are patented. What this means is that a generic producer should be permitted to market the drug for the unpatented uses, but excluded from marketing the drug for the patented uses. One problem here is that the healthcare payers are going to recognize that the drugs are interchangeable and very quickly start buying the generic version even for the unauthorized patented use. One way to think about this case is the level of responsibility that the generic manufacturer has to make sure that its drug is not used in an infringing way. At what point do sales-with-knowledge equate with inducement?

The particular question presented focuses on FDA-approved labels that carve-out patented uses. In the process, the FDA starts with the branded drug’s label and asks the brand manufacturer to identify which parts of the labeled uses are infringing. Those labelled uses are then deleted from the label. Teva and the FDA followed that exact process in this case. But, the courts found that the “skinny label” still encouraged infringement — part of the problem was that the infringing and non-infringing uses were so similar to one another. Petitioner here is seeking a safe-harbor, asking: “If a generic drug’s FDA-approved label carves out all of the language that the brand manufacturer has identified as covering its patented uses, can the generic manufacturer be held liable on a theory that its label still intentionally encourages infringement of those carved-out uses?”

Chief Judge Moore wrote the opinion in this case joined by Judge Newman. Judge Prost wrote in dissent. After an initial outcry, the panel issued a new opinion that toned-things down a bit and suggested that labelling will usually not be infringing, but that this was somehow an exceptional case. Subsequently the full court denied en banc rehearing, with Chief Judge Moore re-justifying her position while Judges Prost, Dyk, and Reyna all dissented. The jury had originally sided with GSK — finding infringement. However, the district court rejected the verdict and instead granted Teva’s motion for judgment as a matter of no infringement. Judge Stark who is now a member of the Federal Circuit was the district court judge in the case.

Willy Jay (Goodwin) is handling the petition; Juanita Brooks (Fish) is in opposition.

5. Post IPR Estoppel in Apple Inc. v. Caltech, No. 22-203 (Briefing ongoing)

This important case raises a question of statutory interpretation regarding post-IPR estoppel: Does IPR estoppel 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2) extend to all grounds that reasonably could have been raised in the IPR petition filed, even though the text of the statute applies estoppel only to grounds that “reasonably could have [been] raised during that inter partes review.” Apple would like to challenge the validity of Caltech’s patents, was barred by the District Court based upon Apple’s unsuccessful IPR against the same patent.

Bill Lee (Wilmer) is counsel of record for petitioner. Briefing is ongoing in the case.

6. Judicial Recusal in Centripetal Networks, Inc. v. Cisco Systems, Inc., No. 22-246 (Briefing ongoing)

Although a patent case, the focus here is about the judicial code. Cisco lost a $2 billion verdict, but was able to get the decision vacated on appeal because the Judge’s wife owned $5,000 in Cisco stock. The judge had placed it in a blind trust, but the appellate court found that was insufficient since the statute requires “divestment” under the statute. The petition asks whether this strict statutory interpretation is correct; and whether any impropriety can be excused as harmless error.

Former Solicitor Paul Clement is handling the petition.

7. Summary Judgment standard in Hyatt v. USPTO, No. 21-1526

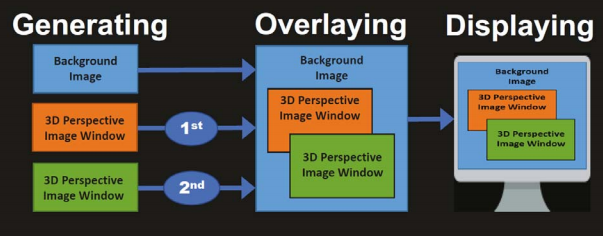

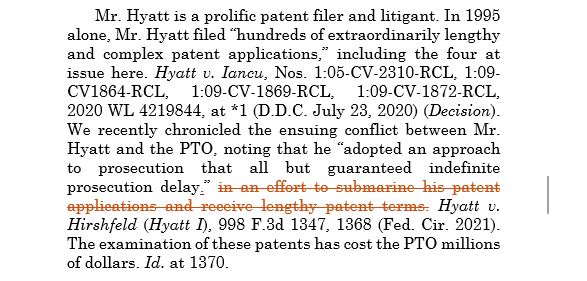

My favorite part of this litigation is the mock-up created by folks at the USPTO of Gil Hyatt applying the “Submarine Prosecution Chokehold.” Although the image was a ‘just a joke,’ Hyatt is not joking about what it represents. In particular, Hyatt argues that the USPTO created a secret policy to block issuance of his patents, regardless of the merits of his particular claims. Hyatt filed an APA lawsuit seeking an order forcing the PTO to actually examine his patent applications. But, the district court issued a sua sponte summary judgment — finding that the office was already diligently working. Oddly though, the court did not apply the summary judgment standard provided by R.56 but instead drew inferences against Hyatt. The petition asks simply: “Whether the ordinary summary judgment standard of Rule 56 applies to review of agency action.” Hyatt also argues that the district court applied too-high a standard with regard to setting aside past agency actions.

Famed professor of constitutional law Erwin Chemerinsky (Berkeley) filed the petition. The U.S. Gov’t waived its right to file a responsive brief.

8. Double Patenting and SawStop Holding LLC v. USPTO, No. 22-11

The petition here focuses on the non-statutory judicially created doctrine of obviousness type double patenting. It asks: “Is the judicially created doctrine of nonstatutory double patenting ultra vires?”

A good percentage of patents (about 10% or so) are tied to another patent via terminal disclaimer. In general, the patent office requires a terminal disclaimer in situations where a patentee is seeking to obtain a second (or subsequent) patent covering an obvious variation of an already obtained patent. Otherwise, the second patent will be rejected on grounds of obviousness-type double patenting. When I previously wrote about the case, I compared it to the Supreme Court’s abortion decision in Dobbs. In that case, the court explained that a right to abortion “is nowhere mentioned in the Constitution.” Similarly, obviousness type double patenting has no grounding in the Patent Act. Dobbs also rejected the 50 year old precedent of Roe v. Wade (1972). The fact that a precedent is old does not convert that precedent to a sacred text. One difference here is that OTDP has a somewhat older provenance than did Roe.

The need for terminal disclaimers was greatly reduced following the 1995-GATT patent term transformation. For the most part, all family members expire on about the same date. The big difference happens with patent-term-adjustment that can sometimes make a really big difference — especially if the patentee has successfully appealed. The SawStop situation represents an interesting case-study for anyone thinking about the ongoing importance of OTDP and Terminal Disclaimers.

David Fanning is inhouse counsel for SawStop and filed the petition. The USPTO (through the SG) waived its right to file in opposition.

9. Eligibility in Worlds Inc. v. Activision Blizzard Inc., No. 21-1554

Worlds was an early developer of 3-D virtual chatrooms and its US7,181,690 has a 1995 priority filing date. This particular patent has two steps to be performed on the client device being operated by a first user:

- (a) Receive position information about some user-avatars

- (b) Using that position information, determine which avatars to display to the first user

The courts found the claims directed to the abstract idea of “filtering.” The petition asks (1) what is the standard being “directed to” an abstract idea; (2) who bears the burden of coming forth with evidence on Alice Step 2. In particular, does a party seeking to invalidate a claim need to provide evidence of what was well-known, routine, and conventional? The petition here is really a follow-on to American Axle. That was denied certiorari at the end of the 2021-2022 term.

Wayne Helge (Davidson Berquist) is counsel of record for Worlds. Sonal Mehta (Wilmer) represents Activision, but only filed a statement waiving her client’s right to respond.

10. Mandamus Jurisdiction in CPC Patent Technologies PTY Ltd. v. Apple Inc., No. 22-38

This petition fascinated me for a couple of days as I tried to think through the scope of mandamus jurisdiction. We know that the Federal Circuit hears patent appeals, but the petition argues that the same court does not necessarily hear mandamus actions filed in patent cases. Rather, according to the petition, the Federal Circuit’s jurisdiction should depend upon whether the mandamus action itself arises under the patent laws. Here, the mandamus focused on transfer for inconvenient venue under Section 1404(a). Everyone agrees that issue is not patent law specific.

George Summerfield (K&L Gates) is handling the petition. Apple did not file a response.

11. Eligibility in Interactive Wearables, LLC v. Polar Electro Oy, No. 21-1281

This case has similar features to Worlds v. Activision and was also filed in prior to the denial of American Axle. The petition explains that the patents claim “electronics hardware device comprising a content player/remote-control combination having numerous concretely-recited components that undisputedly qualifies as a ‘machine’ or ‘manufacture’ under the statutory language of 35 U.S.C. § 101.”

12. Junker v. Medical Components, Inc., No. 22-26

Junker’s petition raises an issue that has repeatedly come before the court — the on sale bar. Here, the purported “offer to sell” was made by “a third party who had no right to sell the invention and with no involvement by the patentee?” Junker asks whether that counts as an offer?

13. Licensee Standing in Apple Inc. v. Qualcomm Incorporated, No. 21-1327

This petition raises the identical issue that Apple raised in a 21-746. That case was denied certiorari earlier in 2022 and is very likely to be denied here as well. The question presented: “Whether a licensee has Article III standing to challenge the validity of a patent covered by a license agreement that covers multiple patents.” Qualcomm restated the question as follows: “Whether a licensee that offers no evidence linking a patent’s invalidation to any concrete consequence for the licensee nevertheless has Article III standing to challenge the validity of the licensed patent.”

Mark Fleming (Wilmer) represents Apple and Jonathan Franklin (Norton Rose) represents Qualcomm.

14. Eligibility and Hardware in Tropp v. Travel Sentry, No. 22-22

This eligibility petition attempts to distinguish Alice on grounds of computer-technology vs real hardware with the following question presented: “Whether the claims at issue in Tropp’s patents reciting physical rather than computer-processing steps are patent-eligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101.” One issue with the petition is that the problematic claims don’t really claim the physical hardware (a padlock with a master key), but rather a process of giving the extra key to TSA. In some ways, I see this as a lower-quality version of American Axle.

15. PTO Acting Ultra Vires in CustomPlay, LLC v. Amazon.com, Inc., No. 21-1527

Anyone working with inter partes reviews (IPRs) knows that the PTAB first decides whether to institute the IPR and, after instituting, will hold the trial and issue a final written decision. One oddity though is that the statute actually calls for the USPTO Director to decide the institution question with the PTAB only stepping in once the IPR is instituted. The current procedure exists because the PTO Director has delegated her institution authority to the PTAB. In its petition, CustomPlay asks the court to rule that this delegation is improper – a violation of “the statutory text and legislative intent.” In addition, the petition asks a constitutional due process question: “Whether the PTO’s administration of IPR proceedings violates a patent owner’s constitutional right to due process by having the same decisionmaker, the PTAB, render both the institution decision and the final decision.”

16. Filler v. United States, No. 22-53

Filler had an interesting claim, but made a major error by dividing his patent rights between two entities in such a way that neither had enforcement power. Filler argues that the U.S. Gov’t used his patented invention without paying and sued in the Court of Federal Claims. The petition here asks about whether his Fifth Amendment takings claim was properly barred by the Assignment of Claims Act.

Filler is the inventor and is also an attorney (and MD and PhD) filed the petition himself.

17. Arunachalam v. Kronos Incorporated, No. 22-133

Lakshmi Arunachalam has filed a number of patent related petitions over the past several years. This one asks a number of questions including “Whether Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U.S. 518 (1819) was properly decided.”