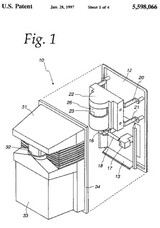

DESA owns a patent directed to motion-activated security lights. The lights have a low-level always-on illumination as well as a bright security illumination that is activated when motion is detected by a passive infrared motion sensor. During infringement litigation, the district court construed the claims and consequently entered a stipulated judgment of noninfringement.

The appeal focused on whether the disputed claim phrases — “sensor means,” “control circuit means,” and “switching means” — should be interpreted as means-plus-function.

The use of the word “means” in the claim language invokes a rebuttable presumption that § 112, ¶ 6 applies; conversely, the failure to use “means” invokes a presumption that § 112, ¶ 6 does not apply. . . . Nonetheless, the presumption that § 112, ¶ 6 applies may be rebutted if the claim recites no function or recites sufficient structure for performing that function.

Distinguishing earlier precedent, the CAFC determined that neither the sensor, control circuit, nor switching pre-means terms recited sufficient structure.

DESA argues that this court has previously stated that “it is clear that the term ‘circuit’ by itself connotes some structure.” In Apex, however, the word “means” was not used, so the reverse presumption—i.e., that § 112, ¶ 6 does not apply—was invoked.

Regarding interpretation of the claims, the CAFC found that the district court had improperly given the terms a narrow construction by focusing on the preferred embodiments and the figures.

David (and others),

Cole v. Kimberly-Clark Corp. definitely does not support that proposition. the “perforation means” limitation had more language than just “performation means.” It also included other structural requirements (i.e. where the perforation means were located, and the fact that they had to extend all the way through a particular claimed layer). Similarly, in Allen Eng’g, “gearbox means” further defined that term to require “a pair of rotatable shafts projecting downwardly from said frame means” and the “flexible drive shaft means” further required “individual shaft sections axially linked together by friction disk means.”

I haven’t looked at the other two cases you cite, but my guess is there was more than just “____ means for [performing function],” i.e. “wherein said ____ means comprises a widget connected to said first doohickey.”

P.A. asks “Can anyone cite a case where the claim language was ‘____ means’, and the ‘____’ word was used to rebut the MPF presumption?”

How about Cole v. Kimberly-Clark Corp., 102 F.3d 524 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (“perforation means”)?

See also:

Envirco Corp. v. Clestra Cleanroom, Inc., 209 F.3d 1360, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2000) (“second baffle means”)

Turbocare v. General Electric, 264 F.3d 1111 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (“compressed spring means”)

Allen Engineering v. Bartell Indus., 299 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (“seat means for . . . ,” “motor means for . . . ,” “gearbox means for . . . “, etc.)

Anthony: I’m not an EE. Are you saying that one skilled in the EE arts could not determine whether a component was a circuit or not?

The quick answer is that if term, such as circuit, does not have a generally understood structural meaning in the art and if the language following is purely functional, then 112p6 is not avoided. The term “circuit” does not have a generally understood structural meaning compared to say a term like amplifier or comparator or decimator. The term “circuit” is completely devoid of any structure in the EE arts. The term circuit is so generic as to not have any structure.

See Mass Hamilton v. LaGard. Specifically, the issue is whether the term “circuit” and not the language following has sufficient structure. As was stated in Greenberg “what is important is not simply that the element at issue is defined in terms of what it does, but that the term, as the name for a structure, has a reasonably well understood meaning in the art.”

I do not think that the term “circuit” alone has a well understood meaning in the art. The term is not a term such as I have mentioned above that conveys structure.

I know of several cases where the court has held that circuit does have sufficient structure, but I think these cases are wrong on this point. They have imported meaning into the term “circuit” from the function, rather than focusing on the term itself. That, I believe, is an error.

Why isn’t “circuit” sufficient structure? Can’t a circuit perform the recited function?

Yes, Luke is on the right track here. The term “circuit,” without the presumption, connotes sufficient structure. “Circuit means,” with the presumption, somehow does not. How is it that the recitation of one word changes “circuit” from having sufficient structure to not having sufficient structure? Why is not the recitation of “circuit” in “circuit means” sufficient to rebut the presumption of 112 p.6, if “circuit” has sufficient structure to avoid 112 p.6?

I say that neither “circuit” nor “circuit means” has sufficient structure if what follows is the recitation of a function of the circuit. Circuit is just as much a generic term as mechanism (in a mechanical setting).

Let me get this straight. “Circuit” when there is a presumptuion that MPF does not apply sufficiently defines a structure. “Circuit” when there is a presumption that MPF applies does not sufficiently define a structure. Circuit = Circuit. Not in the Federal Circuit.

Mr. Cohen, I think it’s interesting for 2 reasons: (1) mpf claims are complicated, and any time the CAFC examines one it’s somewhat mentionworthy, and (2) the CAFC reversed the district court’s claim construction in this case. After Amgen, the statement at p. 7 that “[a]lthough the

district court seemed to rely upon expert testimony, we note that its

conclusion could have been reached without the aid of extrinsic evidence,” is kind of interesting.

“Has anyone had success convincing a district court that an overly generic term, which is given too broad of a proposed construction by a patentee, should be given MPF treatment?”

Mark, see MIT v Abacus Software: “We agree with the district court’s conclusion that the presumption here is overcome and that the phrase “colorant selection mechanism” should be construed as a means-plus-function limitation. The generic terms “mechanism,” “means,” “element,” and “device,” typically do not connote sufficiently definite structure.”

link to fedcir.gov

Has anyone had success convincing a district court that an overly generic term, which is given too broad of a proposed construction by a patentee, should be given MPF treatment?

Obviously patentees always want the broadest construction possible, but where is the line drawn, such that when a patentee goes too far, they genericize their claim terms to the point that their specification should specifically define the structure as described, not necessarily as claimed?

Is this case even worth a mention?

Apex, and to a further extent MIT v Abacus, held that the claim term “circuit” connotes structure, avoiding MPF treatment.

This case dealt with “circuit means”, and presence of the word “means” always raises a presumption of MPF treatment. Putting circuit, or any other word for that matter, in front of “means” doesn’t provide enough structure to rebut the presmuption. Typically, the only way to rebut the presumption is to describe the structure after “means”, such as “means for securing part A to part B, said means comprising a nail.”

The conclusion in this case is quite unremarkable.

Can anyone cite a case where the claim language was “____ means”, and the “____” word was used to rebut the MPF presumption?

Yes. Distinguish does not mean overrule — Rather, it means that the court finds some reason why the facts of this case are different-enough to warrant an different outcome

Can a nonprecedential opinion distinguish precedent?

Comments are closed.