(J.Lourie) IVAX’s infringement began when it filed an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) with the FDA for approval to manufacture a generic version of Forest Lab’s blockbuster antidepressant Lexapro. Under 35 USC 271(e)(2), the mere submission of the ANDA is considered an “act of infringement.”

At the conclusion of the case, the district court issued an injunction ordering IVAX to refrain from making or using “any products” that infringe Forest’s patent. CIPLA, IVAX’s planned distributor, was also included in the injunction.

IVAX and CIPLA both appealed the injunctions.

Overbroad Injunction: An injunction may only extend to adjudicated products (or methods) and those “not more than colorably different.” In this case, the CAFC found that the injunction language was overbroad because it applied to “any products” that infringe the patent. The court consequently modified the injunction to specifically focus on the products at issue. (Note: Under 271(e)(4), the court may issue injunctive relief to prevent the future manufacture and sale of the infringing product).

Injunction against CIPLA for Potential Contributory Infringement: IVAX is a direct infringer based on its ANDA submission. CIPLA, on the other hand, made no such submission and is not a direct infringer. Likewise, CIPLA is not a contributory infringer based on the ANDA submission. As the majority noted – “Ivax is not currently liable for infringement, as long as it is only pursuing FDA approval.”

Despite any current infringement, the Appellate Panel found that it is proper to issue an injunction to prevent potential future contributory infringement.

“[If the drug were sold] CIPLA would be contributing to the infringement by IVAX, so the injunction should cover both partners.”

Judge Shall dissented – arguing that CIPLA should not suffer under an injunction.

Notes:

-

Double Standard: The majority found that an injunction is overbroad if it includes non-adjudicated products, but that an injunction is not overbroad if it includes prohibitions against a non-adjudicated party.

- Where are those Principles of Equity: Interestingly, the injunction portion of the decision did not discuss the Supreme Court’s recent case of eBay v. MercExchange. EBay focused on the language of the statute typically associated with patent infringement injunctive relief – 35 USC 283. Here, the law supporting the IVAX injunction is found at 35 USC 271(e)(4). There are some differences between those two statutes, although both are written in the permissive form – that courts “may” grant injunctions or injunctive relief. It is clear that the traditional equitable relief test should apply to Section 283 injunctions since the statute calls for use of “the principles of equity.” Another difference is that no money damages are available for Section 271(e) infringement. Are those differences sufficient enough to allow the court to issue an injunction under 271(e)(4) without considering the principles of equity required by the Supreme Court in EBay?

It all depends on what is being claimed.

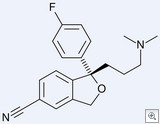

In this case, what is claimed is a substantially pure form of an enantiomer. Prior art did not anticipate it (for lack of enablement). The decision on validity is correct.

I’m not a Chem Guy but I had always understood that, at least in Europe, there was nothing controversial about the established proposition that the “new” chemical entity, as such, is prima facie obvious. To get a valid claim to the molecule as such, you need something more than bare novelty. The English courts are fond of stressing that novelty is no defence against obviousness attacks. So, Warren, maybe you want to re-think whether you should acquaint your clients with this basic truth?

“Chemical entities in themselves are not inventive.”

wow. do you tell your pharmaceutical clients that?

I think the injunction against CIPLA is unfair. Couldn’t it include every drug maker in the world? Any of them could be contributory infringers at some time in the future.

Dennis:

The eBay case hinged, in my view, on the difference in the statute between damages and an injunction. The patentee was entitled to damages but the court had discretion (“may”) when issuing an injunction. eBay stands for the proposition that Congress did not authorize “automatic” injunctions in patent cases, which was the de facto norm before the CAFC.

Here, Congress DID expressly provide the injunction as THE remedy for infringement under 271(e)(2). So I think the case is distinguishable from eBay.

Hope things are well in Missouri.

“I would have to disagree with you there, ChemPatGuy. If you can come up with an arbitrary crazy chemical without any means to make it, there is no chance you would get a patent because it would not be enabled.”

Tufty, you writhe like a snake to avoid my righteousness. I did not say that by dreaming up the crazy chemical without a way to make it that I was entitled to a patent on it (but you’re right, I’m not) – I said that I was not entitled to invalidate future patents on the crazy chemical (patents owned by the guy who figures out how to make the crazy chemical).

Metoo,

Most of what you said is true, but utility has a much lower bar in the predictable arts. The Applicant can define the utility any way they want, even if the end result is not useful. For example, I could claim a macramé bathtub. Not actually useful, but patentable under 101.

I believe in the chemical arts, some level of actual usefulness is required to meet the 101 utility bar.

“Chemical entities in themselves are not inventive.”

Huh??? Are you suggesting that every chemical entity ever “invented” already existed in nature? Cuz that sure is hell not correct. New chemical entities are actually invented, i.e., created, by scientists all the time. Now, if you are suggesting that the inventive process is not complete until some utility is established, that is correct. Of course that’s true for any invention. For example, one cannot connect a bunch of electrical components to one another in some random fashion and declare it an “invention.” In order to complete the inventive process (particularly in the patentable sense), the electronic concoction must have some use.

The only difference, perhaps, is that in the chemical and pharmaceutical area, the inventive process can be somewhat reversed when compared to other scientific fields. Thus, the inventive process for chemicals and pharmaceuticals might start with the synthesis of a new chemical entity, and end with the “discovery” of the utility for that new entity. (Although in most cases the inventor has an utility in mind when the new entity is created)

“So, I already know the invention and any further inventive step to a chemical entity is a matter of, at best, tossing a coin.”

That’s false. You’d have to figure out how to purify it. And it may be the case that a mixture of enantiomers provides synergistic beneficial effects that aren’t provided by each of the enantiomers alone. Such are the conundrums confronted by those who practice in the “unpredictable arts.”

I would have to disagree with you there, ChemPatGuy. If you can come up with an arbitrary crazy chemical without any means to make it, there is no chance you would get a patent because it would not be enabled. However, that misses the whole point of why patents get granted for chemical entities. Chemical entities in themselves are not inventive. The invention (essentially a legal fiction) lies in the scientific discovery of the chemical having certain properties, e.g. a cure for cancer. Enablement is a different issue.

If I knew that a racemic mixture had certain properties relating to a disease, I would know for sure that one of the enantiomers would work better than the other, so I would get on with finding out how to separate them. So, I already know the invention and any further inventive step to a chemical entity is a matter of, at best, tossing a coin. I know that the standard of obviousness in the US is considerably lower than the rest of the world, but this decision is taking things a bit far.

So, who are you gonna believe, the CAFC en banc or the Supremes?

Incidentally, Phillips, e.g., cited on page 7 of today’s Gillespie v Dywidag decision, does not wash with the Supremes’ eBay debacle! Page 7’s Phillips citation:

See Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1312 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc) (“It is a ‘bedrock principle’ of patent law that ‘the claims of a patent define the invention to which the patentee is entitled the right to exclude.’”).

Luke, your argument only holds if the claim was to the enantiomer. In this case, the claim was to the substantially pure enantiomer. Big difference, and the one that allows the claim to stand. Your point is supported by case law if the claim was only to the enantiomer.

Dennis, I think you are reading Ebay too mechanically. You, yourself, mentioned that damages are unavailable here. Effectively, then, there are no other possible remedies avaiable other than an injunction.

By proposing that all traditional factors of equitable relief must be considered in this case, you are basically suggesting that a legal wrong (patent infringement) may not be legally remedied! That position is simply absurd! Legal wrongs always have a legal remedy.

RE EBay: It is certainly less work for the judges and parties if courts do not need to consider the traditional factors of equitable relief. My point here is that the Supreme Court has ordered that equitable factors must be examined before issuing an injunction for patent infringement.

I’m with ChemPatGuy. Who cares if the racemic mixture was known? The claim is to a substantially pure enantiomer – something that had never existed before and, on the basis of the significant effort that went into finding a way to actually make it, was in this case definitely not obvious. There may be times when it’s trivial to do an enantiomeric separation, but this wasn’t one of them. Heck, they didn’t separate a racemic mixture of the active, they did the separation upstream and completed the synthesis on the separated precursor (under conditions that could well have led to racemization).

As to the question of issuing an injunction at all: Dennis, under ANDA litigation, an injunction is the only available remedy. Are you saying that in the wake of Ebay, generic drug companies should be able to infringe at will, i.e. why should they be different than any other infringer? What you seem to be proposing is that notwithstanding the finding of infringement during ANDA litigation, the generic guys should be allowed to import, thus necessitating a new trial in which damages can be assessed. How is that more efficient than issuing an injunction that prevents infringement from taking place? Is that a good use of the courts’ (and the litigants’) time?

@chempatguy: It seems that your example is not on point since the racemic mixture can be made. If the racemic mixture is known then it should not be possible to claim one enantiomer even if you can’t make one enatiomer without the other. You should on the other hand be able to claim a method of making the single enantiomer if it is new and nonobvious.

Your example only refers to compounds you could dream up but that don’t exist or can’t be found.

Tufty, a chemical composition may not be obvious if there is no obvious way of making the compound. This rule is ancient. See In re Hoeksema, 399 F.2d 269, 274-75.

Thus, I can dream up any absurd chemical compound and even draw its chemical diagram, but if I can’t make it, I haven’t rendered it obvious. This rule seems correct, yes? I dream up the idea of a machine that turns lead into gold, but I can’t make the machine, so the machine isn’t made obvious by my idea of the machine. Simply because chemical formulae are more precise and easily generated doesn’t make a difference.

The decision on validity is clearly wrong. If the idea of the single enantiomer was obvious, given that the racemic mixture was known, then it should not be possible to claim the enantionmer by itself, regardless of whether it was possible before the priority date to make it. The actual invention in this case lay in how to separate the enantiomers, not the idea of which one would be better. The patentee should therefore have only been allowed a method claim on how to do it. The corresponding decision in the UK got it right (see link to ipkitten.blogspot.com).

Comments are closed.