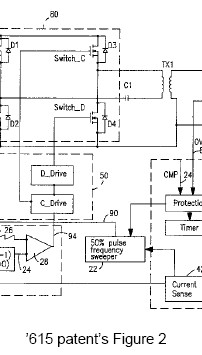

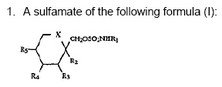

A jury found O2 Micro’s DC/AC converter patents willfully infringed and not invalid. The Eastern District of Texas court (Judge Ward) then issued a permanent injunction.

Waiver of Claim Construction Appeal: During a Markman hearing, the parties sparred over the definition of the term “ONLY IF”. Rather than issuing a claim construction decision, the district court decided that the common phrase needed no explanatory construction. After having lost to the jury, the defendants appealed the lower court’s failure to construe the ONLY IF phrase. However, because the defendants did not specifically object to the jury instructions, O2 Micro argued that the the defendants has waived their right to appeal.

The issue of waiver of claim construction has been raised before, and the CAFC dismissed it again — this time by quoting the CAFC’s own 2004 Cardiac Pacemakers opinion:

“When the claim construction is resolved pre-trial, and the patentee presented the same position in the Markman proceeding as is now pressed, a further objection to the district court’s pre-trial ruling may indeed have been not only futile but unnecessary.”

Thus, if disputed at a Markman hearing, claim construction appeal issues are not waived by failure to object to jury instructions. Furthermore, the CAFC will also allow new arguments to be presented on appeal justifying the previously proposed construction.

Construing all the terms: Although the meaning of the phrase “ONLY IF” was disputed by the parties, the district court failed to construe the term. In its decision, the CAFC vacated — finding that the disputed phrase should have been construed. By failing to define the term, the court essentially passed the construction dispute to the jury.

“When the parties raise an actual dispute regarding the proper scope of these claims, the court, not the jury, must resolve that dispute. . . . When the parties present a fundamental dispute regarding the scope of a claim term, it is the court’s duty to resolve it.”

In deciding this issue, the CAFC indicated that claim construction requires determining both the meaning of the words in the claim and the scope encompassed by the claim. Further, even ordinary terms need construed when they are susceptible to multiple interpretations.

Overburdening: Over the past decade, the number of terms being construed (and appealed) has risen dramatically. In its decision, the CAFC at least waived its hands at the problem — recognizing “that district courts are not (and should not be) required to construe every limitation present in a patent’s asserted claims.” (Emphasis in original). No, the court only needs to construe those claim terms that are disputed, subject to alternative theories, that could be helped by clarification, and when otherwise necessary to describe the claim coverage.

Meaning and Scope: This case is quite important because it shifts even more power and importance onto the issue of claim construction and away from a jury’s factual determination of infringement and novelty.

Akira Akazawa v. Link New Tech (

Akira Akazawa v. Link New Tech ( Saint-Gobain Calmer, Inc. (now MeadWestvaco Calmer) v. Arminak & Associates, Inc. (on petition for certiorari 2008)

Saint-Gobain Calmer, Inc. (now MeadWestvaco Calmer) v. Arminak & Associates, Inc. (on petition for certiorari 2008) Microsoft Corp. v. z4 Tech. (on petition for certiorari 2008)

Microsoft Corp. v. z4 Tech. (on petition for certiorari 2008) Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical v. Mylan Labs (

Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical v. Mylan Labs (