Jack Frolow v. Wilson Sporting Goods (Fed. Cir. 2013)

The decision here focuses on the evidentiary value associated with the fact that a patent licensee marked its products as patented but then later claimed that the same products are not covered by the listed patent. After the break, I also discuss the arising-under jurisdictional issue raised by the situation but not challenged by the court.

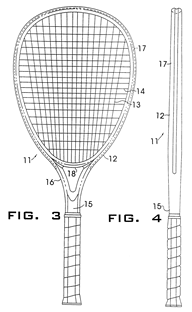

Background: Frolow's patent covers a tennis racket with a particular moment-of-inertia and center of percussion. U.S. Patent Reissue No. Re 33,372. Wilson licensed the original patent back in 1989 but Frolow later sued – alleging breach of contract and patent infringement based upon Frolow's test that showed 42 Wilson rackets were covered by the patent but that were not subject of royalty payments. The district court partially dismissed the case on FRCP Rule 56 summary judgment – holding that Frolow had failed to present material facts sufficient to create a genuine dispute as to whether 37 of the rackets were covered by the patent and/or license. At trial, the district court then granted Wilson's FRCP Rule 50 judgment as a matter of law – holding that the patentee had failed to present sufficient evidence that the remaining five rackets fell within the scope of the patent. On appeal, the Federal Circuit has reversed the summary judgment holding.

Three Judges Four Decisions: The decision structure here is odd to say the least. All three judges agreed on the outcome but were still able to produce four separate opinions. The majority opinion is written by Judge Moore and signed by Judge Clevenger. Judge Moore and Clevenger each provided their own separate opinions with "additional views." And, Judge Newman filed a concurring opinion that agreed with the final judgment.

Here, Wilson had marked all of its rackets as patented and listed the Frolow patent number on each. Frolow asked the court to apply a doctrine of "marking estoppel" to prevent Wilson from later arguing that the products are not covered by the patent. The appellate court refused to adopt the doctrine of marking estoppel, but did find that Wilson's marking should serve as factual evidence of extra-judicial admission tending to prove infringement. In the process, the appellate court rejected the lower court's ruling that the marking was irrelevant to infringement analysis.

Placing a patent number on a product is an admission by the marking party that the marked product falls within the scope of the patent claims. The act of marking is akin to a corporate officer admitting in a letter or at a deposition that the company's product infringes a patent. A defendant, of course, is free to introduce counter evidence or explanation. Thus, the district court erred when it concluded that Wilson's marking had "no bearing on whether literal or doctrine of equivalents infringement has occurred."

Like any other type of extrajudicial admission, evidence of marking is relevant evidence. And such an admission, that the accused product falls within the asserted claims, is certainly relevant on the issue of infringement. Of course, whether a party's marking, in view of the record as a whole, raises a genuine issue of material fact, will depend on the facts of each case. . . . .

On remand, a new jury may be finally asked to decide the infringement question.

In her concurring opinion, Judge Newman suggested that the marking by Wilson should create a presumption of infringement rather than simply circumstantial evidence of infringement. That would place the burden on Wilson to disprove infringement in a manner akin to the rule created in Medtronic v. Boston Scientific, 695 F.3d 1266 (Fed. Cir. 2012). In that case, the court ruled that a licensee in good standing who files a declaratory judgment lawsuit challenging the patent has the burden of proving non-infringement. The Medtronic case is now pending before the Supreme Court on petition for writ of certiorari.

The additional separate opinions by Judges Clevenger and Moore focused on the potential unfair prejudice associated with telling the jury that Wilson had marked its rackets as covered by Frolow's patent. For Clevenger argued that evidence should probably be excluded under Fed. R. Evid. 403 because of the danger of unfair prejudice that outweighs the evidentiary value. Judge Moore disagreed.

= = = = =

Arising Under Jurisdiction?

One oddity about the case is that the patent claim was dismissed early on for failure to state a claim. In particular, Frolow admitted in the complaint that Wilson had a license and that the only problem was Wilson's failure to pay the required royalty amount. Based on meritless allegations, the court dismissed the patent claim. See Vulcan Engineering Co., Inc. v. Fata Aluminum, Inc., 278 F.3d 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2002); Cyrix Corp. v. Intel Corp., 77 F.3d 1381 (Fed. Cir. 1996); United States v. Studiengesellschaft Kohle m.b.H., 670 F.2d 1122 (Fed. Cir. 1981) ("The license waives this right to judicial relief against what, but for the license, would be an infringement."); Schering Corp. v. Zeneca, Inc., 958 F. Supp. 196 (D. Del. 1996) ("Zeneca's license provides an absolute immunity from Schering's infringement action," citing DeForest Radio Telephone and Telegraph Co. v. United States, 273 U.S. 236 (1927)).

After dismissing the patent claim, the district court was left only with the contract dispute. Certainly, that aspect of the case still involved lots of patent issues. Since the scope of licensed products was contractually defined as products that fall under the patent, the court had to figure out which rackets are "infringing" in order to know which ones are covered by the license. However, we know now (under Gunn v. Minton) that the contract claim probably does not arise under federal patent law. The absence of the patent issues was not a problem for the district court here, since there was also diversity jurisdiction. However, the jurisdictional basis is important for knowing whether the appeal goes to the Federal Circuit or to the regional circuit court of appeals. Only cases arising under the patent laws are appealed to the CAFC.

The question in my mind is whether this case arose under the patent laws. In Hunter Douglas v. Harmonic Design, 153 F.3d 1318 (Fed. Cir. 1998), the Federal Circuit found a distinction between claims cases dismissed for lack of subject matter jurisdiction under FRCP R. 12(b)(1) and claims dismissed for failure to state a claim under FRCP R. 12(b)(6). According to the court, 12(b)(1) dismissal indicates a lack of arising under jurisdiction while a claimed dismissed on 12(b)(6) can still be said to have arising under jurisdiction. This creates a difficult to comprehend result because we may result in a situation where the well pleaded complaint is considered to include a federal patent claim even though the court dissmisses that same claim for on 12(b)(6) for failure to state a claim in the pleadings.

The catchphrase of the Hunter Douglas decision by Judge Clevenger is whether the federal claim being stated is "wholly insubstantial." Other courts similarly look to see whether the federal claim is a "frivolous" federal claim. If the federal claim meets either of these tests then it is said to arise under federal law even if the court later dismisses that claim.

The question that the appellate court failed to address here is whether it had appellate jurisdiction and, that question will turn on wether the original patent claim was frivolous or wholly insubstantial. Because jurisdictional questions are generally not waivable, Wilson could immediately file for reconsideration based upon the court's lack of appellate jurisdiction. This also makes sense because the Gunn decision was released well after briefing and oral arguments were complete.

One question, does the contract case raise a substantial question of patent law such that it is Gunn-approved under 1338 without the infringement claim? Second question, if it does not, does supplemental (or pendant for those of us who went to law school a long time ago) jurisdiction carry it up to the Federal Circuit anyway despite the infringement claim being dismissed on the merits?

The Federal Circuit would say yes to the first (which explains why it doesn’t ask about the second), based on US Valves and a handful of other cases where it accepts determining what products would be infringed as a patent question in contract cases. (I happen to think that is not quite correct based on other arising under law, but I’m not on the Federal Circuit, and what I think Dennis is hinting at is that Gunn could/should change that…)

As to the second question, I have no idea and would be interested in the answer from a federal courts person.

The district court wouldn’t care about either issue because it has diversity jurisdiction. It would be up to the winning party to challenge the loser’s appeal to the Federal Circuit, or the Federal Circuit to kick the case back out to a regional circuit on its own. If I were the parties here, I might prefer the Federal Circuit because it’s a simple contracts case: construe claims and compare to products, hold the licensee owes contract royalties on the ones that are infringed and nothing on the ones that are not.

Mr. Holmes, not, isn't the real question whether there's any remaining jurisdiction to hear the contract dispute after the patent dispute is no longer in the case?

Sent from Windows Mail

You may be confusing merits and jurisdiction. I believe (and I would love to hear if I’m wrong) that arising under jurisdiction arises with the complaint (the well-pleaded complaint rule and all) and if the claim is soon dismissed on the merits (FRCP 12b6) that does not later render the case not a patent one. The complaint here (from the patent owner) is one for breach of contract *and* infringement, which would arise under the patent laws per 28 USC 1338 even if the patent owner turns out to lose the infringement claim on the merits. (I admit that the difference between 12b1 and 12b6 in this license context is practically indistinguishable.)

Not sure about whether this affects CAFC jurisdiction, though, as it is tied to 1338 through 28 USC 1295… Thoughts?

Dennis, good thinking on the jurisdictional issue.

Clevenger is taken to the woodshed by Moore.

You would think that the judges would discuss this in private, and come to some united front rather than air this type of dirty laundry.

What was Clevenger thinking?

Comments are closed.