by Dennis Crouch

Roku’s recently filed en banc petition begins with an intriguing statement: “What should have been a garden-variety substantial-evidence appeal has produced a dangerous obviousness precedent—one as far-reaching as it is misguided.” [Roku, Inc. v. Universal Electronics, Inc., Docket No. 22-01058 (Fed. Cir.) (en banc petition)]

An every day part of patent practice is arguing about whether a cited prior art reference teaches a particular claim limitation. That analysis is not always an easy task because prior art is often quite cryptic as are the patent claims being evaluated. One way to look at the process is an interpreting of the prior art to see if it teaches the claim. In that form, the process is seen a question of fact that must be based upon substantial evidence and reviewed with deference on appeal. Tribunals also often use an alternative approach that involves a question of law reviewed de novo on appeal. In the alternative approach, the patent claim is interpreted to see whether it covers the the prior art in the process known as claim construction. The difference between these two approaches is subtle, but often with huge results.

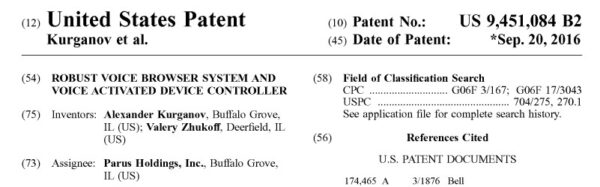

In its recent Roku decision, the Federal Circuit provides an example of these two approaches. Roku, Inc. v. Universal Electronics, 63 F.4th 1319 (Fed. Cir. 2023). The 2-1 majority decided to interpret the prior art to see whether it taught the claimed multiple “communication methods.” The court found value in “both sides of this factual question,” but ultimately gave deference to the Board’s conclusions. In her dissenting opinion, Judge Newman contended that the majority overlooked the established principle that the obviousness is a question of law that should be reviewed afresh, or ‘de novo’.

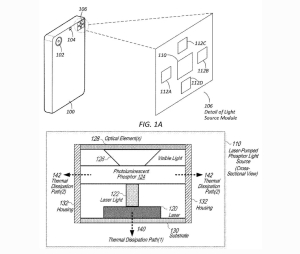

Universal Remote: In its IPR petition, Roku presented the prior art (“Chardon”) that described a universal remote control that uses two different types of communications codes (CEC and IR) in order to control various devices. Chardon includes a table with CEC and IR codes for each different type of action that might be needed. The patent at issue claims the use of “two different communication methods.” The panel majority endorsed the Board’s factual finding that a “listing of command codes does not teach or suggest a listing of communication methods.”

In its rehearing petition, Roku argues that the panel majority’s analysis conflicts the Supreme Court’s repeated statement that obviousness is a question of law. Rather, according to Roku, the majority’s treatment of obviousness as effectively a question of fact contravenes 150 years of precedent holding that obviousness is a question of law. This shift could have far-reaching “pernicious consequences.”

Roku’s bad-consequences argument centers on two main points. First, they assert that the majority’s approach could undermine the uniformity of obviousness jurisprudence. I.e., the Court is effectively deferring to lower tribunals on the question of obviousness. This, they contend, contradicts a key purpose of the Court’s exclusive patent jurisdiction, which is to ensure nationwide uniformity in patent law. It also undermines the requirement set out in KSR that the obviousness analysis must be made explicit.

Second, Roku suggests that the majority’s methodology could lead to undesirable substantive outcomes — allowing for patents on trivial distinctions from the prior art. Roku argues that such trivial advances should not warrant patent protection as they do not represent real innovation and can hinder progress. They also caution that the majority’s approach could lead to genuine inventions being deemed unpatentable if the Court simply affirms factual findings without conducting a de novo analysis of obviousness. The argument here is that the appellate court is in a better position to judge obviousness than the PTAB or a Jury.

by Dennis Crouch

by Dennis Crouch