By Jason Rantanen

Crown Packaging Technology, Inc. v. Ball Metal Beverage Container Corporation (Fed. Cir. 2011) Download 10-1020

Panel: Newman, Dyk (dissent), Whyte (author)

For the past decade, the Federal Circuit has struggled to reconcile the the written description rules announced in its biotechnology-related opinions with the patentability requirements for patents in other technological fields. Particularly challenging for the court are the implications of a strong written description doctrine for mechanical inventions, which historically were subject to little scrutiny under the broad approach to the written description requirement.

Crown Packaging presents the latest iteration of the court's thinking on this issue. Penned by the highly regarded Judge Ronald M. Whyte of the Northern District of California, the opinion firmly lays to rest one possible argument for challenging mechanical patents on written description ground and confirms that the Problem-Solution approach to analyzing written description issues applied in Revolution Eyewear is alive and well post-Ariad. Given the depth of its treatment of the issue, this is an opinion that should go into every attorney's toolbag for addressing non-biotech related written description issues.

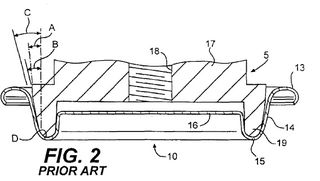

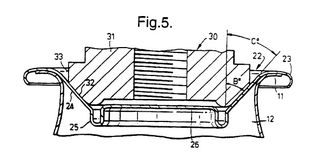

The patents at issue in Crown disclose a beverage can end that reduces the amount of metal wasted during the process of seaming the can end to the can body. (Picture a can of soda. The can end is the top portion that one drinks from. The can body is the part that contains the beverage.) The patents (which share a specification) solve the problem of reducing metal waste in two ways: first, by changing the angle of the vertical portion of the inside wall from nearly perpendicular to significantly angled, and second, by reducing width of the reinforcing bead (the little channel that runs along the inside of the can lip that tends to fill up with soda). Because simply reducing the width of the reinforcing bead can present structural challenges and result in unsightly scuffing, the patent also discloses a particular type of chuck (the portion of the seaming machinery that sits inside the top of the can against which the lip is rolled) that does not drive deeply into the reinforcing bead.

Figure 2 illustrates the prior art; Figure 5 is an embodiment of the invention. In the prior art can end, the peripheral walls are nearly vertical and the chuck (element 17) fully enters the reinforcing bead (element 15); in the embodiment of the invention, the walls are closer to 45 degrees and the chuck (element 31) does not enter the reinforcing bead (element 25).

Crown's two patents, one for a product and the other a method of manufacturing, include claims covering just the use of an angled wall without mentioning the narrow bead or penetration of the chuck. During the district court proceedings, Ball argued that these claims lacked written description support because they covered embodiments both in which the chuck was driven inside the reinforcing channel as well as embodiments in which the chuck was driven outside the bead despite only describing embodiments showing the latter in the specification. The district court agreed with Bell, granting summary judgment of invalidity.

Judge Whyte and Judge Newman disagreed with the district court. After dismissing the species-genus approach to these types of situations, the majority framed the issue in problem-solution terms. Relying on Revolution Eyeware, Inc. v. Aspex Eyewear, Inc., 563 F.3d 1358 (Fed. Cir. 2009), the court agreed with Crown that "[i]nventors can frame their claims to address one problem or several, and the written description requirement will be satisfied as to each claim as long as the description conveys that the inventor was in possession of the invention recited in the claim." Slip Op. at 13, quoting Revolution Eyewear at 1367. Here, there were two separate, clearly described solutions to the problem of improving metal useage: modifying the slope of the wall or limiting the width of the reinforcing bead. Nor does it matter that both solutions relate to the same problem: "we specifically held in Revolution Eyewear that it is a 'false premise that if the problems addressed by the invention are related, then a claim addressing only one of the problems is invalid for lack of sufficient written description." Slip. Op. at 14, quoting Revolution Eyewear at 1367. And the majority distinguished the issue of enablement from that of written description, concluding that Ball's argument relating to whether one of ordinary skill in the art could not seam a can with an increased sloped chuck wall without also avoiding contact with the reinforcing bead presented an issue of enablement, not written description.

One possible limitation on the majority's holding, however, is where the specification mandates that the prior art problems must always be solved together. Here, the specification did not so require – rather, "the specification supports the asserted claims that achieve metal savings by varying the slope of the chuck wall alone." Slip Op. at 15. Yet this will likely be an argument raised by future parties.

The Dissent

Although agreeing with the majority on the reversal of the district court's grant of summary judgment of anticipation, Judge Dyk disagreed with its treatment of the written description issue. Judge Dyk's dissent rested on a different reading of Revolution:

Relying on Revolution Eyewear, the majority holds that the claims are valid. However, Revolution Eyewear, in holding that a claim may address only one of the purposes disclosed in the specification, still requires explicit disclosure of the embodiments in the claims: “Inventors can frame their claims to address one problem or several, and the written description requirement will be satisfied as to each claim as long as the description conveys that the inventor was in possession of the invention recited in that claim.” Revolution Eyewear, Inc. v. Aspex Eyewear, Inc., 563 F.3d 1358, 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (emphasis added). Therefore, the claims, whether directed to solving a single problem or multiple problems, must still be grounded in the specification.

Thus in Judge Dyk's view, the claims lack written description:

There is no question that the specification does not teach combining the sloped can end wall together with the wider, prior art bead and driving the chuck into the bead instead of the sloped can end wall. That combination is a new and distinct invention, and our written description jurisprudence requires that it be described in the specification. The fact that the claims are broad enough to cover such an invention or imply that the claims cover such an invention is not sufficient when the invention itself is not described either in the claims or elsewhere in the specification. The failure of the specification to describe the invention requires invalidation of claims 50 and 52.

Commentary:

I find it difficult to agree with Judge Dyk's distinguishing of Revolution Eyewear, which was decided on strikingly similar facts, or his deeper view of what constitutes an invention. In Revolution, the patent addressed two problems presented by prior-art magnetic sunglasses that attached to the frame of a pair of glasses: a frame strength problem, which the inventor solved by placing the magnets on protrusions extending from the primary and auxiliary frames, and a stability problem, which the inventor solved by having the protrusions extending from the auxiliary frame rest on top of protrusions extending from the primary frame. The asserted claim covered only the former: placing the magnets on protrusions, and did not include any limitations directed to the stability problem.

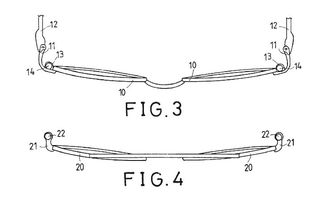

In rejecting the written description defense, the Revolution court pointed specifically to Figure 3 of the original patent, reproduced below:

This figure discloses only the combination embodiment: a primary frame with magnet-containing protrusions designed so that the auxiliary frame protrusions will rest on top (element 13/14 on the primary, 21/22 on the auxiliary). The court's opinion did not rely on any embodiments showing only magnet-containing projections without the stability component. Yet, under Judge Dyk's reasoning, such an embodiment could not provide the necessary written description support.

Moving into the abstract, Judge Dyk's view of the nature of an invention also seems problematic to me. Judge Dyk seems to be expressing the Louriean idea that "the invention" must be limited to the identical embodiments disclosed in the patent. Any alteration of those embodiments, such as combining one particular inventive idea disclosed in the patent with the prior art, renders the claim invalid. But this bright line rule ignores one of the underlying tensions in patent law, namely, that it is impossible to describe every single possible permutation of the invention. Patents don't need to specify, for example, that a particular device may be painted every color of the rainbow to provide written description support for a claim that contains no limitations as to color. Yet this seems to be the logical extension of the embodiment-only approach, and one that continues to be trouble me.

ping, actually these issues have been litigated and decided adversely to your position. You really need to read not only Muncie Gear, but Eagan v. Eaton (or vis-a-versa). The latter case had a spec. that simply described a machine. There was no effort to identify what was new about the machine. The Supremes held that this violated the WDR.

Ned-O gram,

Ya might have ta square this “That was fully descibed in the specification, but there was no hint that the anti-cavitation plate, or its features, was even new” induced idea that an applicant hasta scream out “THIS IS NEW HERE” with the fact that nothing old in the art need be presented again in an application. The basis in reading an application should be to assume everything is new unless explicitly and affirmatively stated otherwise by the applicant.

Max, Policy?

The public interest.

Regardless of what Muncie Gear actually held, it did find vice in changing the theory of invention after filing. Many have remarked, including the 2006(5?) FTC report, that changing the theory of invention is a real problem. The FTC advocated intervening rights while recognizing a “legitimate right” for applicants to claim what they actually disclosed.

The EPO has long recognized the problem by refusing any “reissues” that would broaden the claims. It further has limited the time for filing of divisionals for the same public policy reasons.

The public needs to read an application as a whole to determine what the applicant regards as his invention. The public needs to appreciate not only what the applicant is currently claiming to be his invention, but what he could claim. As in Muncie Gear, if there is no hint in the specification that a feature is even new, there is an essential failure of the written description requirement — and that is what the Supreme Court in Muncie Gear said was the problem with such a switch in theories. (I am talking here about the anti-cavitation plate as being the invention. That was fully descibed in the specification, but there was no hint that the anti-cavitation plate, or its features, was even new.)

Read the case and see if you agree.

link to supreme.justia.com

I couldn’t begin to answer that question accurately MM. I will note that my wild guess is 50%. I will also note that the percentage feels to me to be increasing, especially in cases where there could be some doubt as to where support would be coming from. I also encourage it as a best practice on the phone.

Max, you’ve identified one of the reasons that we need more than on search to do a good job in prosecution.

I agree we should pay for the additional searches. But I disagree with the whole concept that we should pay the full boat filing fee for the privilege and in addition be send to the back of the line.

Malcolm, if I have it right, your field is chem/bio. In physics and engineering things are different. As soon as I tell my PHOSITA my combination of technical features, it will tell me what performance I am going to get out of that combination. With hindsight knowledge of that combination, it is all “predictable”. But that does not prove that it was a combination of technical features that, just before the filing date, the state of the art rendered “obvious”.

That anyway is why I see it as dangerous nonsense in my field.

I know. But we have Supreme Court precedent, even precedent cited in Ariad, that holds exactly what I just said. Eaton v. Eagan, for example.

MD And by the way, “predictable” as a patentability criterion is dangerous hindsight nonsense.

Dangerous? Sounds scary.

Why, when determining patentability, is taking into account the predictability of (e.g.,) the functionality of a claimed combination “nonsense”? It seems like a very reasonable step in the determination of the obviousness of a claimed invention.

Agreed, but it’s a bit hard for them, isn’t it Ned? What I mean is, one can see the mischief when a tribunal in shrinks from revoking a claim that embraces something old or obvious or which is not enabled or not useful. But revoking something just because it is, say, not clear, strikes one as excessively harsh. Likwewise, striking down a claim, good in all other respects, just because it is directed to subject matter not “identified” in the app as filed, well, most will baulk at that, no?

What’s the compelling public policy reason to enforce the WDR in this way?

I’m not so sure you should sweep Lourie into this.

The Philips case was a lot more compelling that the baffle angles should have been included in the claim construction. They appeared to be an essential feature of the all disclosed inventions.

I have a question for 6 and any other Examiners who want to chime in.

What fraction (roughly) of amendments include statements from Applicants indicating specifically (by pointing to a line number, paragraph number, Table, or drawing) where support for the amendment may be found in the application as originally filed?

6 I’ll just go ahead and start rejecting another 25% of the amendments I get back based on this theory

First of all, I think it’s remarkable that 25% of amendments you see do not have verbatim written support in the specification. That just shows how many incompetent stooges there are drafting and prosecuting applications. I routinely amend claims to broaden them in one respect or another but I’ve got crystal clear disclosure for those embodiments 100% of the time, or close to it. Providing such support seems to be one of the most elementary aspects of the practice: start with the broadest characterization of what you’ve invented, and narrow it down.

I’m saying it is what goes on. And if I’m not going to ding everyone then I don’t ding anyone.

Yes, I understand that “what goes on” at the USPTO is typically very different from what goes on during litigation. To the extent you and your fellow examiners are consistent, at least, that minimizes some of the problems.

Tinla, we all know the answer. The applicant cannot change the spec without introducing a new matter problem.

I would say that the Board and the Feds ought to start enforcing the WDR. Part of that requirement is to identify the invention in the specification, not just describe how to make and use it.

6, I think that in view of Festo, that it would be disastrous if Examiners can force Applciants who specify the options in dependent claims to amend each of them to independent form on the basis that the independent claim is not patentable for lack of written decription or enablement. If a court invalidated the independent claim uner 112, then the applicant could still assert the dependent claims that do express the options under DOE. But if the Applicant is forced to amend to independent form, the claims become much narrower in scope than they were as dependent claims. And before you chime in that they should be filed as independent claims or separate applications, you have to know that is too cost prohibitive, and shouldn’t be required.

Thanks EG. If the inventive concept is “AB” then I would have an independent apparatus claim directed to “Means for A-ing and means for B-ing”, and an independent method claim directed to the process steps of “A-ing and B-ing”. Then I would have a string of dependent claims directed to optional features C,D,E,F and so on. In the spec, one would read how each one of CDEF delivers enhanced performance, stating explicitly what particular performance enhancement is delivered by each separate one of CDEF.

Whether AB is novel is relatively simple to decide. Whether AB is obvious will be decided in the EPO on the basis of what technical effects are announced in the app as filed, as being delivered by the feature combination “AB”.

Trouble starts when AB is notoriously old. For then you have a different invention for each of your dependent claims. And the EPO will search only one of them, per search fee paid by Applicant.

Even more trouble when Applicant tries to get to issue on the basis of a feature parachuted into the main claim, with no indication in the spec as filed that this feature delivers anything special.

Where international drafting is problematic is in the area of stating explicitly which performance enhancements flow from which features. Vital in Europe, deadly dangerous in the USA.

Do you know the sound-bite definition of new and potentially unobvious patentable matter, namely “A difference that makes a difference”. The EPO is practising exactly that criterion.

And by the way, “predictable” as a patentability criterion is dangerous hindsight nonsense.

Max,

I’ll take a stab at answering your question. What I would suggest doing is phrasing the “inventive concept” (as you call it) as more than one alternative embodiment. Usually, the “inventive concept” will have one or more core elements (e.g., A and B) to which you can add one or more secondary elements (e.g., C, D, etc.), phrased in the alternative. It’s very rare that I write an application that has only “embodiment” described in the summary section (for example, if there’s an article invention, there’s often a method/process invention go with it, or potentially multiple generic article embodiments that can’t be linked together easily or reasonably in one “inventive concept”). And to my knowledge, this doesn’t cause trouble elsewhere in the world, including Europe.

If you don’t have one or more common core elements in the “inventive concept,” that’s usually a signal to me that there’s more than one invention, each requiring its’ own application. For example, I know that provisionals written in the U.S. can have multiple inventions described (even unrelated ones); we refer to this as a “stack and roll” (i.e., because what are, in essence, multiple applications are “stacked” together to form a “roll”). These “stack and roll” provisionals are often divided out later into separate non-provisional applications (the multiple inventions would usually be divided out anyway due to restriction/election of invention requirements).

Does that answer your dilemma?

Wherever else I ask, nobody seems to have a useful answer.

Here, at least I get a laugh. Thanks for that, Cy.

What to do?

I suggest seeking advice on an Internet message board. I can’t think of a better way to ensure that I get nothing but thoughtful, measured, guidance.

EG, MM, can you help me with my drafting conundrum? For the USA, advantage accrues (as far as I can discern from cases like this), and risk is minimised, when one studiously avoids giving the reader of the specification any clue, what is the subject matter of the inventive concept, and what technical effects are delivered, by which technical features. For the rest of the world, though, following that course risks losing everything, and ending up with no protection at all. What to do?

“So what patent application drafting practice tip does this case teach us?”

Never use the phrase “characterized in that” anywhere in a patent application. Unfortunately, as I’ve noted above, no one in this case saw the real “written description” problem.

Illuminating. Thanks 6. I see your point. What else can a fair and reasonable Examiner sensibly do? It’s for the courts to set the standard, for the Office then to implement. Malcolm?

What the sam hill are you talking about? It appears that once again you are trying to say that I have said something that I have not.

strawman much?

Uh huh, sure MM.

In other news, I’ll just go ahead and start rejecting another 25% of the amendments I get back based on this theorylol and see myself with appeals stacked to the ceiling here soon.

Let’s be clear, I’m not saying it is the best thing to do. I’m saying it is what goes on. And if I’m not going to ding everyone then I don’t ding anyone.

On the contrary, ping. Many inventions are realisable as an apparatus and as a method. Talking about The States (as we were) I find that it always does take at least one divisional (and two sets of fees till the end of the patent term) simply to cover a single inventive concept ABC, as disclosed in the app.

At the EPO one would claim, as one “aspect” of the inventive concept, the method that comprises the steps of “A-ing, B-ing and C-ing” and, as another aspect of the single inventive concept, the apparatus that exhibits “Means for A-ing, means for B-ing and means for C-ing.” One patent, one set of fees, full coverage. That is quality.

“we aint gonna o it” aint “quality” by any measure.

Here in the States it dont take a divisional ta claim what ya already disclosed. TG

“Remember, we folks in the chem/bio arts have to play by the grown-up rules”

Lolz – same folks as shown by the Big D with one O the biggest error rates. Even bigger given that Sunshine be near perfect (least accordin to himself).

Malcolm, a confession and a tip.

First the confession. I had not intended in my hypo above to show in the app as filed a claim pprecisely to ABDE. It should have been ACDE (or anything else but ABDE).

The tip now. In the EPO they search first, examine later. They only search the invention that was “first mentioned” in the claims, and later they decline to examine any subject matter they have not already searched. Even if you can run an argument that the inserted ABDE claim does not add matter, you will (these days) run aground on the objection that it has not been searched so can’t be examined. Remedy: file a divisional.

The EPO set itself a target, some years ago, to “raise the bar”. On drafting standards displayed by patent attorneys, I discern that, on this measure of “quality”, it is having some success.

I found that little sequence most enlightening. Thanks both.

I’m not troubled by your misunderstanding of 112 1st.

I understand 112, 1st, 6. Remember, we folks in the chem/bio arts have to play by the grown-up rules. If you fail to disclose BCDE, then you are not in possession of BCDE.

I guess you could submit a declaration saying that one skilled in the art would have recognized at the time of filing that A is not essential. Of course, that leaves one wondering why you didn’t hire someone with some knowledge of the art to draft your patent specification.

Your general proposition may have legs for incredible obvious combinations of elements that wouldn’t be patentable anyway (such as your bicycle with the tard-shaped pedal) but for many inventions a disclosure as lame as the one you suggested will screw you, as well it should.

I think it would be unwise, to say the least, to rely on this case or any other written description case in which a claim was found valid to justify the short-cut taken in your hypothetical. That is why only m0r0ns will do so, and then they will come here and weep when their patents (or anybody else’s) go up in 112 1st flames in the district court or at the CAFC.

“”The invention is A+B+C+D+E””

I didn’t say “the invention is” I disclosed a bicycle, in standard “in an embodiment” bs format in the spec, and the standard claim exactly what you disclosed format in the original.

Maybe I should be more clear then since it isn’t apparent that I’m following standard format.

Spec:

Background: BS about irrelevant related art.

Figure Summary: Fig. 1, is of my coc k which is related art according to me. (feel free to object lulz)

Fig. 2 is of Mila Kunis in a compromising position. Again, feel free to object.

Summary of the invention:

In an embodiment the invention includes a bicycle including a star-shaped pedal, a gear, a front wheel, a back wheel and a frame. Another embodiment includes blah blah blah.

Detailed description:

An embodiment of the invention includes a bicycle comprising: a star-shaped pedal, a gear, a front wheel, a back wheel and a frame. In another embodiment blah blah blah blah.

Claims:

Claim 1. A bicycle comprising:

a star-shaped pedal, a gear, a front wheel, a back wheel and a frame.

After a non-final rejection where the examiner failed to make out a prima facie caselol I add claim 2.

Claim 2. A bicycle comprising:

a gear, a front wheel, a back wheel and a frame.

I also add claim 3.

Claim 3. Isolated Mila Kunis in a compromising position.

Composition of matter btches.

“Not sure why this any of this is so troubling to you (or why it would concern any competent patent drafter).”

So troubling to me? I’m not troubled by your misunderstanding of 112 1st. Apparently hanging out with all those composition of matter claims has left you forgetting how things are routinely claimed and routinely properly amended in the mech arts. You most certainly do not need a statement stating that A is non-essential or a working example without A in it.

Note that exactly what the majority held here is exactly what I’m doing. And, btw, that’s what the lawl is and has been at least since I started here.

You have explicit support for abcde and go to claim bcde later

Right. And there’s nothing else in the specification as filed except “The invention is A+B+C+D+E” and a claim reciting same? And now you want to claim “BCDE”?

No possession, my friend. No can do. At least not legally.

Now, if you’ve got more in your spec (say a description of several working examples without element A) then you’ve got a chance. Likewise, if you have a statement that “None of the elements A, B, C, D, or E is strictly essential and any one of the elements may be omitted without affecting the utility of the invention” or something of that sort you are in far better shape.

On the other hand, an additional teaching that “The prior art does not teach A in combination with B, which is an essential feature of the present invention” then you might be be screwed even if you do have literal support for a composition comprising only BCDE.

Not sure why this any of this is so troubling to you (or why it would concern any competent patent drafter).

You keep mouthing off about how my example is not as clear as I could have made it but you apparently don’t want to say why. It appears quite clear enough to me. You have explicit support for abcde and go to claim bcde later. That is just fine. Routine even.

6 But here in the USoA the likelyhood of getting a Fed. Circ. panel to sign off on that as a legit WD rejection is slim to the more probable 0.

Not in the situation you described in your “clear” hypothetical. It’s nearly 100%.

So what patent application drafting practice tip does this case teach us?

ping, ok, obligue angles. See, Philips.

How many examiner hours would it take to get to the bottom of 1 Meeellion pages of consideration?

(pinkie in corner of mouth)

lolz Ned-o.

As I done asked before – 90 and zero degrees are still angles, amirite?

Okay MM, whatev you say. I agree about the EPO but they do things super strict. But here in the USoA the likelyhood of getting a Fed. Circ. panel to sign off on that as a legit WD rejection is slim to the more probable 0.

I should also note that I often get specs where the only relevant words are 17 words and a claim that recites the exact same thing.

Recall, that this very same issue occurred in the Philips case. The specification disclosed “baffles” for two purposes: structural support and bullet deflection. An angled baffle was critical for bullet deflection, but was not critical for structural support. (I have not read the specification so I say this only from the Federal Circuit’s opinions themselves.)

We know the result in Philips. The majority held that if a baffle had more than one purpose, the details of the specification unnecessary for that purpose need not be included in the claim construction.

In that case, Lourie unsuccessfully argued in dissent that the angles of the baffles had the be included because there were no other embodiments disclosed.

I think Phillips was a close case. It is not clear (from the opinions) that a baffle that was not angled could provide the necessary structural support. Were the angles critical for that purpose as well? That was a question that was never addressed and never really answered by the majority.

In contrast in this case, the majority did address the issue of whether the narrow beads were critical. They were not for the metal saving invention by flattening the can flanges.

Well, 6, I’m currently on the planet where I my specification contains more than 17 words and a claim that is identical to the specification. According to your “clear” hypothetical, it would be perfectly reasonable for the PTO or a court to find that the removal of any of the elements constitutes new matter. For what it’s worth, that is almost surely what would happen to you in the EPO.

But maybe you weren’t as “clear” as you intended to be when you stated your hypothetical.

“Is the combination ABDE still patentable for WD purposes? Enablement?

Same facts, but remove the statement in the spec that C is necessary. What then?”

My same answer as above.

In other words:

1. yes.

2. probably, though not definitely, no.

3. Yes

4. probably, though not definitely, no. And since they didn’t mention it in the spec then you’re going to have to go find other evidence of it being essential and the lack of it being there rendering the abde not enabled. Or evidence that just plain ol’ abde is not enabled.

MD, my understanding of EPO practice is that the amendment would likely be accepted in that situation. Of course, if there is any interest in the patent, then there will likely be a new matter issue raised in opposition regardless.

Btw, i4i oral argument is Monday I do believe.

And why do you say that MM? Let me be clear. I disclose

a bicycle comprising: a star-shaped pedal, a gear, a front wheel, a back wheel and a frame.

I initially claim exactly that.

I’m not allowed, by the WD req, to claim:

a bicycle comprising a gear, a front wheel, a back wheel and a frame. (note no pedal recited)

in my amendment? If yes, I’m not allowed, which patent prosecution planet did you fall off of?

O it be better than that crelboyne,

Just wait until the i4i decision and the IDS trucks be pullin in with 1,000’s of them there 1,000-page specifications.

Wont that be a hoot!

You seem to be making this way too complicated. Also, I doubt very seriously that the courts making the call one way or the other on those very complicated hair splits can be termed a “disaster” as opposed to simply how the ball bounces when you choose, of your own free will, to try to use bs words instead of structure or steps. Remember, you’re the one doing the initial disclosing, nip the problem in the bud during drafting if you’re so in possession of whatever it is you’re wanting to claim later.

So Judges Dyk and Lourie want 1,000-page patent specifications? Having to list (let alone read through) every possible range or number permutation is mind-numbing.

“So, 6, TIN, do you think the 25 year old EPO 3-step test has anything to commend it? It goes like this:”

No because we’re not talking about the EPO test.

“What if the specification contains a statement that C is necessary, and the reason that the applicant realized that C was not necessary is because a competitor found another element, F, that is not structurally or functionally equivalent to C, and that when added to the combination renders C optional.”

Then a 112 2nd or 112 1st enablement req will probably stop the original application from claiming ABDE. Remember, enablement is judged at the time of filing (so far as I’m aware) not at the subsequent time of someone else inventing F that makes C optional.

MM I had in mind the (for me) typical situation of an app, incoming from the USA (or Japan) with a plurality of different “aspects” of “the disclosure”, all reciting different feature combinations, like: claim 1 has ABCDE 12 has ABCF, 22 has ABDE, and 32 has ABEF. I argue: C is not presented consistently as essential. Ergo: C is not essential.

So, 6, TIN, do you think the 25 year old EPO 3-step test has anything to commend it? It goes like this:

1. Does the app consistently teach that C is essential? If Y you can’t remove it. If N:

2. Is C in fact essential for delivering what the app promises? If Y, you can’t remove it. If N:

3. Would removing it force substantial re-design? If Y, you can’t remove it. If Y, you can.

TIN, it bothers me that in your hypo you have to explore the motives of the Applicant. Is that efficient or fair to third parties?

Both: all this in the EPO under the rubric of whether prosecution amendments “add subject matter”. But nothing at all to do with adding subject matter at the USPTO, right?

Cy,

Since when did that ever stop 6 befores?

OK. Suppose the originally filed disclosure and claims is of a machine with structural features A through E. During prosecution, the inventor and attorney realise that feature C is not essential, and file an amended claim directed to ABDE, with an argument that the feature arrangement ABDE is present, arranged exactly the same way, in the app as filed. Allowable?

It shouldn’t be. I mean, what is the “argument” you refer to? That something is disclosed in the specification even though it isn’t?

If you have no support for the amended combination, you are out of luck. Again, if you’ve been prosecuting applications in the EPO for any period of time, you’ve already adjusted your specifications to avoid this problem.

“Sure under WD req.”

What if the specification contains a statement that C is necessary, and the reason that the applicant realized that C was not necessary is because a competitor found another element, F, that is not structurally or functionally equivalent to C, and that when added to the combination renders C optional.

Is the combination ABDE still patentable for WD purposes? Enablement?

Same facts, but remove the statement in the spec that C is necessary. What then?

Indeed, there are substantial indications that one could mount an enablement attack on these claims. You would probably need an expert witness and also you might need to make some wands findings unless the expert witness could tell you something that would indicate that some embodiments within the claim are plainly not enabled. Big whoop. It isn’t that hard to do.

Big whoop, says the guy with exactly zero litigation experience.

Understood.

The main concern, from my view, is that Judges and others could misapprehend the context, especially that the claims in Lizardtech and Liebel-Flarsheim essentially claimed a result or capability, without an accompanying limitation regarding how that result is achieved or capability provided. Or if they do understand that context, they may still attempt to extend the broad ruling to invalidate claims of scope capable of reading on devices having features not recited in the claims, as opposed to having a feature exhibiting the recited result or capablity, but achieving that result or capability in a substanitally different way than that disclosed in the specification.

Hairs still need to be split over whether a prima facie case can be established by an Examiner alleging that a claim element lacks written description because it recites a result or capability, without specifying any way of achieving that result or capability, even though the disclosure setails one or more options. In Lizardtech and Liebel-Flarsheim, for example, the alleged infringing device established that an undisclosed solution existed. But in prosecution, it seems reasonable that the Examiner should have to present prior art, or an affidavit, to establish that another solution exists. Additionally, that undisclosed solution should have to be a non-equivalent of any of the disclosed solutions.

I don’t know about you, but I have some skepticism that the Courts will be able to split these hairs with the precision necessary to avoid disaster.

“OK. Suppose the originally filed disclosure and claims is of a machine with structural features A through E. During prosecution, the inventor and attorney realise that feature C is not essential, and file an amended claim directed to ABDE, with an argument that the feature arrangement ABDE is present, arranged exactly the same way, in the app as filed. Allowable?”

Sure under WD req.

To be clear, if they specifically state (in the spec or, g od forbid, in the claims themselves) that the feature C is ESSENTIAL then, on your facts you have a potential problem under 112 1st para enablement req or 112 2nd. And if they don’t say jack in the spec about it being essential then you don’t have an issue with essential subject matter at all. This is the way the lawl has been decided for quite some time now. For good or ill.

If they do talk about essential subject matter then you might need to see my good friend 112 2nd about a rejection. There is also a FP for a rejection under the enablement req. regarding subject matter indicated as being essential to the practice of the invention but I always presumed that this was simply a variant of a normal enablement req rejection that happened to deal with subject matter which was not claimed, but was indicated in the spec as being reqed to practice the claimed invention (i.e. it is essential). In other words, may as well just state it in traditional enablement rejection terms.

I personally never run into this “essential subject matter” stuff myself because even as bad as the drafters writing the horse sh it I have to look over are, they’re still not bad enough to put in the spec that something is essential or “required”. Occasionally I catch someone trying to claim something that would have to use a non-enabled method to make a claimed product or a non-enabled sub-method to perform a claimed method and I use that enablement rejection I mentioned above. But basically it is just another enablement rejection because in the end you just can’t perform the method or make the product (usually) because it is impossible. And this usually happens due to drafting/wording errors, not because my applicants are retar ded enough to submit apps for subject matter that plain doesn’t work. They just have a hard time putting it down on paper properly.

One time my boss wanted me to reject a claim for not reciting “essential subject matter” found in a parent claim because it would amount to a gap between the steps if it were not recited in the dep as well. And to be truthful the dep was kind of weird without having that step put in but I was skeptical but the rejction in there to appease him, the applicant amended (probably to appease us) slightly and I just glossed over it in the next action, considering it to be fixed, if there ever was a problem in the first place.

While the flattening was independent of narrowing the bead for metal savings, the converse was not true. Narrowing the bead would make the apparatus non functional due to scuffing an breakage. It required a flat flange against which the chuch could press.

The actual result here and the analysis seems correct, but I can also see Dyk’s point.

There is no “esssential features” or “essential elements” or “Omitted elements” test – it’s all written description. If you are speaking about an invention that will not work as claimed, that is an enablment issue.

“In so stating, we did not announce a new “essential element” test mandating an inquiry into what an inventor considers to be essential to his invention and requiring that the claims incorporate those elements. Use of particular language explaining a decision does not necessarily create a new legal test. Rather, in Gentry, we applied and merely expounded upon the unremarkable proposition that a broad claim is invalid when the entirety of the specification clearly indicates that the invention is of a much narrower scope. (“[C]laims may be no broader than the supporting disclosure.”) (Cooper Cameron v. Kvaerner 291 F.3d 1317 (Fed. Cir. 2001), quoting Gentry Gallery, Inc. v. Berkline Corp., 134 F.3d 1473, 45 USPQ2d 1498 (Fed.Cir.1998))

OK. Suppose the originally filed disclosure and claims is of a machine with structural features A through E. During prosecution, the inventor and attorney realise that feature C is not essential, and file an amended claim directed to ABDE, with an argument that the feature arrangement ABDE is present, arranged exactly the same way, in the app as filed. Allowable?

Je sus sorry that should be:

For a claim that is practically all structurally defined: look to the originally filed spec/claims (aka the application), see if all structural features recited in the instant claim are recited in the ORIGINALLY FILED SPEC/CLAIMS as arranged in the INSTANT CLAIM.

I keep posting before I proofread.

Well thanks for that 6, but I’m still struggling. You wrote:

“see if all structural features recited in the instant claim are recited in the specification as arranged in the spec.”

but did you perhaps intend “….as arranged in the claim” (because that, for me, would make more sense).

“For a claim that is practically all structurally defined: look to the originally filed spec/claims, see if all structural features recited in the instant claim are recited in the specification as arranged in the spec.”

Sorry should be:

For a claim that is practically all structurally defined: look to the originally filed spec/claims, see if all structural features recited in the instant claim are recited in the specification as arranged in the CLAIM.

That excerpt does not alarm me at all. Matter of fact, I think I even went over that case myself and understood why enablement was an issue. Even if I didn’t, a finding of non-enablement is hardly cause for me to be concerned. It happens, and again, enablement might very well be an issue in the instant case, but nobody argued it. Indeed, there are substantial indications that one could mount an enablement attack on these claims. You would probably need an expert witness and also you might need to make some wands findings unless the expert witness could tell you something that would indicate that some embodiments within the claim are plainly not enabled. Big whoop. It isn’t that hard to do.

On the other hand, at this point it looks to me that everything in the instant case is perfectly enabled.

Although of course validity based upon any of the above findings, if they were made, is a question for a court to resolve and I have no opinion on.

the only thing I llike about this comment is the stylings of the commentors name.

Flattery.

“Can you tell me, short and snappy, what actually is the correct legal logic for the majority decision. I can’t make it out from what you have already written.”

For a claim that is practically all structurally defined: look to the originally filed spec/claims, see if all structural features recited in the instant claim are recited in the specification as arranged in the spec.

The disclosure can be implicit or explicit. State yes or no to whether the structure as claimed is found in the originally filed application.

End of analysis.

And, to be clear, even though Newman and the author waxed poetic about the functional/intended use (is saving metal a function or an intended use aka a “result”? lulz, your call) nonsense they probably did the correct analysis behind the scenes. They just went too far and worded it bizarrely because they had to deal with the nonsense badly worded in the cited caselaw, which, if you go look, actually dealt with functional terms. The instant claims have jack to do with the functionality.

So maybe now you see, having been presented with the views of the District Court and at least one CAFC Judge, why there has been so much concern over the way more than a few people want to apply 112 WDR, especially after Lizardtech.

There is a line of similar cases on 112 enablement, and if you want more cause for alarm, I suggest you check out Bernard Chow’s Stanford Law Review article. Here is a telling excerpt:

“In Liebel-Flarsheim, the invention was a front-loading fluid injector system with a replaceable syringe capable of withstanding high pressure for delivering a contrast agent to a patient. The specification only described an injector with a pressure jacket but the asserted claims did not mention the pressure jacket. As a result, the Court construed the claims to include an injector with or without a pressure jacket. However, the breadth of the claim led to a lack of enablement finding.”

Imagine if Judge Dyk’s view had prevailed; would the USPTO be rejecting every claim going forward that has the word “comprising” in it?

I for one, am breathing a sigh of relief that at least this prong of 112 has been settled satisfactorily, at least for now.

6, you write: the CAFC managed to stumble blindly into the right result

Can you tell me, short and snappy, what actually is the correct legal logic for the majority decision. I can’t make it out from what you have already written.

You see it like I do Max. That “characterizing” language is really dangerous, and definitely not recommended on this side of the pond either.

Note also this statement from the majority opinion:

“Nowhere does the specifica-tion teach that metal savings can only be achieved by increasing the chuck wall angle along with narrowing the reinforcing bead.”

Well, that statement isn’t true either if you accept the “characterizing” language in these patents at face value. Obviously, the District Court judge (Whyte) who wrote this opinion isn’t familiar with what EPO-style “characterizing” language means, although I would expect Judge Newman who joined the majority opinion to be familiar with such language.

I would have agreed with the majority opinion if this “characterizing” language wasn’t in the patents and the angle-bead features had been phrased in the alternative. But what blows my mind is that no one, be it the majority opinion, the dissenting opinion, or even the parties addresses what the impact of this “characterizing” language.

6 writes: The only question is whether or not some embodiments covered by the claims would not have been enabled.

which has the merit of being short and snappy. Not sure he’s right though. More comments please.

“Crown’s asserted claims are not broad genus claims or

function claims simply describing the desired result of

saving metal.”

W t f? The claims can certainly be characterized in terms of the genus species relationship, just as any claim can. In this case, it is the genus of the specific can top that includes every can lid with the specified features. That is fine to call that a genus and the individual embodiments within that the species within the genus.

“Therefore, the critical question is whether

the specification, including the original claim language,

demonstrates that the applicants had possession of an

embodiment that improved metal usage by increasing the

slope of the chuck wall without also limiting the width of

the reinforcing bead”

LOL WUT? Why in the sam heck would you bring functions or functional language into play? Why care about “improved metal usage”? It isn’t recited in the claim, the claim is fairly characterized by all structural limitations with a few “adapted to’s” in areas that are not at issue here.

”

Crown relies on our decision in Revolution Eyewear

for the proposition that “[i]nventors can frame their

claims to address one problem or several, and the written

description requirement will be satisfied as to each claim

as long as the description conveys that the inventor was

in possession of the invention recited in the claim.” 563

F.3d at 1367. In this case, Crown contends that the

specification teaches two separate solutions for improving

metal usage: increasing the slope of the chuck wall of the can end and limiting the width of the reinforcing bead.

According to Crown, nothing in the specification requires

employment of both methods in all instances. Where one

does not elect to limit the width of the reinforcing bead,

Crown contends that driving can occur either inside or

outside of the reinforcing bead. ”

There’s the problem, some counsel got the court all confused by making that weird arse argument.

Note to the CAFC, decide cases on the merits not on whatever bogus caselawl cites the attorneys feed you.

“Revolution Eyewear by

arguing that the specification here mandates that the

prior art problems (metal usage and risk of damage with

a narrower reinforcing bead) must always be solved

together. ”

So tell us about enablement tard.

In the end, at least we can look on the bright side, the CAFC managed to stumble blindly into the right result and note what the proper basis for an invalidity attack would have been.

And finally, I recommend that no prosecutor worth his salt toss his hat into the ring based on these premises of function in a WD dispute about a claim that doesn’t even have functional limitations at issue. You will receive an even swifter smack down by someone who knows what the f is going on.

P.S. I’m disappointed in Dyk’s performance in this case. Embarrassed for him even. Maybe he was just having a bad day.

“Ball argued that these claims lacked written description support because they covered embodiments both in which the chuck was driven inside the reinforcing channel as well as embodiments in which the chuck was driven outside the bead despite only describing embodiments showing the latter in the specification. The district court agreed with Bell, granting summary judgment of invalidity.”

Lol wut? No special doctrine is needed to resolve that issue. The DC made a mistake. Pure and simple.

“Relying on Revolution Eyeware, Inc. v. Aspex Eyewear, Inc., 563 F.3d 1358 (Fed. Cir. 2009), the court agreed with Crown that “[i]nventors can frame their claims to address one problem or several, and the written description requirement will be satisfied as to each claim as long as the description conveys that the inventor was in possession of the invention recited in the claim.” Slip Op. at 13, quoting Revolution Eyewear at 1367. Here, there were two separate, clearly described solutions to the problem of improving metal useage: modifying the slope of the wall or limiting the width of the reinforcing bead. ”

Completely irrelevant. The applicant’s decision to omit some features in a claim does not in any way affect the WD for the features that are left in the claim.

“And the majority distinguished the issue of enablement from that of written description, concluding that Ball’s argument relating to whether one of ordinary skill in the art could not seam a can with an increased sloped chuck wall without also avoiding contact with the reinforcing bead presented an issue of enablement, not written description. ”

That is true, but there is no issue here. If the angled can claim was enabled then it is enabled, regardless of whether or not they recited the extra features of the chuck, chuck action or whatever. You don’t have to recite something like “enabling portions” of an embodiment in your claim for it to maybe be enabled. The only question is whether or not some embodiments covered by the claims would not have been enabled. That could very well be a problem in this case but I see no wands factors or whatever.

“One possible limitation on the majority’s holding, however, is where the specification mandates that the prior art problems must always be solved together. ”

Retar ded. None of this has to do with any problems or solutions. If you want to make an “essential features” 112 2nd argument then fine, but that has ja ck to do with WD.

I don’t even see how it is possible for people to be so confused on the subject of 112.

“There is no question that the specification does not teach combining the sloped can end wall together with the wider, prior art bead and driving the chuck into the bead instead of the sloped can end wall. ”

Um, irrelevant.

“That combination is a new and distinct invention, and our written description jurisprudence requires that it be described in the specification. ”

Again, irrelevant.

Lordy lordy.

Claim 13 at least appears to be describing an embodiment like Fig. 5. W T F would make someone think differently?

All that said, the majority bonked this decision just as badly as the dissent.

Well EG, I for one am surprised by the c-i-t language used here. As far as I know, out on the British islands, claim drafting in the EPO-favoured “two part form” is generally seen as beyond the pale, risky, and disadvantageous to the Applicant.

I sense an international tendency, within the community of those who adjudicate patents, to force a “raising of the bar” in the standards they impose on those who draft patent applications. “Be careful what you ask for” and “Don’t ask, don’t get” might be their warning, these days.

“According to Crown, nothing in the specification requires employment of both methods in all instances. Where one does not elect to limit the width of the reinforcing bead, Crown contends that driving can occur either inside or outside of the reinforcing bead.”

Scratch my statement about the “narrow concave bead” feature not being illustrated as I now understand what this feature is. But the above statement by Crown from the case is simply not true. The “characterizing” language used in each of the patents clearly implies that both the angle and the narrower bead width are required for this invention. In other words, whether the driving inside or outside or outside the bead isn’t the issue. Instead, each of these patents, by the “characterizing” language used, requires both the angle and the narrower bead width, as is recited in Claim 5 of the ‘826 patent.

“Moving into the abstract, Judge Dyk’s view of the nature of an invention also seems problematic to me. Judge Dyk seems to be expressing the Louriean idea that “the invention” must be limited to the identical embodiments disclosed in the patent.”

Jason,

Dyk’s dissent may not be off target on the WD issue, but for a different reason. In typical European style, the invention is referred to in each patent as being “characterised in that, the chuck wall is inclined” at a 30-60 degree angle “and the concave bead [is] narrower than 1.5 mm.” (That’s not surprising given that the two patents in this suit claim priority to a British application.

) In other words, the “characterizing” language of these patents implies that both the chuck wall having 30-60 degree angle and the narrower concave bead are required for this invention.

These patents might have avoided this potential WD issue entirely by phrasing the “chuck wall of 30-60 degree angle” and “narrower concave bead” features in the alternative (“or”). But I’m still stumped as to why the “narrower bead feature” is even mentioned in the “characterizing” language. After reviewing each of these patents, it is unclear to me where this “narrow concave bead” feature is illustrated in either of these patents. Nor does the majority opinion address where this “narrow concave bead” feature is illustrated in either of these patents. If this “narrow concave bead” is nowhere illustrated in these patents, then why is it there?

I believe the important distinction to draw from the written description requirement is that support can be found for an invention that was not recognized by the applicant when filed but is readily aparrent to a person of ordinary skill in the art. I believe Judge Dyk’s ruling confuses these two situations. Judge Dyk appears to be saying that were an applicant not to recognize the invention when the application is filed then he is not in posession of it. However, I think the law is otherwise.

Excellent comment from Anon. Many of the tenets of patent law are universal, but go under different names in the US Statute and the EPC. The “in possession” notion fits well with Article 123(2) of the EPC, prohibiting prosecution amendments that “add subject matter” to the original filing. Then there is the caution from the EPO Boards of Appeal, to distinguish carefully between the “information content” of a claim and the “scope” which it defines. Not the same thing at all.

Perhaps a better way to think about how Lourie and Dyk are treating embodiments in the specification is from the “possession of the invention” aspect of section 112. This approach seeks to prevent patentees from claiming what they didn’t invent.

There’s no question that in Revolution Eyewear, the inventor was fairly in possession of the “magnets only” embodiment you described in your comment:

“The “decreased strength” problem originated from the design of the prior art frames, in which the magnetic materials were embedded in the frames, thus requiring the excavation of four or more cavities in a frame. Id. col.1 ll.33-37. In Chao’s invention, the magnetic members are supported by projections located at the rear/side portions of both the primary frame and the auxiliary frame. Id. col.2 ll.36-38, ll.43-44. Because the magnetic members are not embedded in the frames, the strength of the frames is not decreased. Id. col.3 ll.24-26.” 563 F.3d at 1363 (last sentence is particularly on point; sorry can’t figure out HTML tags to emphasize).

So, there was written support for the claim, even if the claim was directed to only one of the two stated problems of the prior art. The problem with Crown Packaging’s patent appears to be that it claims something that was not invented, i.e., it was not fairly disclosed by the specification. The written description did not evidence that the inventor was fairly in possession of the invention, unlike Revolution Eyewear.

I’d also submit that this is a problem that goes deep enough that it can’t be cured by including the subject matter in the original claims. If the claims are the only place where this subject matter appears, there’s a *serious* enablement problem. Which was recognized by the Crown Packaging court, at least.

The highly fact-specific nature of each patent’s specification and claims makes a universal rule difficult to formulate and apply across different technologies. But Dyk and Lourie seem to be expressing a deep discomfort with allowing patentees to claim unsupported subject matter, perhaps because it appears these patentees are claiming things they did not invent, or have only a thimbleful of support in the specification, at best. I think of this not as an embodiment-only approach, but rather use of embodiments to illustrate the limits of what the patentee has invented, as a point of reference to what the patentee tries to claim.

Many thanks Jason and Dennis. I had been hoping for a discussion of this case. What a nice opening of the discussion. Now we just need a thoughtful thread. Meanwhile, I must put on my specs and re-read that Eyewear case.

If anything, this case is closer to satisfying the written description test than Revolution Eyewear. Here, the disputed language was part of the original claims, whereas in Revolution Eyewear the language was newly added in a reissue. Granted, this means less with functional claims to a genus, but Dyk’s attempts to push this wholly to the other side of Revolution Eyewear don’t do much more me.

Comments are closed.