Guest Post by Prof. Jorge Contreras of the University of Utah S.J. Quinney School of Law. Disclosure statement: in 2019, the author served as an expert for HTC in an unrelated, non-U.S. case.

In August 31, 2021, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled in HTC Corp. v. Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson, 2021 U.S. App. LEXIS 26250, __ F.4th __ (Fed. Cir. 2021), affirming the judgment of the District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 170087 (E.D. Tex. 2019). The decision is significant as it is the first by the Fifth Circuit to address the licensing of standards-essential patents and the meaning of “fair, reasonable and nondiscriminatory” (FRAND) licensing terms, adding to the growing body of jurisprudence already issued by the Third, Ninth and Federal Circuits in this area. It is also significant because the court addresses several issues that have become increasingly important in standards-related litigation including (1) the apportionment of value among components of a multi-component product, (2) the proper choice of law for FRAND disputes, and (3) the interpretation of the “nondiscrimination” prong of the FRAND commitment. These issues all arose in connection with HTC’s challenge to District Judge Rodney Gilstrap’s jury instructions regarding FRAND. His vague charge appears to reflect the general uncertainty in this area, not only of the Texas district court, but of the entire judicial system. One can almost hear the weariness permeating the final sentence of Judge Gilstrap’s charge to an admittedly perplexed jury: “Ladies and gentlemen, there is no fixed or required methodology for setting or calculating the terms of a FRAND license rate.”

Background

Though it was never a household name in the U.S., HTC — founded in Taiwan in 1997 — was an early smartphone pioneer. In 2005 HTC released the world’s first Windows 3G smartphone (the clamshell HTC Universal) and followed in 2008 with the first smartphone running Google’s Android operating system (branded as the T-Mobile G1). Most significantly, HTC was the developer and manufacturer of Google’s Nexus One Android phone, which was released in 2010.

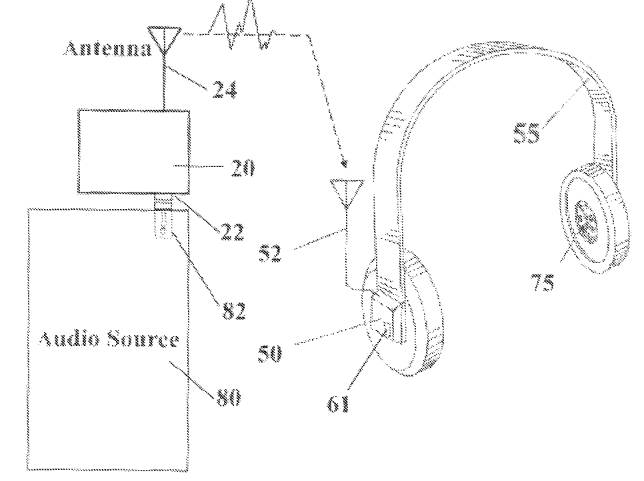

The 2/3/4/5G wireless communication standards published by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) are incorporated into almost all smartphones (and many other devices) that have been sold over the past two decades. These standards are covered by tens of thousands of patents around the world (standards-essential patents or SEPs), a respectable number of which are held by Swedish equipment manufacturer Ericsson. Most standards-development organizations (SDOs) today recognize the potential leverage that the holders of SEPs may hold over manufacturers of standardized products. FRAND licensing commitments are designed to alleviate the risk that SEP holders will prevent broad adoption of a standard by asserting their patents against manufacturers of standardized products. As explained by the Fifth Circuit, “To combat the potential for anticompetitive behavior, standard setting organizations require standard-essential patent holders to commit to licensing their patents on … FRAND terms” (slip op. p. 4). Thus, under ETSI’s intellectual property policy, which dates back to 1993, Ericsson and other holders of patents that cover ETSI’s standards agree to grant manufacturers licenses on FRAND terms.

Ericsson and HTC entered into three such licensing agreements in 2003, 2008 and 2014. Under the 2014 agreement, HTC paid Ericsson a lump sum of $75 million for a 2-year license to use Ericsson’s 2/3/4G SEPs. In 2016, HTC and Ericsson began negotiations to renew the license. Ericsson proposed a rate of $2.50 per 4G device, which was based on the lump sum paid by HTC in 2014 divided by the number of phones sold by HTC over the license period. HTC did not accept this offer and instead conducted an assessment of the value of Ericsson’s SEPs. It made a counteroffer of $0.10 per device in March 2017. Negotiations stalled, and in April, HTC brought an action in the Eastern District of Texas seeking a declaration that Ericsson had breached its obligation to offer HTC a license on FRAND terms.

The trial focused largely on the proper method for determining a FRAND royalty for Ericsson’s SEPs. Because the actual FRAND royalty or royalty range in a given case is generally viewed as a question of fact, the case was tried a jury, and each party submitted a set of draft jury instructions to the court. As summarized by the Fifth Circuit, “HTC proposed highly detailed instructions to help the jury interpret FRAND, but Ericsson objected to most of these instructions and proposed a more general FRAND instruction. The district court considered the two proposals, but ultimately gave the following instruction to the jury: ‘Whether or not a license is FRAND will depend upon the totality of the particular facts and circumstances existing during the negotiations and leading up to the license. Ladies and gentlemen, there is no fixed or required methodology for setting or calculating the terms of a FRAND license rate.’ (slip op. at 6). The jury returned a verdict “finding that HTC had not proven that Ericsson had breached its FRAND duties and that both parties had breached their obligations to negotiate in good faith.” (slip op. at 9]. On the basis of the jury verdict, Ericsson moved for declaratory judgment that, in its dealings with HTC, it complied with its FRAND obligations. The court granted Ericsson’s motion.

HTC appealed the district court’s ruling on three grounds: it failed to adopt three of HTC’s proposed jury instructions, it incorrectly concluded that Ericsson’s licensing offer complied with its FRAND commitment, and it improperly excluded expert testimony as hearsay. The Fifth Circuit, in an opinion authored by Judge Jennifer Walker Elrod, affirmed the lower court’s ruling on all three grounds. Judge Stephen A. Higginson entered a separate concurring opinion, arguing that the district court erred by omitting HTC’s apportionment jury instruction, but this omission did not rise to the level of reversible error.

Apportionment

In patent infringement cases, it is well-established that a patentee’s damages should reflect only the value of the patented features of an infringing product. Thus, in assessing damages, courts routinely “apportion” the infringer’s profits between the infringing and noninfringing features of its product. See Garretson v. Clark, 111 U.S. 120, 121 (1884). Accordingly, HTC argued that the district court erred by failing to give the jury specific instructions on apportionment.

However, this case did not sound in patent infringement, but in breach of contract. As my co-authors and I have previously observed (see p. 162), it is a peculiar coincidence of U.S. law that both the statutory measure for patent damages under 35 USC § 284 and the FRAND commitment call for the imposition of a “reasonable” royalty. For this reason, several U.S. courts that have calculated FRAND royalty rates (see, e.g., Ericsson v. D-Link (Fed. Cir. 2014), Microsoft v. Motorola (9th Cir. 2015); and Commonwealth Sci. & Indus. Research Org. (CSIRO) v. Cisco (Fed. Cir. 2015)) have looked to traditional methodologies for determining reasonable royalty patent damages, including the 15-factor Georgia-Pacific framework. But while this methodology may be useful by analogy, it is not strictly required, as the damages flowing from a breach of the contractual FRAND commitment must, by their nature, be determined under applicable principles of contract law. As the Fifth Circuit explains, “while the Federal Circuit’s patent law methodology can serve as guidance in contract cases on questions of patent valuation … it does not explicitly govern the interpretation of contractual terms, even terms that are intertwined with patent law” (slip op. at *15). As such, the Fifth Circuit in this case held that the district court’s omission of a specific jury instruction on apportionment – a patent law doctrine – was not error.

Judge Higginson disagreed. Citing D-Link and CSIRO, he observed the Federal Circuit’s “unmistakable command that a jury assessing patent value must be instructed on apportionment” and that “the failure to instruct a jury on proper apportionment is error when the jury is asked to assess patent value” (slip op. at *29-30, Higginson, J., concurring). And while he acknowledges that the instant case concerns breach of contract rather than patent infringement, he argues that the Federal Circuit’s precedent regarding apportionment is instructive “because a jury assessing patent infringement damages undertakes the same task of assessing whether an offered rate is FRAND” (citing Realtek Semiconductor, Corp. v. LSI Corp. (N.D. Cal., 2014) (slip op. at *30). Moreover, Judge Higginson points out that both HTC and Ericsson, as well as the United States as amicus curiae, requested jury instructions on apportionment. For all of these reasons, he concludes that the district court erred by omitting an instruction on apportionment.

Whether or not the district court erred, none of the Fifth Circuit judges felt that the omission of a specific apportionment instruction constituted reversible error because HTC had the opportunity to, and did, discuss apportionment during its closing argument before the jury. This observation raises interesting questions regarding the basis on which juries are expected to make decisions in complex cases. During trials that often last for weeks, the members of the jury hear hours upon hours of conflicting expert testimony and argumentation. Under Rule 51 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, a trial judge must instruct the jury regarding the substantive law governing the verdict. Its instructions are intended to distill the legal standards that the jury must apply during its deliberations. Given that members of the jury are not permitted to take notes or make recordings during trial, they must rely heavily on these court-sanctioned instructions. And contrary to the Fifth Circuit’s holding, it does seem problematic for a court to omit instructions that are germane to the jury’s deliberations concerning an area of law as complex as FRAND royalty determinations. In such cases, irrespective of what courts and commentators believe the law to be, the results of cases on the ground depend heavily on the instructions given to the jury (we discuss the importance of jury instructions, especially model jury instructions, in FRAND cases in Jorge L. Contreras & Michael A. Eixenberger, Model Jury Instructions for Reasonable Royalty Patent Damages, 57 Jurimetrics J. 1 (2016) (“if … increasingly complex damages calculations are to remain in the hands of the jury, it is now more essential than ever that the instructions given to jurors be as clear, accurate, and understandable as possible.”)

The French Connection

In considering HTC’s proposed jury instruction on apportionment, Judge Elrod also concluded that the proposed instruction was inaccurate because it summarized U.S. patent law with no reference to French contract law. ETSI was formed in France in 1988 and approved its first patent policy in 1993. That policy, and all subsequent ETSI policies, state that they are governed by the laws of France. Judge Elrod observed that “HTC’s proposed jury instructions are based on United States patent law. HTC did not even attempt to justify its proposed instructions under French contract law or to argue that French contract law and United States patent law are equivalent” (slip op. *14).

This last point is particularly interesting. In chastising HTC for failing to argue the equivalency of U.S. and French law, Judge Elrod refers to Apple v. Motorola, 886 F. Supp. 2d 1061, 1081 (W.D. Wis. 2012), in which a U.S. district court seemingly concluded, without any specific references, that there are no material differences between the laws of France and Wisconsin when it comes to interpreting a company’s FRAND commitment (discussed here at p.8). In my experience that conclusion is widely ridiculed by European lawyers, and rightly so. Yet Judge Elrod seems to imply that merely making a conclusory statement about the equivalency of French and U.S. law ought to suffice, or at least overcome one hurdle to the acceptance of a jury instruction grounded in principles of U.S. law.

Nondiscrimination

HTC also argued that the district court should have instructed the jury with respect to the nondiscrimination prong of Ericsson’s FRAND commitment. HTC’s proposed jury instruction reads as follows (Appellant’s Opening Brief, p. 40):

The non-discrimination requirement of FRAND requires an SEP holder to provide similar licensing terms to licensees that are similarly situated. The financial terms do not have to be precisely identical, because the difference might be explained by other offsetting adjustments in other terms in the license. But, at a minimum, if the difference in terms creates a competitive disadvantage for a prospective licensee, then the offered royalty terms are discriminatory. Discrimination may exist even if preferential treatment is accorded to only one or a few companies.

The non-discrimination prong of FRAND serves to level the playing field among competitors, and to foster entry and innovation from new market participants, by prohibiting preferential treatment that imposes different costs to different competitors. Thus, for purposes of the non-discrimination prong of FRAND, licensees are “similarly situated” if they compete for the purchase or sale of a product or service. It would defeat the purpose of FRAND if a licensor could draw a distinction between entrenched and emerging firms.

To my eye, this is an accurate statement of the law and the general understanding of the nondiscrimination requirement under FRAND (see Jorge L. Contreras & Anne Layne-Farrar, Non-Discrimination and FRAND Commitments in Cambridge Handbook of Technical Standardization Law: Competition, Antitrust, and Patents, Ch. 12 (Jorge L. Contreras, ed., 2017)). This formulation is also consistent with the most extensive analysis to-date of FRAND nondiscrimination by a U.S. district court (TCL v. Ericsson, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 214003 (C.D. Cal. 2017), rev’d on other grounds, 943 F.3d 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2019)).

Yet Judge Elrod writes that “HTC’s proposed instruction would transform the non-discrimination element of FRAND into a most-favored-licensee approach, which would require Ericsson to provide identical licensing terms to all prospective licensees” (slip op. *16). This statement is plainly incorrect. The first sentence of HTC’s proposed jury instruction, which mirrors the model instruction published by the Federal Circuit Bar Association in 2020 and cited by the court (slip op. *17 n.3), refers to “similar licensing terms [for] licensees that are similarly situated”, not identical licensing terms for all prospective licensees. HTC further clarifies that “The financial terms do not have to be precisely identical.” In explaining the meaning of “similarly situated”, HTC follows the reasoning of the district court in TCL, stating that a distinction should not be drawn between “entrenched and emerging firms”. None of this suggests that all licensees should pay identical royalties.

Moreover, the parties clearly disputed at trial whether various “comparable” licensees identified by Ericsson were “similarly situated” to HTC (“HTC further argued that Ericsson’s licenses with companies like Apple, Samsung, and Huawei were much more favorable, but Ericsson presented additional evidence indicating that those companies were not similarly situated to HTC due to a variety of factors” (slip op. *22)). Thus, both parties appear to acknowledge the relevance of the “similarly situated” test for nondiscrimination, making it all the more puzzling why the district court and the Fifth Circuit found HTC’s proposed jury instruction on this point to be inaccurate.

Conclusion

Regrettably, the Fifth Circuit’s decision in HTC v. Ericsson does little to clarify the scope or nature of FRAND commitments for standards-essential patents. Rather, by diverging from the guidance of the Federal Circuit in terms of the apportionment of value among patented and unpatented products, and misinterpreting the scope of the nondiscrimination prong of the FRAND commitment, the Fifth Circuit has substantially muddied the already turgid waters of this increasingly important area of law. Unfortunately, Judge Gilstrap was right when he told the jury in Texas, “Ladies and gentlemen, there is no fixed or required methodology for setting or calculating the terms of a FRAND license rate.” It might be helpful to the industry, however, if there were.