Guest Post by Saurabh Vishnubhakat, Associate Professor of Law and Associate Professor of Engineering, Texas A&M University. This post is based on a new paper forthcoming in the Seton Hall Law Review. Read the draft at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2992807.

We tend to think of the different patentability requirements as separate hurdles to be cleared. To be patentable, an invention must reflect eligible subject matter (§ 101). It must be new (§ 102), nonobvious (§ 103), adequately disclosed (§ 112), and so on. A quick review of patent doctrine makes it clear, however, that patent law’s separate statutory requirements reflect similar, overlapping concerns.

Subject-matter eligibility, in fact, overlaps with all the other major requirements. For example, one way to understand why natural products and natural laws are ineligible for patenting is that they are not truly innovative. The concern about innovation is one that the novelty and nonobviousness doctrines also share. Similarly, one way to understand why abstract ideas are ineligible is that the patentee might preempt the full scope of an idea without disclosing all possible instantiations of the idea. The concern about preemption and proportional patent scope is one that the enablement and written description doctrines also share.

Given this overlap, subject-matter eligibility could theoretically be used in place of various other patentability requirements.

How These Overlaps Show Up in Examination

As it turns out, this is not just a theoretical possibility. Evidence for these overlaps is pronounced in actual patent examination. Because compact prosecution pushes examiners to identify all grounds for rejection together (rather than raise them piecemeal across multiple Office actions), it is possible to learn how frequently a given invention presents multiple patentability problems.

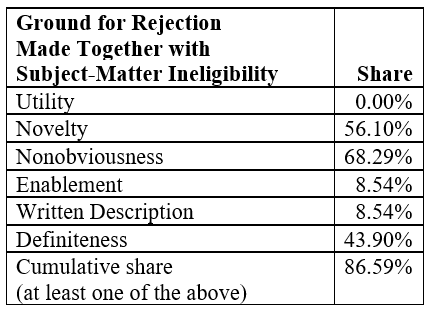

A new, fairly large dataset (800 randomly selected patents) of USPTO records reveals that subject-matter ineligibility does overlap substantially with other statutory requirements in examiner Office actions. More than six times out of seven, an invention that was rejected for ineligibility under Section 101 was also rejected on at least one other ground.

How These Overlaps Show Up in Litigation

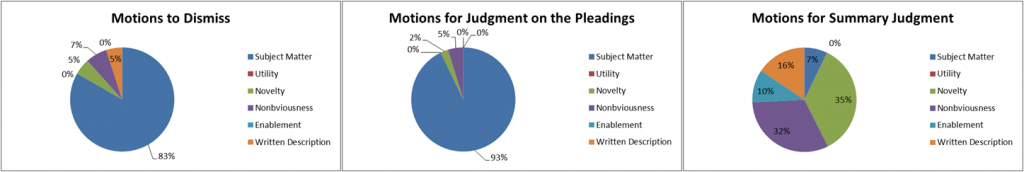

These overlaps have also become very interesting to courts because they seem to offer a shortcut for deciding patent validity more quickly and more cheaply: by using subject-matter ineligibility at the pleading stage. Litigation data on motion practice in patent cases bears this out. Early in litigation, when decision costs have not yet accrued, motions to dismiss and motions for judgment on the pleadings are based primarily on ineligibility under Section 101. By contrast, among motions for summary judgment following discovery, subject-matter ineligibility plays a much smaller role as other, more fact-intensive patentability doctrines can now be argued.

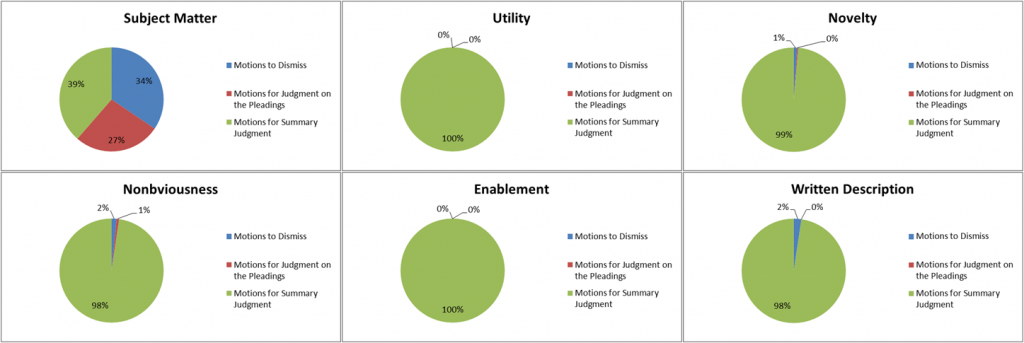

Conversely, the points at which subject-matter ineligibility is argued are spread fairly evenly across motions to dismiss (34%), motions for judgment on the pleadings (27%), and summary judgment (39%). The five other major patentability requirements—utility, novelty, nonobviousness, enablement, and written description—come up almost exclusively at summary judgment.

Why Courts Like Section 101 As a Shortcut—and Why It’s a Problem

Using subject-matter eligibility early can be attractive to a court. Deciding a patent’s validity at all can be costly. Claim construction, discovery, jury trials—the list of decision costs goes on. Deciding validity incorrectly can be costly, too. Failing to strike down an invalid patent tends to distort the market today and enable abuses such as nuisance litigation. Meanwhile, wrongly striking down a valid patent tends to undermine incentives for future investment in research and commercialization.

A court that invests more resources in a decision is less likely to make a mistake, but this only helps to a point. If the next dollar spent on reaching a good decision saves less than a dollar of error cost, the overall expenditure is actually a waste. The lesson, then, is not to minimize decision cost alone or minimize error cost alone but to minimize the sum of decision cost and error cost. (This insight is at least as old as Judge Frank Easterbrook’s 1984 paper on decision and error in antitrust cases.)

Problems arise in the patent context when judges who want to conserve resources today cut too many corners and underestimate their likelihood of errors. The costs from those errors, after all, lie in the future and are easy to miss. Judges in patent cases have begun relying on a style of decision-making that is quite similar to antitrust law’s distinction between per se rules and the rule of reason.

An antitrust rule that says a certain economic practice is per se invalid is cheap to administer but, like many bright-line rules, can lead to errors. The rule of reason is more likely to result in a correct decision about the economic conduct in question, but will require more judicial resources. Per se rules of antitrust should only be used, therefore, for types of economic conduct that are well-understood and very reliably harmful.

Subject-matter eligibility is becoming a sort of per se shortcut for patent invalidity, in contrast to more costly inquiries like nonobviousness or enablement analogous to the rule of reason. The historical lesson of antitrust, though, has been that per se rules should be used very sparingly because a wide range of economic practices may prove to have procompetitive effects. This does not mean the conduct is definitively legal under the antitrust laws—or that a given patent is definitively valid. It simply means that more information and more careful judicial consideration are needed before an accurate decision can be reached.

Until now, the use of subject-matter eligibility at the pleading stage may be conserving decision costs, but without sufficient regard for error costs in decisions on patent validity. In my paper, I discuss problems with the current approach and propose three ways to guard against this irresponsible borrowing from antitrust.

With respect, some of the author’s premises are simply incorrect. Unfortunately, they represent the current status of an inordinate amount of poor jurisprudence from the Supreme and Federal Court regarding subject matter eligibility.

“Subject-matter eligibility, in fact, overlaps with all the other major requirements.”

Nope, that is why the statutes are codified into separate sections to address issues separately.

“For example, one way to understand why natural products and natural laws are ineligible for patenting is that they are not truly innovative. The concern about innovation is one that the novelty and nonobviousness doctrines also share.”

Nope, 101 subject matter eligibility is not about novelty and nonobviousness. It is about whether or not the subject matter fits within certain categories. 102 and 103 deal separately with novelty and nonobviousness. Judicial exception to subject matter eligilibility aside, unmodified natural products should not patentable (regardless of whether they are subject matter eligible) because they already existed before human intervention. Modified natural products are no longer natural products per se and should be patentable. Natural laws are not subject matter eligible because they are intangible and existed in nature before human recognition thereof.

“Similarly, one way to understand why abstract ideas are ineligible is that the patentee might preempt the full scope of an idea without disclosing all possible instantiations of the idea. The concern about preemption and proportional patent scope is one that the enablement and written description doctrines also share.”

Nope. Abstract ideas are ineligible because they are intangible. Enablement and written description (both of which are 112) have nothing to do with preemption but they are material to supporting claimed scope of coverage.

Similarly, one way to understand why abstract ideas are ineligible is that the patentee might preempt the full scope of an idea without disclosing all possible instantiations of the idea. The concern about preemption and proportional patent scope is one that the enablement and written description doctrines also share

Do not have time or stomach for reading all the comments here so sorry if someone pointed this out already BUT – this is the kind of data that while interesting should be presented to Congress not courts.

Congress made the law into discrete sections, it should be interpreted as discreet sections if they wanted a more holistic analysis they certainly could have set it up that way. They did not.

The supreme court incorrectly confused 102 and 103 into 101 – they should not have done so.

Daniel Walker Cole, is material found in nature “new” even if it was unknown to man?

Ned,

We both know that Congress defines what “new” means.

And we both know that in the AIA, Congress has defined “new” to be “new to you.”

You ask a series of questions, to which answers and discussions – with you – have been started, but from which you have retreated and stopped the dialogue.

By starting these questions up anew – without reflecting the counter points already put to you, you are engaging in the internet style of Shouting Down.

DWC is quite clearly new to the blog. Please engage with some inte11ectual honesty by NOT presenting merely the starting points of past dialogues (especially when you are quite aware that the rejoinders you leave out are material).

Anon, what we “both” know is not the same. The common law defines “new” unless Congress unambiguously changes it. “New” has been in the statutes since 1624 – the Statute of Monopolies. At the same time, the requirement that the invention not be used by others or the invention of another has also been in the statutes.

If “new” and “not used by others” and “not invented by others” is meant to be the same thing, then why has it been different in the statutes for 400 years?

Daniel Walker Cole, is the typewriter new words change?

Should read, “Is the typewriter new when the words change?”

Dialogues pieces inexplicably remaining blocked:

To Ben at 14.2:

August 11, 2017 at 1:02 pm

Ben,

Except when the used prior art is not a subset, but rather is merely an analogous set.

It is particularly the cases in which the rejection under 101 is for an application claim that has a tighter scope than the patented item to which my views originated from.

To Ned at 13.1:

August 10, 2017 at 4:42 pm

“that are not themselves purely functional”

What does “purely functional” mean to you Ned.

More importantly, what does that term mean as to patent law?

I ask because many times and in most all circumstances upon which we comment here, the term coined by Prof. Crouch is simply more accurate.

That term of course is: Vast Middle Ground.

As I have on numerous occasions pointed out, the tendency to label ANY use of functional language in a claim as necessarily being controlled by 112(f) is simply a fallacy, and an inaccurate presentation both of the issue, and of the controlling law as relates to that issue (including what commentators of the Act of 1952 has to say about Congress’s actions – notably including Federico).

That Vast Middle Ground – as opposed to any notion of “purely functional claiming” is also something that you tend to obscure (purposefully or otherwise) when you lean back to your penchant of “Point of Novelty.”

If by “purely functionally claiming” you are already parsing claims down to words that are functional separate from any present elements, then you have improperly attempted to apply that same “Point of Novelty” to a 101 type of analysis that disregards what the law actually is.

As you might have gathered by now, this is NOT ONLY in combination claims that this tendency of yours to parse and improperly apply 101 surfaces. Yes, any single (non-combination) claim has inherent difficulties, and yes, combination claims were broadly liberalized by Congress in 1952. But there still remains the obfuscation that so often happens when “purely functional claiming” is a label applied to claims merely containing functional language.

and Ned at 6.2:

August 9, 2017 at 5:12 pm

“That leaves “abstraction” as a word-substitute for business method,”

Your windmill is showing, Ned.

To Malcolm at 12.1:

August 10, 2017 at 4:46 pm

“to carry out logic”

Malcolm, please stop peddling your fallacies.

“All these things are old and admittedly old”

You are doing that Big Box of Protons, Neutrons and Electrons thing again.

Each of these subatomic particles are old and admittedly old. And yet, configurations of the old are eminently patent eligible. Leastwise, are not per se patent ineligible – as you would have your anti-software patent views be held.

Your argument does not – and never has – properly reconciled this counter point. Just because you attempt to say the same thing over and again does not make that counter point disappear.

To Alex at 7.1.1.1.1.1.1:

August 10, 2017 at 4:50 pm

Alex.

Do not confuse an examiner wrongly applying the law with what the law actually is.

August 10, 2017 at 4:52 pm

Further,

The “machine itself” prong is wrong per Bilski which rejects the Machine or Transformation prong as a legal requirement (and what is being attempted is requiring the machine prong).

And Alex at 7.1.1.2.2.2:

August 10, 2017 at 4:53 pm

“Software operations can be performed by thoughts alone”

The thought of software is not software.

There are ZERO machines currently available that run on thoughts.

To I invented that at 14.1.2.1:

August 10, 2017 at 4:31 pm

Thank you, Iit.

The distinction you offer of something not being a patent in order to still be a reference is a cogent counter point to my supposition.

That being said, I withdraw the proposition.

To AIGC, Inc. at 3.1.3.1.1.3.1:

August 9, 2017 at 5:15 pm

Stevens does not the law make.

No matter how hard he tried.

(and that is why he lost his majority writing position on Bilski).

and AIGC Inc. at 1.1.1.1.1.1:

August 9, 2017 at 5:18 pm

He is using it. That necessarily implies that it is a valid reference TO use.

And THAT necessarily carries with it the presumption of validity under 101.

[note that I subsequently stepped back from the one to one tie that had prompted this comment]

anon, purely functional is a term that describes an apparatus in terms of the results it achieves or the way it achieves those results rather than in terms of its structure.

That said, I think it is legitimate to describe software in terms of steps.

No Ned.

What you describe may range the gamut from functional to purely functional.

You appear to either NOT know of which youowant to talk about, or you still are pretending to not know that which you are talking about.

Let’s try a different angle.

What do you think the term “Vast Middle Ground” means?

But anon, Ned is right: abstraction is a word-substitute for business method, math or the like. “The problem with such subject matter is that they are not machines, manufacture, or compositions a process involving the making or the use of such to produce a new or improved result.” This is how the PTO currently operates; you may ask your friend “6”.

Bluto is also right and “examiner argument” is elevated to replace factual proof. The law is only as good as it can be enforced; for example, is the best mode requirement the current law? Remember, those examiners and SPEs are only interested in golfing (see Washington Post), cannot be fired and are free to ignore the law such as the APA or Bilski, McRO, etc.

In fact, McRO was just a Fed.Cir. opinion; how many examiners in 36xx are bound by it if they routinely ignore decisions such as Bilski and just make up stuff in general?

Do not confuse a broken scoreboard with “Ned is right.”

Ned’s “logic” is supported by lobbyists such as EFF, the PTO and the Federal Circuit (for example, a precedential decision in RecogniCorp, LLC v. Nintendo Co., Ltd. (2016-1499)). The Congress and SCOTUS are ok with the status quo, so the highest authority on this matter is with the Fed.Cir. And if you are unhappy with Judge Reyna, then we can ask our friend Haldane Robert Mayer to see his view on the patentability of business and software methods.

So, yeah, Ned IS right.

If you really believe that, then why do you still fight?

Or do you think that broadcasting such a “why bother” message is somehow not fighting for those that defeated you?

Dear anon, for some reason my posting did not go through.

Why “broadcasting”:

– to see whether the position of the office (lying, refusing to provide supporting evidence, misinterpretation of statutory and case laws) is “normal”. From what I’ve read on this site, it is not unusual. And, short of appealing to the Fed. Cir., no one can MAKE the office to show real evidence: my basis for this statement are other (work) patent applications, filed by national IP firms.

– maybe pick up some pointers for my position.

– and yes, maybe somebody can learn from my experience.

Why “still fighting”:

– I invested too much of my time, efforts and money to let it go.

– Still have a free shot with 37 CFR Section 1.181 to remove final, since the Examiner suddenly and without warning changed the abstract idea in the Final Rejection. Yes, I know that the probability is low.

– Want to try one last time by appealing. Perhaps PTAB judges are more honest and law-abiding than examiners.

I never expected to read all SCOTUS and Fed.Cir. cases related to 101, and I have a nagging suspicion that my efforts would be better spent some place else, such as learning a new area at work. But it is what it is. And I am still considering a parting shot, if everything else fails, to describe this mess in a national newspaper.

You seem to be very knowledgeable in this area, so do you honestly believe that I have any other way to proceed at this moment? Generally, I wonder if you believe that anybody can get a patent in TC 36xx?

And let me ask you the same question: why are YOU fighting? You’ve been arguing with MM and others on this site for years, and it did not sway any of your opponent at all. So why fight?

We may both have this unhealthy belief that the good will always prevail in the end. Kind of like fairy tales …

Thanks,

-Alex

Alex,

I hear what you are saying (moreso than most, as I have done a little digging into your records), but you are not grasping my comment vis a vis the style of your “broadcasting.”

The “throw up the hands and ‘they must be right’ attitude” style, while you may intend to be more tongue in cheek, WILL BE taken at its face value by FAR too many that won’t take the time to realize that you mean the opposite.

That “style” is far TOO prone to merely prod the lemmings to march faster up their hill. When engaging with those who appeal to people to NOT think critically, it is simply much more clear to be much more direct.

As to your asking of the same question of me: I am fascinated by the rule of law, have a deep and abiding interest in a STRONG patent system (having more than just a passing background in innovation history), and am appalled at what passes as “critical thinking” of the opponents seeking weak (or non-existent) patent rights. At the same time, the view of human frailties, including some not so unfamiliar dystopian fears (including the persistence and even effectiveness of propaganda) play out in the ongoing patent drama, and I do not know of very many areas of law that is so “alive” with countervailing forces and a battle to shape an area of law that patent law is now experiencing.

So why fight? Losing only truly comes when one capitulates. While the Keynesian Long View does hew to the maxim: “In the long term, everyone has died,” the journey and the battles along the way define who you are.

Ah, I get it: you are interested as much in the journey as in the destination. And I like your style: you have quite a way with the words.

Me, I just want a fair examination of my application. I’m not a lawyer or an IP pro: my background is computers and economics. And I am also appalled at the current mess in the patent system and total disregard for the laws.

May I ask you for one last favor? I’m very curious about what you meant by saying that there is a way to make the Office to provide evidence. I’ve tried talking to the Examiner (including, I’m ashamed to say, a little kiss-ass approach), SPE, TC director and emailing Michelle when she was in power. I’ve also tried contacting USPTO legal department (short/predictable reply: we are committed to comply with all applicable laws) and filing requests under 37 C.F.R. 1.104 (ignored). Did I miss something?

The rule of law does not exist in the PTO: SPE refused in writing to even discuss anything related to the APA. However, I did manage to make the force the PTO to do something. From the FOA: “Examiner fails to understand how any of the claim’s functions occur and must rely on Applicants disclosure which is only directed to generic computer functions as stated above.” and “Examiner is FORCED to consult the specification to understand how applicant’s claims to “electronically delivered merchant gift cards” and “electronic coupons” and enrolling a user with an internet enable electronic device can be performed.” She could not understand the claims but then: “Upon further investigation into the specification, Examiner finds generic computing functioning in paragraphs [0009] smartphone application; [0056] an interface such as website, …” Finding some computer functionality in the spec made her all warm and fuzzy, because she could now use the trusted rejection form.

Interestingly, in the prior OA, she was downright giddy after finding a “processor” mentioned in the spec. I mean, this is a processor, that can be programmed and rejected, right? And then, her happiness came to an end when I pointed out that the “processor” was a payment processor, defined in the spec as an entity such as bank. She was very upset: “As the Applicant has expressly stated that there are no claims to the processor stated in the specification containing computing functions, and has not claimed anything more than generic computing function to implement the idea, Examiner concludes that the method claims can be performed by human thought and by a human using pen and paper.”

Yep, these people do not read the spec, they just search for keywords. Remember the ending of an old joke? “The Government Worker called to his dog and said, ‘Coffee Break, do your stuff!!’ Coffee Break jumped to his feet, ate all the cookies, drank the milk, pooped on the paper, sexually assaulted the other three dogs, claimed he injured his back while doing so, filed a grievance report for unsafe working conditions, put in for worker’s compensation, and went home for the rest of the day on sick leave.”

Thanks,

-Alex

Alex, see 104(c)(2) for the rule that requires the examiner to support unsupported statements with evidence.

Thank you Ned. As I mentioned before, I used 104(d)(2) which was ignored: “(2) When a rejection in an application is based on facts within the personal knowledge of an employee of the Office, the data shall be as specific as possible, and the reference must be supported, when called for by the applicant, by the affidavit of such employee, and such affidavit shall be subject to contradiction or explanation by the affidavits of the applicant and other persons.”

Thanks,

-Alex

Functional, anon, is when the machine, manufacture or composition is described in terms of what it does; or a process in terms of the results achieved.

NOT the question I asked Ned.

Try again.

Purely functional versus Vast Middle Ground.

Buried down below, there is an exchange of which I would be interested in hearing from the usual examiner “cohorts”

Is an assertion on the record as regards 102/103 a defacto admission as to 101?

From below:

1.1.1.1.1

AIGC, Inc.

August 8, 2017 at 9:44 pm

I agree that a claim definitely can fail multiple statutes simultaneously such as 101 and 112. But, how about the claim simultaneously failing 101 when rejected under 102? For instance, when an Examiner rejects a claim under 102, the Examiner is basically finding that the claim does not include any inventive concept whatsoever. So, should the claim also fail 101 at that point as well?

And, when the applicant amends the claim in response to a 102 or 103 rejection, should the Examiner consider the amendment(s) to be the purported inventive concept and run through the Alice two step again?

I guess my point is that I can see a claim going from patent-eligible to patent-ineligible when new prior art is found and applied since the novelty and inventive concept will change based on what was known.

1.1.1.1.1

anon

August 9, 2017 at 7:01 am

AIGC, Inc,

Yes, you bring up a valid point with the examination protocol of multiply rejecting items.

When an examiner bases a rejection on 102/103 with the use of a cited reference that is a patent, by law that cited reference is presumed valid – which, as anyone noting the “overlap” would (if they be honest) tell you that THAT also means that the examiner believes the valid patent reference must also pass 101.

Quite frankly, what is happening in the examination phase when an examiner uses a combination rejection is that the examiner is nullifying the validity/eligibility of a granted patent against what the law provides. If the examiner truly believes that such a 102 or 103 rejection is proper (and their submitting such to you in an official action says just that), then THAT is an admission by the Office that 101 is improper.

One can fight the 102/103 reference suitability quite apart from pointing out to the Office that they TOO are bound by their prosecution assertions that are part of the written record.

I don’t really even know what you mean to be asking anon. You guys make 101 too difficult when it isn’t difficult. Nor will the office be “bound” by prior statements, it is up to the office to be “up to date” in its determination at the time of any action being taken, and also to correct for any prior mistakes.

Further, when an amendment is made the office must look at the claim as a whole for 101 purposes, not merely the amended part (although that might be the main focus of where they have to look in a given claim depending on the claim).

I don’t really even know what he means to be asking either.

Can your “and also to correct for any prior mistakes.” include a de facto nullification of a patent that has NOT been adjudicated (by anyone, even less an Article III court) to have failed 101, when that patent – by law – carries with it a presumption of validity?

When an examiner uses prior art to reject under 102/103 (as well as 101), and that SAME prior art must be deemed valid – which includes valid under 101 – the Office is presenting a self-conflicting statement.

The Office cannot have it both ways. The item is either not proper art citable for 102/103 or the present rejection under 101 is not proper. By stating that the cited reference is proper for an (attempted) 102/103 rejection, the Office is ALSO stating that the “directed to gist” of the present invention – as it so relates to the cited art which is valid – must ALSO be valid insofar as 101. Perhaps, unstated, but BOTH the cited prior art and the present item under examination rise and fall together for 101 purposes.

My point has nothing to so with any “look at the amendment” or any notion of not looking at the claim as a whole, so I have no response to those portions of your reply.

Anon, I think you are off track here, although I agree with you on most of your views on 101. A reference under 102/103 need not be patent eligible under 101, since the reference need not be a patent. Somewhat related, a reference under 102/103 need not be as fully enabled under 112 as the subject application. This is referred to as “enablement light”.

replies still being held in the “don’t have an actual dialogue” filter…..

Test

My dear anon, the mystery of anon/Anon may never be solved. That is because it stands for anonymous and any superficial similarities between the two are only designed to further confuse – sort of like 101 decisions. 🙂

AlexO,

I think that you may be onto something.

anon/Anon stands for anonymous, so I guess that instead of being concerned with just who is saying something, the better path is to pay attention to what is being said.

😉

Thank you for a good advice. Unfortunately, nothing that is being said here really affects the reality. I understand that the purpose of your discussions with MM/6/etc. is to find out the right approach through reasoning and logic, but the facts are:

– SCOTUS said that the exception was there for more than 100 years, yet it was not codified into the law in 1952;

– Neither the PTO nor the Federal Circuit require any evidence to support rejections. Therefore, the result of every examination and Court case depends on a whim of the examiner or which panel is deciding the case;

– The laws matter only when they are enforced. I was born and raised in the former Soviet Union and it had many very good laws, some of them better that what we have now in the US. The devil was in their interpretation/execution/enforcement;

– Even a child can invalidate any application: “It is directed to an abstract idea of . All additional claim elements are well-known, conventional and routine, and do not amount to significantly more. Therefore, the claims are directed to an ineligible subject matter.” No proof of any kind is required; if requested, the Examiner simply repeats the rejection. RCE fees for applicant, golfing for the examiner.

– Examiners simply don’t consider Fed.Cir. cases that affirm patent eligibility as valid; they simply ignore them or say that they are directed to a different subject matter. On the other hand, they embrace all cases that affirm patent eligibility.

The ONLY reason why people don’t come with torches and pitchforks to take care of these things is because the vast majority of them are not affected at all by patents and don’t care one way or another. This is a playing field of large corporations and their lawyers. I found out that I cannot even sue an examiner for lying.

Thanks,

-Alex

AlexO,

The scoreboard is broken. The point of these discussions is (in part) to illuminate the fact that the scoreboard is broken so that people do not pretend that the broken scoreboard is reflecting reality.

Reality is quite different than the broken scoreboard.

Depending then on thinking that SCOTUS “must be correct” is very much part of the problem.

As to your comment pertaining to “require any evidence,” notwithstanding your sorted details of personal interaction (and this is where having professional assistance would likely have helped you), one CAN make the Office provide sufficient real evidence.

One does not get to that point though with thousands of pages of ill-directed (mind, you, I am not saying ill-conceived) arguments.

And yes, I too** have checked into your plight. I see where your “they must be right” attitude is coming from, although I think we both still realize that they are in fact not right.

**just like that Capital A guy. 😉

Mr. “6”, you are wrong: it is not just easy, it is super-easy. All you have to do is to find any computer element in claims or specification to make a 101 rejection. And you don’t even need to understand the claims to do this. Didn’t you go through the training at the PTO?

A claim directed to a judicial exception usually defines a scope which also includes eligible inventions. When prior art is applied against the claim under 102/103, it is applied to a valid subset of the claim’s scope. Thus there is no implication regarding whether the prior art is directed to a judicial exception.

This statement is directed to the guidelines and case law that involve determinations of whether the claim recites things that are “well-understood, common, ordinary.” Claims can be found ineligible under 101 when all elements and the claim as a whole is known in the art or “well-understood.”

In the context of 101: the Office has the right to adjudicate that a claim includes only well-understood limitations and that the claim as a whole also does not have “something more.” The Office does not have to provide any evidence, other than Examiner argument, that the claim limitations are “well known.”

What anon is saying is that if a claim is “anticipated” meaning all claim elements are well-understood or known in the art, that the claim should simultaneously fail under 101 for being ineligible. Again, this is permissible based on the fact that many of the work around test(s) used by the USPTO for determining eligibility stray so far outside the intended bounds of the statute and wander into other provisions of the statute.

Cool, no checks and balances! Like taking a candy from a child: say that all claim limitations are “well known”, then off to golf. Can the PTO patent this algorithm?

Bluto,

I have to wonder if you mistated my view to the extreme in order to point out the innate illogic of the result?

(Your attempt to have “examiner argument” elevated to replace factual proof is strict legal error)

It would be helpful to identify the technologies at issue in the cases you analyzed. Much of the discussion about Section 101 eligibility has involved issued software patents, which tend to focus on the “inventive concept” requirement in the Supreme Court’s Alice decision. Rather than interpreting the term “new” as a shortcut for Section 102′ novelty requirement, which is well defined, the Supreme Court decided that an abstract idea used in a computer program may be patent eligible if the invention incorporates something new, an undefined inventive concept. However, even if the invention is determined to be patent eligible, it can be invalidated (or the application can be rejected) if it fails to satisfy Section 102.

It would also be helpful to include statistics on the Federal Circuit’s review of cases that are dismissed on the pleadings or failure to state a claim. While such decisions may serve judicial economy in unreasonably filed cases, they can lead to greater expense and effort for the parties and the courts if the decisions are reversed. As an expedient alternative to discovery, motions, claim construction hearings and trials, such dismissals tend to disserve the patent system and the courts by denying a patentee the incentives that the Constitution provides for inventors and the opportunity to protect those incentives through the judicial system. Even if a patent is ultimately held to be invalid, the patentee, like every person, is entitled to prove his or her case (dismissals on the pleadings are decided without procedures for claim construction) if it satisfies Rule 11 and not brought for an improper purpose.

Jai, excellent points. It does illustrate confusion caused by applying Morse, which involves overbreadth, to the question of whether the subject matter is within the four classes.

I would remark that if a combination claim is involved, that Congress has statutorily overruled Morse/Halliburton in section 112(f). There can be no overbreadth provided there is corresponding structure, materials and acts described in the specification that are not themselves purely functional.

I think this post has things backwards. If you apply 102, 103, 112 in an honest and objective way, you don’t need the Alice construct of 101. It’s not just that there’s overlap, it’s that Alice was just plain wrong. Now we receive rejections that do not cite any prior art whatsoever, yet declare things as being well known. Yes, exclusive 101 rejections – this is where we are at.

Computers, programmable computers, databases, networked computers, the Internet, programming computers to carry out logic, using multiple computers to carry out different tasks, portable computing devices, the fact that you can use computers to carry out logic on data in any context, the fact that computers don’t care about content, etc etc [massive additional items that could be listed are omitted here to save space and avoid insulting the intelligence of the grown ups in the room]

All these things are old and admittedly old (either expressly admitted or implicitly admitted) in 99.99% of the junky “do it on a computer” patents out there. If you need “prior art” cited to prove these basic facts in 2017, you don’t belong anywhere near the patent system (but we knew that already).

Malcolm, these computer-related things don’t even need to be claimed. Mentioning them is the specification should be enough to throw away such patent.

There is oil under your house. Nobody knew there was oil under your house before. Drilling for oil is known. I discover the nature fact that there is oil under your house, and claim drilling for oil under your house. The claim has utility, as it results in oil. It is enabled, possessed, definite. The act is non-obvious because the location of the oil was not something previously known to the public.

Do you need the Alice construct of 101?

“The act is non-obvious because the location of the oil was not something previously known to the public.”

Not sure that flies.

That’s Sequenom. Instead of gold, its fetal DNA; instead of under the house, it’s in maternal plasma.

Yet people fail to understand why that information, alone, can’t make a patent.

You are still operating under the confusion injected by those wanting to follow a broken scoreboard.

Information alone is not being stated as “making a patent.”

NO ONE is proposing that position.

(I think that you are getting stuck in a dissected view of a claim)

Well, of course. The problem is that 102/102/112 were not being properly applied, and most of the “experts” denied this was the case. Then the non-engineers at the Fed Cir and SCOTUS had to develop a standard that actually worked. Therefore, the new 101 was born.

Alex in Chicago: “the non-engineers at the Fed Cir and SCOTUS had to develop a standard that actually worked”. So, what is a standard for an abstract idea?

Random, your interpretation is not to be discounted. I still read that the problem was the apparent scope, not the actual scope, because the lower courts did in fact construe the claim per Westinghouse to cover the mechanical tuner, and found the electronic turner to be an equivalent.

Regardless, post ’52, the real scope of MPF is narrow, but the apparent breadth is very broad. Such claims do not particularly point out the invention within their four corners, albeit they might after construction in a court of law — but certainly not when they issue from the PTO.

Halliburton was not mentioned in Nautilus. Nautilus relied on United Carbon and Wabash appliance — claims not involving combinations and thus not subject to 112(f) and a narrowing construction.

To support my view, consider:

“The language of the claim thus describes this most crucial element in the “new” combination in terms of what it will do rather than in terms of its own physical characteristics or its arrangement in the new combination apparatus. We have held that a claim with such a description of a product is invalid as a violation of Rev. Stat. 4888. Holland Furniture Co. v. Perkins Glue Co., 277 U.S. 245, 256-57; General Electric Co. v. Wabash Appliance Corp., supra. We understand that the Circuit Court of Appeals held that the same rigid standards of description required for product claims is not required for a combination patent embodying old elements only. We have a different view.”

H. at 9. Couple that with,

“Under these circumstances the broadness, ambiguity, and overhanging threat of the functional claim of Walker become apparent. What he claimed in the court below and what he claims here is that his patent bars anyone from using in an oil well any device heretofore or hereafter invented which combined with the Lehr and Wyatt machine performs the function of clearly and distinctly catching and recording echoes from tubing joints with regularity. Just how many different devices there are of various kinds and characters which would serve to emphasize these echoes, we do not know. The Halliburton device, alleged to infringe, employs an electric filter for this purpose. In this age of technological development there may be many other devices beyond our present information or indeed our imagination which will perform that function and yet fit these claims. And unless frightened from the course of experimentation by broad functional claims like these, inventive genius may evolve many more devices to accomplish the same purpose. See United Carbon Co. v. Binney & Smith Co., 317 U.S. 228, 236; Burr v. Duryee, 1 Wall. 531, 568; O’Reilly v. Morse, 15 How. 62, 112-13. Yet if Walker’s blanket claims be valid, no device to clarify echo waves, now known or hereafter invented, whether the device be an actual equivalent of Walker’s ingredient or not, could be used in a combination such as this, during the life of Walker’s patent.

13*13 Had Walker accurately described the machine he claims to have invented, he would have had no such broad rights to bar the use of all devices now or hereafter known which could accent waves. For had he accurately described the resonator together with the Lehr and Wyatt apparatus, and sued for infringement, charging the use of something else used in combination to accent the waves, the alleged infringer could have prevailed if the substituted device (1) performed a substantially different function; (2) was not known at the date of Walker’s patent as a proper substitute for the resonator; or (3) had been actually invented after the date of the patent.”

H. at 12-13.

We know that the Federal Circuit has implemented items 1-3 of the last paragraph above in its construction of 112(f). But nothing truly addresses the broad overhanging threat issue. Nothing.

But nothing truly addresses the broad overhanging threat issue. Nothing.

That’s only true if you buy the CAFC logic (which I agree is the current law) that breadth cannot be indefiniteness. Nautilus seems to say that vagueries for the purpose of expanding breadth when reasonable alternatives exist is improper.

Let me put it like this – For me, sitting with BRI, it’s really easy for me to see how the indefiniteness/abstraction dichotomy works: You don’t read in any limitations so either the claim discloses the means or the claim uses vague language to get a superset of the disclosed means. Once that superset is “too super” (e.g. you’ve surpassed equivalents) you’ve passed the point of which your claim language was allowed to be reasonably non-descriptive of your disclosed means, and it fails to “point out and particularly claim” the subject matter from the spec. Conversely, sometimes someone will outright say “Here’s a means, now that I’ve shown you one way of achieving Result X, I invented achieving result X, and my claim to achieving result X particularly describes what I have invented” in which case you’ve got a claim to an abstraction absent concrete limitations.

The two problems come in when you start importing limitations via some sort of BS language construction, as that creates uncertainty as to whether a limitation was meant to be claimed. The second problem is when you ignore the word “particular.” In the CAFC’s view, anything not vague or ambiguous is particular, and the claim scope not fitting the disclosure scope is solely a matter of 112a, which has the problem of forcing someone to counter-invent to reject an overbroad scope (under 112a) and confuses some people about how the “abstraction” part of the indefiniteness/abstraction dichotomy works.

I disagree with Enfish and McRO on their particular facts, but their logic is not wrong: Enfish is basically saying the claim was claiming means not bigger than the equivalents (since it used MPF) and therefore the abstraction test part of the dichotomy is satisfied. McRO similarly claimed (according to them) particular novel means. These are times when the disclosure and the construction were sufficient to allow for the argument “I invented this particular thing and that’s all I’m claiming” rather than an argument that can be characterized as “I invented this thing, and that disclosure supports all things which achieve its result” or “I invented achieving the result”

“that breadth cannot be indefiniteness.”

You have this crabbed.

It is NOT that it cannot be.

It is that it is not necessarily being.

“For me, sitting with BRI, it’s really easy for me to see how the indefiniteness/abstraction dichotomy works”

You are not seeing it correctly – and getting both areas wrong. It is simply NOT the two rung ladder of “dichotomy” that you keep seeing it as.

[P]roblems come in when you start importing limitations via some sort of BS language construction, as that creates uncertainty as to whether a limitation was meant to be claimed.

Exactly.

Which is why when this is permitted, the claims are indefinite.

You lost you case long ago concerning 112 (the one with Stern [?] helping you) and you still have not learned your lesson.

Well of course there’s overlap. If you set up a problem and then claim (using vague or functional language, 112b) all solutions to the problem you’re performing an abstraction (the act of solving rather than a concrete solution, 101) when you don’t possess all of the solution (112a) and you’re probably not the first to provide a solution (102/103).

Contrary to the argument above, the fact that use of poor language and broad claim scope justifies many rejections does not mean it is an end-run or a conflation to dispose of the claim under 101, any more than it is wrong to consider a claim under indefiniteness in an effort to avoid prior art questions.

Random, my posts are being blocked by the filter.

Random, I have a question.

Your:

“If you set up a problem and then claim (using vague or functional language, 112b) all solutions to the problem you’re performing an abstraction (the act of solving rather than a concrete solution,….”

Is that argument something you created, or have you borrowed it from somebody else? I ask because I haven’t seen it before and (from my viewpoint in EPC-land) I like it a lot!

Max, I refer you generally to Boulton & Watt v. Bull, 1 Carp. P. C. 117.

But, how can a principle in the abstract be considered to have been reduced to practice. It is not an invention until it is. It is upon filing if the specification provides a solution to the problem.

…if that specification is enabling…

…and enabling is viewed – as I have long indicated – in the eyes of the Person Having Ordinary Skill In The Art. This. of course, then circles back to the fact that the Supreme Court***, courtesy of such decisions as KSR have evolved that very same Person Having Ordinary Skill In The Art to have “super powers” and be quite different than say, for example, the mere automaton of the Euro version of that legal “person.”

This is like the flip side of our pal Random’s ‘predictable arts’ screen.

***yet another case of what is called “patent profanity,” but a rare one that while intending to work against those who would have patents, has the necessary trailing sword edge of working for those who would have patents, directly feeding that angst of yours of claims with terms sounding in function, and H U G E L Y increasing those claims (fully) in what Prof. Crouch has termed the Vast Middle Ground.

By the way, Ned, I still have not seen your answer as to my question to you on what that term means. Can you contrast that term with your use of the phrase “functional claiming,” or to be more particular, “pure functional claiming”…?

It is almost as if the highest court in the land conflated 101, 102, and 103 to such an extent that it affected agency policy. Really makes you think. Good article Saurabh – important topic.

Yay selective editing – because pointing out the attempted fallacy of “patents on logic” is SOOOOOO “offensive” and all.

La Vee.

The authors: Problems arise in the patent context when judges who want to conserve resources today cut too many corners and underestimate their likelihood of errors.

This pattern isn’t limited to the “patent context”, nor is the behavior limited to “judges.” It is a pattern that tends to occur when a system is overwhelmed and struggling to keep up with a massive recurring problem. That’s what happened to the patent system when it was — without very little forethought — opened up to the patenting of logic and information (directly or indirectly).

The costs from those errors, after all, lie in the future and are easy to miss.

We are dealing with the “costs” from an earlier error which was predicted by many but ignored (or cheered) by people who should have known better. And while the Supreme Court has worked to correct the error, invested parties are working hard to compound it (i.e., by broadening 101 even further, by statute).

Judges in patent cases have begun relying on a style of decision-making that is quite similar to antitrust law’s distinction between per se rules and the rule of reason.

Whether or not this is true, the fact is that judges are reacting to the cases that are brought before them. Fashioning “per se” rules barring certain anticompetitive activities makes perfect sense when those anticompetitive activities are legion and causing systematic problems. Likewise, the frequent use of 101 to quickly tank patents relying on (e.g.) abstractions for novelty makes perfect sense when those patents are overwhelming the system. There is no reason to expect successful motions on the pleadings against patentees to be “rare” when patentees are routinely asserting the worst patents ever granted in the history of humankind against hundreds of businesses in diverse industries. It’s bizarre to conclude otherwise, unless you were born yesterday or you are simply incapable of connecting the simplest pattern of dots imaginable.

I’d also like to address some of the mistaken comments made below about “abstractness”, specifically the erroneoous comment that “abstractness” has “nothing to do with patentability.”

Abstractness often has a lot to do with ineligibility but (like everything else) it depends on the claim. There is. for instance, nothing abstract about a newly discovered species of tree frog inhabiting the Amazon rainforest. But it’s ineligible. Likewise, a claim that protects an old car “wherein said car is covered by a sales agreement, wherein said agreement is [insert non-obvious terms]” is ineligible not because the old car is “abstract” but because the “new” sales agreement is — beyond any doubt — an abstraction that you can not protect with a patent. And a claim such as the one I just described would protect that abstraction in the old car context. Therefore the claim is ineligible. That’s not a difficult analysis (it’s very easy, in fact) and it’s absolutely the correct result. Why do people so often pretend otherwise?

Lastly, kudos to the authors here for recognizing something fundamental: all the primary patent statutes, including 101, are overlapping with the others because at the end of the day the same policy considerations inform each of them. This is why it’s not unusual for the worst claims to fail all of the statutes simultaneously.

MM, information is not one of the four classes. It may also be abstract in a sense, but not in the sense the Supreme Court had in mind in cases like Le Roy v. Tatham. Those cases dealt in claims to results, claims claiming beyond any possible written description or enablement.

The problems are distinct.

information is not one of the four classes

You and I can agree on that. But there’s no reason to assume that everybody agrees. On the contrary, I’m certain that people in the comments here have argued that information can qualify as a “manufacture” (“it was made by man”). Heck, we have a regular commenter here who runs around squealing every other day that instructions are “machine components.”

[Information] may also be abstract in a sense

“May”? Of course it’s an abstraction. As we’ve discussed here ad nauseum, just because something has value or because it’s useful doesn’t mean it isn’t abstract.

But let’s assume that information is excluded because “not a category”. Why is it excluded? After all, we live in the Information Age! Why are we excluding the most valuable stuff from the patent system?

Some people like to pretend that there isn’t a good answer to this question.

“ I’m certain that people in the comments here have argued that information can qualify as a “manufacture” (“it was made by man”). ”

You do realize that THAT is not the argument, right?

Somehow (gosh, I a hope that no one is offended) copyright may inure to protect expression that copyright protects, but utility (as in that functionally related thing) somehow is deigned (by the self-appointed guardian of the patent fields of rye) to be off-limits from protection. Never mind the fact that software – as a computer ware – is merely a design choice to hardware and is thus easily seen as patent eligible.

Can you put away the strawman on “information” now?

software – as a computer ware

Round and round you go.

Clearly, you do not know (or are purposefully pretending that you do not know) what software is to a person having ordinary skill in the arts.

Dear anon,

I’m still wondering if you are the same as Anon from IPWD (Gene’s site). Anyway, your view contradicts the PTO position. In the Final Office Action regarding my application 14/027820, the Examiner specifically stated that “the combination of operations automates a mental process that could be performed by a “human analog.” For example, a human being can purchase a discounted gift card from a merchant.” If buying gift cards can be done by thought alone, any computer method can be seeing as merely imitating human brain. Further, the Examiner stated that “the steps disclose a sequence of operations that include obtaining information, transferring information, and receiving information.” Isn’t it what all software systems do? The Examiner finished the evaluation by pointing out that “the Examiner respectfully notes that the needed “improvement” in terms of patent eligibility is not one resulting from programming a generic processor to perform a different (or even improved) function, but rather a specific and actual improvement to the machine itself is needed.”

You may cite McRO, Amdocs, even Alice and Bilski, but the Examiner simply has several templates for rejection and just wants to play golf, so the arguments simply don’t matter. It is not possible to make a persuasive objection if, for example, the Examiner says that gift card processing (or gift cards in general) is not a technology, as all the references will be just ignored.

All patents in the USPTO database is nothing but information about implementing inventions. Alice simply gave the PTO an excuse to reject the max number of application in the min time.

Sincerely, -Alex

Some replies are still hung up, but are you confusing me wih that guy that uses a capital “A”…?

😉