by Dennis Crouch

In September 2018, the USPTO rewrote several Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). Revised SOP2 creates the Precedential Opinion Panel (POP) to be convened to rehear issues of “exceptional importance” as well as for re-designating prior opinions as precedential, when deemed appropriate. According to SOP2, the Precedential Opinion Panel will “typically” include the PTO Director, Commissioner for Patents, and the PTAB Chief Judge.

In what I believe is the first such precedential panel, the POP is set to review a prior PTAB decision in Proppant Express Investments, LLC (PropX) v. Oren Technologies, LLC (Oren), IPR2018-00914, with POP constituting the panel of Dir. Iancu, Com. Hirshfeld, and Chief Judge Boalick. The rehearing will focus on the practice of issue and party joinder under 35 U.S.C. § 315(c) — particularly focusing on the three questions:

- Under 35 U.S.C. § 315(c) may a petitioner be joined to a proceeding in which it is already a party?

- Does 35 U.S.C. § 315(c) permit joinder of new issues into an existing proceeding?

- Does the existence of a time bar under 35 U.S.C. § 315(b), or any other relevant facts, have any impact on the first two questions?

Amicus briefs (15 pages) are authorized, and should be submitted to trials@uspto.gov by December 28, 2018.

Section 315(c) indicates that, after institution of an IPR, the Director may, “in his or her discretion”, join “any person who properly files” an IPR petition that the Director “determines warrants … institution.” Section 315(b) bars institution of IPR proceedings for petitions filed more than one year after the petitioner (or privy) was served with an infringement complaint of the patent at issue.

In the case here, PropX filed a first IPR petition against Oren’s patent and then later filed a second petition against the same patent raising an additional issue along with a 315(c) joinder request (to join the second case with the first). One problem with the second petition was that it was filed after the 1-year deadline of 315(b). PropX argued that the 315(b) deadline does not apply to joinder cases under 315(c). A second problem is that 315(c) appears to be focused on joinder of parties — not the same party joining additional issues.

In its decision, the PTAB sided with the patentee and refused to allow the late-filed issue joinder petition — denying institution. It is that decision that the Director Iancu and his team will now review. Note here that the PropX decision was not one of first impression. Prior panels came out the other way. See, Target Corp. v. Destination Maternity Corp., Case IPR2014-00508 (Paper 28) (PTAB Feb. 12, 2015) (concluding that 35 U.S.C. § 315(c) permits a petitioner to be joined to a proceeding in which it is already a party); Nidec Motor Corp. v. Zhongshan Broad Ocean Motor Co., Case IPR 2015-00762 (Paper 16) (PTAB Oct. 5, 2015).

Although the 315(b)/315(c) decision has not been identically addressed by the, in dicta, Judges Dyk and Wallach wrote that it is “unlikely that Congress intended that petitioners could employ the joinder provision to circumvent the time bar by adding time-barred issues to an otherwise timely proceeding.” Nidec Motor Corp. v. Zhongshan Broad Ocean Motor Co. Ltd., 868 F.3d 1013, 1019 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (2-member concurring opinion)

= = =

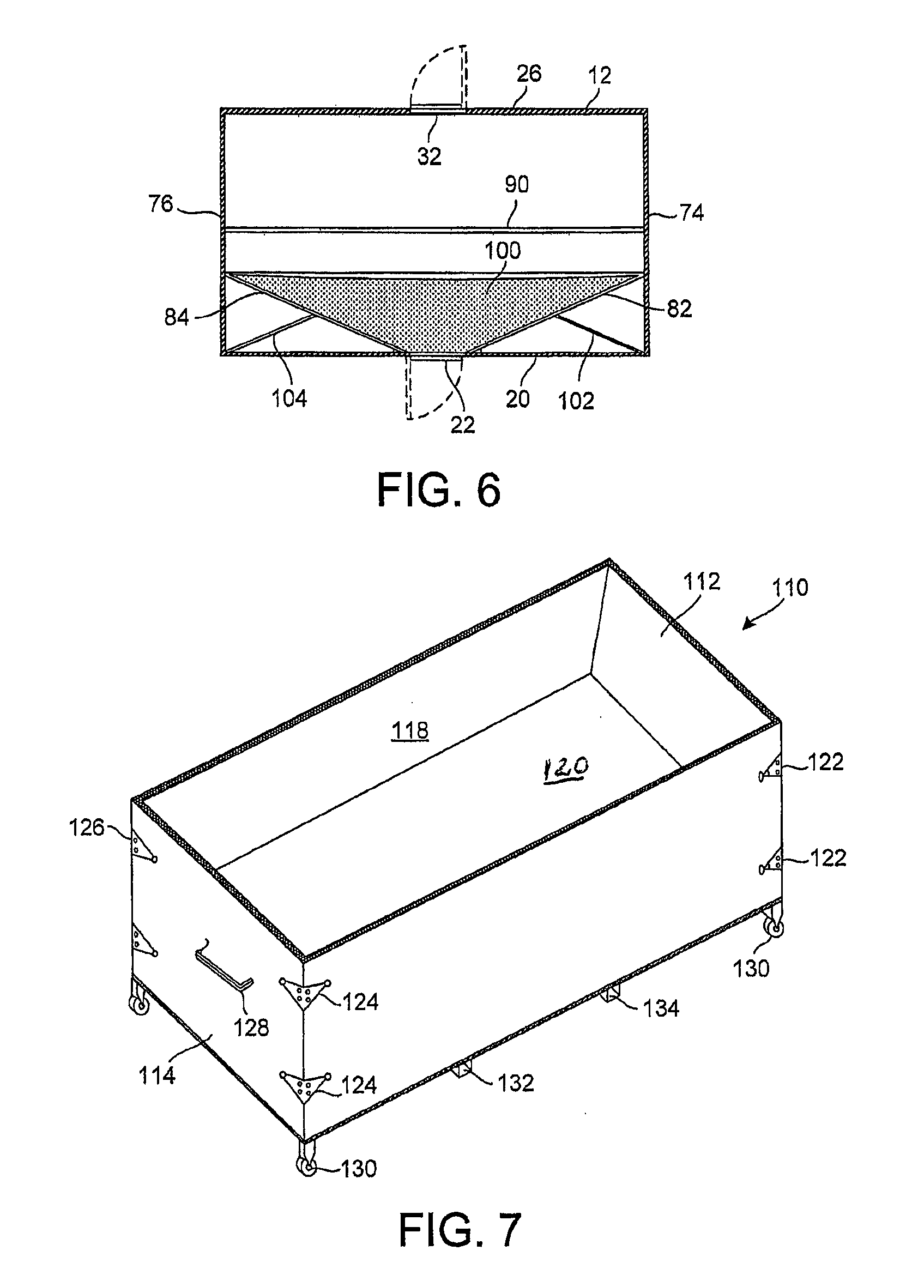

Patent at issue: 9,511,929, covering a container for storing and transporting “large volumes of proppant.”

Paul @8 and others:

My article responding to the Proppant order is now up at SSRN, link to ssrn.com

Paul asks two questions. Let’s look at them in reverse order.

Paul asks “a statutory expanded board with the Director, as here, can provide PTO interpretation for Chevron guidance.”

“Expanded panels” and “precedential opinions” are not specifically “statutory.” They’re just within the blanket authority of the Director to designate panels under § 6. An expanded panel, precedential opinion panel, or panel that decides to call itself “Emperor of the Universe and Protector of the Faith” has no more authority than any other. When the Director sits on a panel, he simply has one vote, same as any other APJ. The Director has no fairy dust to convert a PTAB panel to anything more than a PTAB panel. In re Alappat, 33 F.3d 1526, 1535, 31 USPQ2d 1545, 1550 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (“although the [Director] may sit on the Board, in that capacity he serves as any other member. … In other words, the [Director] has but one vote on any panel on which he sits, and he may not control the way any individual member of a Board panel votes on a particular matter.”), quoting Animal Legal Defense Fund v. Quigg, 932 F.2d 920, 928-29, 18 USPQ2d 1677, 1684 (Fed. Cir. 1991).

But you bring up a question of Chevron deference. Chevron is not a grant of additional rulemaking authority to agencies, nor a carve-out from the APA. Chevron is only a standard of review rule for agency actions that are otherwise valid exercises of agency authority.

To be sure, there are situations where a court has granted Chevron deference to an agency formal adjudication. But Proppant shares nothing in common with those cases. In cases where the Supreme Court granted Chevron deference to a rule-by-adjudication, two things were true:

(a) the adjudication tribunal also had rulemaking authority. For example, the NLRB, Interstate Commerce Commission, Federal Trade Commission, and Board of Immigration Appeals have both rulemaking authority and adjudication authority, integrated in a single agency component. Decisions of these tribunals can be eligible for Chevron deference. Not the PTAB. The Patent Act grants the PTAB no rulemaking authority.

(b) the tribunal acted as a “formal adjudication” tribunal under 5 U.S.C. § 554. Here. neither the parties nor the public have statutory notice. The PTAB’s choice to follow its established pattern of scofflawry, legal incompetence, and brazen defiance of law, on the simplest issue in the book, simple god damn notice, means that no rule emerging from Proppant can possibly mature into a rule eligible for Chevron deference.

Paul asks “when a party in a PTO proceeding raises a new issue that is not clear … that the PTAB cannot [and should not] stop the proceeding and wait until next year for z formal rulemaking process?”

The APA is immensely practical, and has been since 1948. The PTAB has the authority to do two things: adjudicate (under 35 U.S.C. § 318), and to interpret “active ambiguity” in language that has “some tangible meaning” (resolve ambiguous terms, resolve clashes, and the like) under 5 U.S.C. § 553(b)(A) , but not to gap fill. “Interpretative” rule authority does not extend even as far as to elaborate on empty or vague language like “fair and equitable” or “‘in the public interest.” Agencies are not Article III common law courts. Things we think of as perfectly reasonable for common law courts are well beyond the authority of agency tribunals.

The statute is clear: “The Director shall prescribe regulations to…” 35 U.S.C. § 316(a). Proppant‘s attempt to end run the APA and the Patent Act is completely outrageous. It’s mutiny. It’s a demonstration of the brazen disregard with which Commissioner Hershfeld and the PTAB hold the APA. (I won’t blame Director Iancu–he’s an Article III guy, and he has to rely on his senior staff. PTO senior executive service staff should know the APA inside out. If they do, they know it only the way a Mafia consigliere knows the law–in order to break it without getting caught.)

Re the commentary below about PTAB interpretations of the APA IPR statute and why they should be instead only be done by formal rule-making. Isn’t that ignoring the fact that when a party in a PTO proceeding raises a new issue that is not clear from the statute, existing rules, or prior Fed. Cir. decisions, that the PTAB cannot [and should not] stop the proceeding and wait until next year for z formal rulemaking process? Especially since that novel legal issue can be decided de novo by the Fed. Cir. by either party appealing. Also, a statutory expanded board with the Director, as here, can provide PTO interpretation for Chevron guidance.

No on both counts.

The PTAB has adjudicatory powers. All rulenaking power lies with the Director, and the statute says the Director may only make rules by “regulation.”

The PTAB may issue orders, but not make rules. Look at NLRB v Wyman-Gordon, 197 or so, for a perfect analogy.

Paul —

I wrote another article for Dennis on exactly this. Hopefully it gets posted in the next day or so! (He must be getting over all the champagne for the IAM 50 — congratulations Dennis).

Reply @9.

Whenever this patent gets to an IPR trial, do not these claims present some difficulties. E.g., how can the container [apparatus] claims distinguish prior art by claim elements of their intended use contents, as appears to be attempted here?

Since none of the comments here so far address any of the three listed questions to be decided by this expanded Board, I will take a shot at “2. Does 35 U.S.C. § 315(c) permit joinder of new issues into an existing proceeding?”

That might be in the interests of expediency, avoidance of duplicate proceedings, and validity [since the filing of the prior petition may inspire other potential or existing defendants to disclose better prior art], providing the “existing proceeding” has not already entered the trial phase and providing the joinder request is filed within the one year bar for the “existing proceeding” and providing the petitioner in the original proceeding files a declaration explaining why that issue was not previously raised in the ‘existing proceeding”?

Here is 35 USC 315(c) on joinder [and in 316 there is joinder deadline setting authority]:

c) Joinder- If the Director institutes an inter partes review, the Director, in his or her discretion, may join as a party to that inter partes review any person who properly files a petition under section 311 that the Director, after receiving a preliminary response under section 313 or the expiration of the time for filing such a response, determines warrants the institution of an inter partes review under section 314.

Paul,

How does that “play” with other aims of the AIA that sought to fragment the “joinder” situation (the “anti-tr011” provisions that direct more to non-joinder)…?

If that was a serious question, I have no idea what statute or rule you are referring to.

Part of the AIA drove suits purportedly filed by NPE’s to NOT have the suits joined, but forced the suits to be pursued on an individual basis. The portion of your “in the interests” comments at post 6 seem to fall away in that particular context. If so (in that context), then how does that “play with” the context you advance?

I recognize that these are two different things, but the driver behind them seems rather discordant.

“. . . and providing the joinder request is filed within the one year bar . . . .”

Most joinder requests were filed after the one-year bar, because the PTO interpreted 315(b) as successful joinder nullifying the bar. But the PTO also had a tortured reading of 315(c) such that a “party” could somehow “join” itself — i.e., allowing “issue” joinder. That reading came in the early days when they were not sure there would be enough business for the 200+ new PTAB hires.

Very different indeed. One was involuntary joining of numerous patent litigation defendants in the same suit even if they had different accused products, different locations, etc. The subject here is voluntary joinder of defendants, which IS still possible in patent litigation as well as to a limited extent in IPRs, the subject here.

Yes – different, but the “in the interests” remain the same, eh?

(even if “different products” and “different locations” there was still a basis for nexus)

Boundy: [L]aw is like religion, in that there’s no external reference for “truth,” and truth is truth because of who says it. In each of the two systems, there are limits on what can be said by what authority, but within that sphere, a statement by the relevant authority is the definition of a true statement.

Indeed. Which is why “the law” is in free-fall at the moment in this country. Guess who benefits most from that?

In each of the two systems, there are limits on what can be said by what authority

Oops — I missed this part, which is incorrect. There are no limits on what can be said. The limits are whatever people will put up with. I bring this up because I’m always surprised by what people will put up with. Like, there’s educated people out there (lawyers even!) who still can’t tell the difference between the two major political parties in this country and how they behave when they are in power, or why. And then there’s a whole other group of people who probably can tell but refuse to discuss it in any terms other than oblique terms (e.g., Dennis Crouch). Strange, sad times.

Your dissembling and misrepresentations are noted.

Thank you to Professor Crouch for performing a valuable public service by staying on top of related issues that are critical to any just legal system: precedent and explanation of judicial decisions (although this post only relates to the former).

Thanks Dennis. Follow-on” IPR petitions against the same patent are right up there with IPR claim amending as top IPR complaints [the latter has already been addressed]. So now there is a specific opportunity for those folks to file amicus briefs and obtain a precedential statutory Expanded Board opinion. [Of course the losing party could still appeal to the Fed. Cir.]

One issue not specifically among these three listed is denials of follow-on IPRs by Other parties, and the appropriate scope of that. Especially when incorrect identification of all “real parties in interest” is alleged by the patent owner along with a motion for expanded discovery on that issue.

Some people don’t learn from their mistakes.

Only a year ago, in Aqua Products, Inc. v. Matal, 872 F.3d 1290, 124 USPQ2d 1257 (Fed. Cir. 2017), the Federal Circuit set aside a PTO rule on an issue of substantive law, that goes beyond interpretation of existing statutory or regulatory language, promulgated by PTAB decision, without notice and comment. Though there were five separate opinions, the common ground on which a majority of the fragmented court could agree was that “[t]he Patent Office cannot effect an end-run around [the APA] by conducting rulemaking through adjudication.” Aqua Products, 872 F.3d at 1339, 124 USPQ2d at 1287 (Reyna, J. concurring, for the swing votes).

I don’t see a single relevant factual distinction on the rulemaking issue. Why is the PTAB so convinced that it’s above the law, and need not follow statutory rulemaking process, as mandated by the Administrative Procedure Act (5 U.S.C. § 553), Paperwork Reduction Act, and Executive Order 12,866?

Good analyses of the troubles that the PTAB is creating for itself are in:

The PTAB Is Not an Article III Court, Part 2: Aqua Products v. Matal as a Case Study in Administrative Law, ABA LANDSLIDE 10:5, pp. 44-51, 64 (May-Jun. 2018) (available at link to cambridgetechlaw.com)

and

David Boundy, The PTAB is Not an Article III Court, Part 3:Precedential and Informative Decisions, forthcoming in AIPLA Quarterly Journal, available at link to ssrn.com

Maybe this weekend I’ll write another article, and a brief.

Good grief.

+1 – I was just thinking the same thing as to executive agency self-designating its judiciary-type role with “precedential” effects.

Precedent… for whom?

Only as precedent for other IPR decisions by PTAB panels. That is all they have ever asserted their IPR precedential decisions are precedents for.

Only as precedent for other IPR decisions by PTAB panels. That is all they have ever asserted their IPR precedential decisions are precedents for.

Seems like a great idea, in any event.

The Ends do not justify the Means.

Your “sounds like” shows (as typical) an absence of critical thinking.

Acting outside rulemakng, the PTAB can issue housekeeping rules that bind the agency on prcedural rules vis-a-vis the public.

But the PTAB cannot bind any member of the public vis-a-vis the agency or any adversary.

Precedent shmecedent. The Administrative Procedure Act never mentions “precedential decision” as an alternative to the rulemaking procedures of section 553. This is just baloney thinking and nincompoop lawyering by PTO’s regulatory counsel.

Exactly.

And yet, it comes as no surprise that the two commentators wanting to gloss over this (or magnify the error) are the two most known for cheerleading the IPR mechanism and one of the most anti-patent posters in these boards.

As long as patent rights are being diminished, these two are like the proverbial Alfred E. Neumann’s “What me worry?”

Sorry to be dense — which “rule” are you referring to? Are you referring to the USPTO’s arrogation of authority in establishing the POP procedure?

Notpaidto_comment — Read Aqua and the Part 2 article.

David – I appreciate your efforts to hold the USPTO’s feet to the fire on the APA. Isn’t the problem at root that adjudication of property rights does not fit in the APA and administrative tribunals are contrary to American jurisprudence? No set of rules and regulations can result in due process for taking away a property right. They are pretending to be what only an Article III court can be. I hear PTAB APJ’s talking about developing the common law through precedential decisions and expanded panels – heresy! The executive branch does not develop the common law – not on this continent.

The due process gap in the Oil States decision is massive.

To adjudicate a vested property right, the rules would be:

1. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rules 1 to 86

2. Independent Judge with tenure appointed with Senate consent

3. Trial by jury on patents valued over $20

How about a notice and comment on that set of rules? PTAB is a house of cards. This is not a regulatory issue. It doesn’t fit. What they have been trying to do cannot be done under the APA. No matter how many rules are written, they cannot say with legal legitimacy that a property right never existed. In fact, most of the patents cancelled by the PTAB are in fact valid when tried in a real court. Even if they comply with the APA that just means they complied with the APA – they did not resolve the validity of the property right.

At bottom these administrative decisions must be considered merely advisory. APA cannot save it.

Josh Malone —

Some of this, unfortunately, is water under the bridge. The Supreme Court says it’s constitutional, so it is. (Like Catholocism: when the Pope speaks ex cathedra, that’s the definition of “truth” in that system. Same in American law. Truth is “truth” because of who says it. Depending on the issue, that can be Congress, the President, or the Supreme Court.)

I don’t see any reason that the PTAB couldn’t, theoretically, be an entirely sound adjudicative tribunal. (That’s not to say I like it, but it could be “sound” within the range of possibilities available under today’s statute.) PTAB’s pervasive neglect of the Administrative Procedure Act is explained in my Part 3 article.

Wow – the illustration you choose David is enlightening…

Like the Pope and ex cathedra…?

Thing is, unlike Canon Law, the US system does NOT place the Supreme Court above the Constitution (we really do have a checks and balances system and the “Supreme” of the “Supreme Court” is most definitely NOT like the Pope.

I didn’t say “above.” The Supreme Court can only interpret, no more than that. So the Supreme Court is subservient to the text. But the power to say what the Constitution means is a pretty vast power, when so much of the Constitution is written in aspirational terms.

Sorry you read more into it than I meant. I meant only what I wrote — that law is like religion, in that there’s no external reference for “truth,” and truth is truth because of who says it. In each of the two systems, there are limits on what can be said by what authority, but within that sphere, a statement by the relevant authority is the definition of a true statement.

Funny that, your “law is like a religion” was exactly what I was responding to.

Maybe you want to think about that analogy a little more – our Supreme Court is NOT like the Pope.

our Supreme Court is NOT like the Pope.

Until the day that it decides that the Framers intended it to be exactly like the Pope.

And why not?

Heck, it decided that voter suppression by r @ ci s t s in the South was no longer a problem so it’s not like they are bound to reality.

Our Justice Ginsburg would look ravishing in one of those post-hole digger Pope hats.

“And why not?”

Is that supposed to be a real question?

(A: because of the Constitution and separation of powers and government of limited powers — this is fundamental stuff)

There are many, many, many ways in which “our Supreme Court is NOT like the Pope.” My analogy relates to one and only one similarity.

Right – the notion of “Truth” in the legal sense – a sense for which the separation of powers, the limited powers of the government and the checks and balances ACROSS ALL THREE BRANCHES wrecks your Pope analogy.

Maybe you need to check again on that Pope analogy – the Supreme Court was never meant to be like that.

PTAB is cleaning up neglect by the PTO.

Remember: Boundy only worries about “illegal” activity at the PTO when it favors his rich friends.

Zillions of junk patents illegally granted? Whatevs.

Your whining about Boundy is fricking hilarious. You base “justice” on your wants alone, seeking to deny patent protection to the form of innovation most accessible to the NON-one-percenters at the same time of accusing a person known to champion a strong and fair patent system (Tafas, anyone?) of doing so only for “rich” friends…

The dichotomy is stultifying.

Josh,

“At bottom these administrative decisions must be considered merely advisory”

That is most definitely not what Congress did, and in our system, not even the Supreme Court may “re-legislate” and arrive at your “at bottom.”

What they can do is throw out (upon proper conditions being met) a law that attempts to improperly blur the distinctions between the branches. Once that is done, then Congress may want to “try again” (and get it right).

The “property rights” thing was put to bed, Josh. Sorry.

The real problem is that an agency is handing out “rights” illegally in many cases which limit my freedom. You and David Boundy don’t have a problem with that, particularly. And we can guess why.

“an agency is handing out “rights” illegally in many cases which limit my freedom.”

The same freedom to do whatever with the ineligible protons, neutrons and electrons that the Big Box can configure into any thing.

You mean that “freedom”…?

The Federal Circuit is hearing oral arguments next week in a VirNetX/Mangrove Partners case raising a similar issue—interesting timing

Comments are closed.