I previously wrote about the most cited Supreme Court patent cases since 1952. Today, I’ll write about the least-cited decision: Sanford v. Kepner, 344 U.S. 13 (1952).

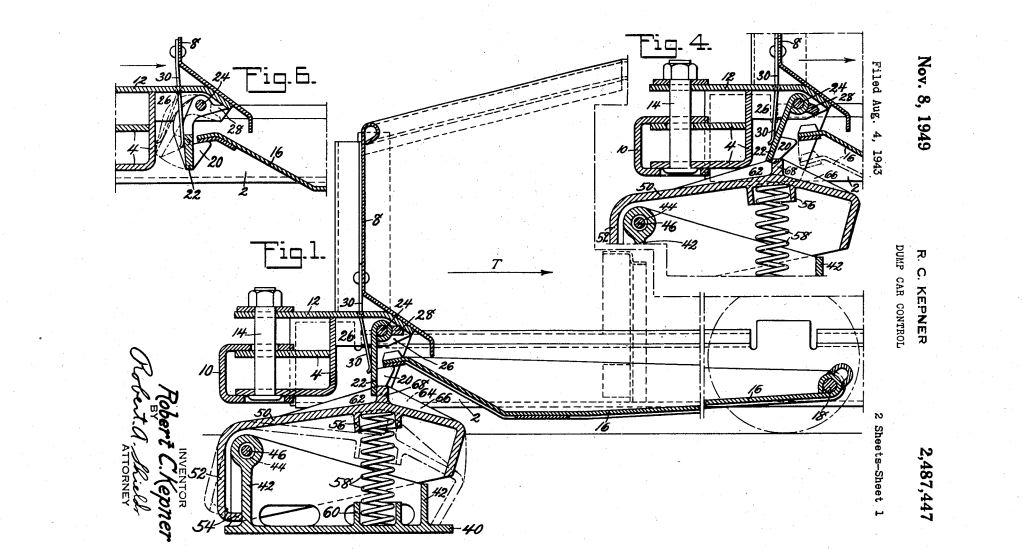

Kepner filed his patent application in 1943 and Sanford filed his in 1945 — both directed to drop-bottom rail cars used in mining.

The USPTO interference sided with the first-filer Kepner and so Sanford took the case to Federal Court. Sanford argued (1) that Sanford should have priority as the first-to-invent and thus get the patent; and (2) even if Kepner gets priority, Kepner’s patent should still be invalidated based upon the prior art. (“Void for lack of invention.”) The Pennsylvania district court sided with the first-filer Kepner on priority grounds, and refused to decide the question of patentability. Sanford v. Kepner, 99 F. Supp. 221, 222 (M.D. Pa. 1951). On appeal, Sanford argued that the district court should have decided the validity question also, but the appellate court affirmed. Sanford v. Kepner, 195 F.2d 387, 390 (3d Cir. 1952). In particular, the 3rd Circuit explained that once the priority issues are decided, the plaintiff would need some additional justification to maintain standing: “some manifest threat … or interference with the activities of the petitioner beyond the issuance of a patent to another is required to create a controversy justiciable under the Declaratory Judgment Act.” Id. The Supreme Court then took up the case and again affirmed, with Justice Black writing a short opinion for a unanimous court. Sanford v. Kepner, 344 U.S. 13 (1952).

The USPTO interference sided with the first-filer Kepner and so Sanford took the case to Federal Court. Sanford argued (1) that Sanford should have priority as the first-to-invent and thus get the patent; and (2) even if Kepner gets priority, Kepner’s patent should still be invalidated based upon the prior art. (“Void for lack of invention.”) The Pennsylvania district court sided with the first-filer Kepner on priority grounds, and refused to decide the question of patentability. Sanford v. Kepner, 99 F. Supp. 221, 222 (M.D. Pa. 1951). On appeal, Sanford argued that the district court should have decided the validity question also, but the appellate court affirmed. Sanford v. Kepner, 195 F.2d 387, 390 (3d Cir. 1952). In particular, the 3rd Circuit explained that once the priority issues are decided, the plaintiff would need some additional justification to maintain standing: “some manifest threat … or interference with the activities of the petitioner beyond the issuance of a patent to another is required to create a controversy justiciable under the Declaratory Judgment Act.” Id. The Supreme Court then took up the case and again affirmed, with Justice Black writing a short opinion for a unanimous court. Sanford v. Kepner, 344 U.S. 13 (1952).

In its decision, the court noted that the odd setup would likely result in a weak validity challenge:

There would be no attack on the patent comparable to that of an infringement action. Here. the very person who claimed an invention now asks to prove that Kepner’s similar device was no invention at all because of patents issued long before either party made claim for his discovery. There is no real issue of invention between the parties here and we see no reason to read into the statute a district court’s compulsory duty to adjudicate validity.

Id. Affirmed.

One reason this Sanford v. Kepner, 344 U.S. 13 (1952) situation was not likely to occur again [of losing an interference on invention priority without any PTO validity decision on subject claims]: Interferences at that time were tried and decided by a separate Board of Interferences which did not itself decide patentability issues. After the statutory merger of both PTO Boards [now many years ago] that ended and the logical practice became to decide contested claim validity issued first, in the interference motion period, before conducting any priority trial.

Interesting. I have never heard of this case before, and have—therefore—never read it. Based on your summary, however, it sounds like it sits a little uneasily with the reasoning of Cardinal Chem. Co. v. Morton Int’l., 508 U.S. 83 (1993). I wonder if the appellee in Cardinal Chem. cited Sanford in their brief?

Comments are closed.