by Dennis Crouch

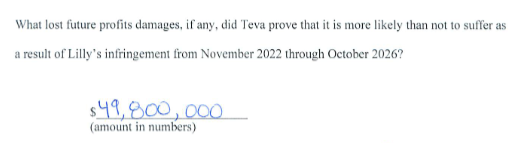

I had been following the case of Teva v. Lilly for a few years. Teva has traditionally been a generic manufacturer, but in this case sued Eli Lilly for infringing its patents covering methods of treating headache disorders like migraine using humanized antibodies that bind to and antagonize calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a protein associated with migraine pain. U.S. Patent Nos. 8,586,045, 9,884,907 and 9,884,908. The patents cover Teva's drug Ajovy, and allegedly cover Lilly's Emgality. Both drugs were approved by the FDA in September 2018. A Massachusetts jury sided with Teva and awarded $177 million in damages, including a controversial future-lost-profit award.

Although the jury sided with Teva, District Judge Allison Burroughs rejected the verdict and instead concluded that Teva's patent claims were invalid as a matter of law for lacking

Although the jury sided with Teva, District Judge Allison Burroughs rejected the verdict and instead concluded that Teva's patent claims were invalid as a matter of law for lacking

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.