by Dennis Crouch

Section 256 of the Patent Act is a remarkable statutory provision. It declares that a patent "shall not be invalidated" on the grounds of incorrect inventorship so long as the error "can be corrected." 35 U.S.C. § 256(a). Unlike its neighboring provisions for correcting other types of patent errors, Section 256 operates retroactively, reaching back to the patent's original filing date. And the statute imposes no express timing requirement: it does not say "if corrected within X days" or "if diligently pursued." The statute simply says "if it can be corrected." In Implicit, LLC v. Sonos, Inc., No. 2020-1173 (Fed. Cir. Mar. 9, 2026), however, the Federal Circuit held that the absence of a statutory deadline does not immunize a patentee from the consequences of delay. Forfeiture principles, the court ruled, can prevent a patent owner from relying on a Section 256 correction to mount a new argument in an inter partes review that it failed to raise during the original proceeding.

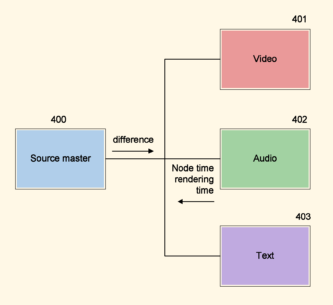

The case involved two patents owned by Implicit that originally named Edward Balassanian and Scott Bradley as co-inventors. Both were employees of BeComm Corporation, Implicit's predecessor. A third engineer, Guy Carpenter, had written the source code and authored the document that became the provisional application, but was not a named inventor.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.