All posts by Dennis Crouch

Parts vs. Whole: Federal Circuit Corrects District Court’s Component-Level Section 101 Analysis in Gene Therapy Case

SCOTUSGate: A New Portal to the Certiorari Pipeline

by Dennis Crouch

For many years, I relied on certpool.com to keep tabs on the Supreme Court’s certiorari docket. When that site went dark, I started building my own tracker in 2024, running it locally on my personal computer and checking it daily for new and interesting cases before the US Supreme Court. That project has now grown into SCOTUSGate.com, which I’m making publicly available for the first time. The site is very much in alpha, a work in progress, but it is functional and I’d welcome feedback from readers as it develops.

SCOTUSGate tracks petitions for certiorari and shadow-docket activity across the full Supreme Court docket. The database (named Cerberus, after the three-headed dog who guards the gates of the underworld) currently shows over 1,000 pending petitions, with structured data on conference scheduling, cert-stage briefing, CVSG invitations, and case dispositions. The site pulls docket information directly from the Court several times per day and I have incorporated both traditional text analysis tools as well as AI to extract questions presented from petition PDFs and assign topic tags for filtering and discovery.

The name works on a few levels. A gate as portal: the site is a point of entry into information about what the Court is considering. A gate as barrier: the certiorari process is itself a gate, with the Court granting review in only a small fraction of cases. And in the Watergate tradition of institutional-accountability naming: a site built on the conviction that the Court’s work should be visible and open to scrutiny, particularly at the cert and shadow-docket stages where transparency is most limited. (more…)

“Anonymous Work” and the AI Author Fight

An Inexact Art: Willis Electric and the Limits of Damages Gatekeeping

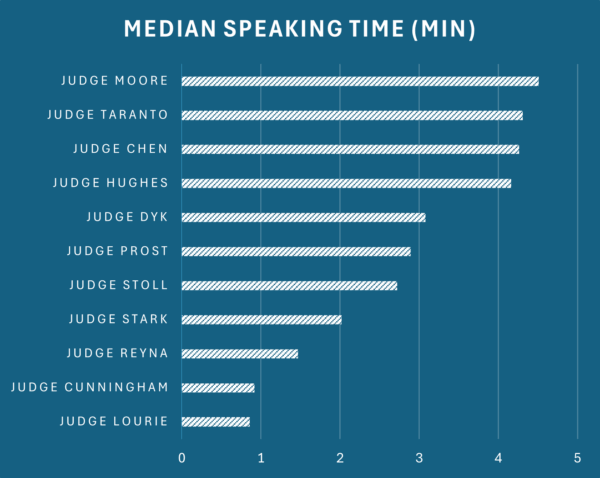

Hot Bench: Speaking Time and Opinion Writing at the Federal Circuit

Lynk Labs Resource Guide

The Supreme Court will shortly decide whether to grant cert in Lynk Labs. At the suggestion of a reader, I wanted to make these posts about the case available to non-subscribers seeking to research the issues.

- Dennis Crouch, Prior Art Document vs. Prior Art Process: How Lynk Labs Exposes a Fundamental Ambiguity in Patent Law, Patently-O (July 9, 2025), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2025/07/document-fundamental-ambiguity.html. Identifies a previously unnoticed conceptual tension in patent law between two competing frameworks—“prior art as document” versus “prior art as process.” I argue that this ambiguity explains why §311(b)’s seemingly straightforward language becomes so contentious when applied to §102(a)(2) springing prior art.

- Dennis Crouch, Lynk Labs: How the Least-Vetted Documents Destroy Issued Patents, Patently-O (Dec. 15, 2025), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2025/12/documents-destroy-patents.html. Argues the Federal Circuit’s decision creates perverse incentives by allowing abandoned, unexamined patent applications to be backdated as printed publications to invalidate issued patents. Surveys the substantial amicus landscape supporting cert, including briefs from former USPTO Director Kappos, former Chief Judge Michel, and IP scholars led by Professor Sichelman.

- Dennis Crouch, Thinking back on Milburn and Secret/Springing Prior Art, Patently-O (July 15, 2025), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2025/07/thinking-milburn-springing.html. Traces the historical foundation of the springing prior art doctrine from the Supreme Court’s 1926 Milburn decision through its modern expansion, providing doctrinal context for the Lynk Labs dispute.

- Tim Hsieh, Guest Post: The Supreme Court Should Clarify How to Apply Loper Bright in the Patent Law Case of Lynk Labs, Inc. v. Samsung Co. Ltd., Patently-O (Dec. 3, 2025), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2025/12/hsieh-lynk-loper.html. Professor Hsieh argues that the Federal Circuit’s decision effectively resurrects Chevron-style deference under a different label by tracking USPTO policy rationales rather than exercising independent judicial judgment, framing Lynk Labs as a critical test of Loper Bright’s reach.

- Dennis Crouch, Secret Springing Prior Art and Joint Research: Lessons from Merck v. Hopewell, Patently-O (Nov. 4, 2025), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2025/11/springing-research-hopewell.html. Examines the Federal Circuit’s Merck v. Hopewell decision clarifying when a collaborator’s patent qualifies as prior art “by another,” and how the AIA has changed this category of secret springing prior art through §102(b)(2) and §102(c).

- Dennis Crouch, Publications Before Publishing and the Federal Circuit’s Temporal Gymnastics, Patently-O (Jan. 14, 2025), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2025/01/publications-publishing-gymnastics.html. Analyzes the Federal Circuit’s decision holding that published patent applications are prior art as of their filing date in IPR proceedings, even when they were non-public at the time the challenged patent was filed.

- Dennis Crouch, Supreme Court Asked to Resolve ‘Secret Springing Prior Art’ Controversy in IPR Proceedings, Patently-O (Sept. 18, 2025), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2025/09/springing-controversy-proceedings.html. Covers the filing of Lynk Labs’ cert petition (No. 25-308) asking whether patent applications that became publicly accessible only after the challenged patent’s critical date qualify as “prior art … printed publications” under §311(b).

- Dennis Crouch, Should Abandoned Applications Be Presumed Enabling? Supreme Court Asks for Response, Patently-O (Dec. 23, 2025), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2025/12/abandoned-applications-presumed.html. Addresses the related cert petition in Agilent v. Synthego, asking whether abandoned patent applications filled with prophetic examples should be presumed enabling as anticipatory prior art—a question with direct implications for the evidentiary standards governing the documents at issue in Lynk Labs.

- Dennis Crouch, The ‘Narrow’ Question That Appears in Half of PTAB Obviousness Decisions, Patently-O (Feb. 2026), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2026/02/question-obviousness-decisions.html. Critiques the BIO briefs filed by Samsung and the U.S. government urging denial of cert, finding their arguments about the decision’s limited impact “shockingly disingenuous” given that the post-AIA statute contains an essentially identical provision to the pre-AIA scheme at issue.

- Dennis Crouch, Secret Springing Prior Art and Inter Partes Review, Patently-O (Oct. 4, 2024), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2024/10/secret-springing-partes.html. Previews the Federal Circuit appeal and coins the term “secret springing prior art” to describe references that were secretly on file at the USPTO when a patent was filed but only became publicly accessible upon later publication.

The Director Unbound: Federal Circuit Holds NHK-Fintiv Exempt from APA Rulemaking

Ingevity’s $85 Million Lesson: Antitrust Tying Still Has Teeth

Pre-Alice Patents Keep Falling: Three Section 101 Decisions from the Federal Circuit

First Possession and Intellectual Property: A Supplement for Property Law

by Dennis Crouch

For my property law course this semester, students only get two credits, which means they get roughly half a page on patent law. That is not much space considering that I’ve written 9,000 posts covering every corner of our 235 year old system. The reading comes immediately after reading on Popov v. Hayashi and Pierson v. Post.

A core insight here is that Pierson v. Post, 3 Cai. R. 175 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1805), and the America Invents Act of 2011 are doing the same work. Both define a formal act that counts as “possession” and award priority to whoever performs it first. In Pierson, the act is killing or capturing the fox. In patent law, the act is filing the application. The shift from the old first-to-invent system to first-inventor-to-file is a rehash of the majority-dissent split in Pierson. The old regime, which rewarded the first person to conceive of an invention (so long as she proved diligence in reducing it to practice), resembled Justice Livingston’s dissent, which would have awarded the fox to the pursuer in hot chase. The new regime, like the Pierson majority, demands a clear, unambiguous act of capture. Note that this insight comes from Dotan Oliar & James Y. Stern, Right on Time: First Possession in Property and Intellectual Property, 99 B.U. L. Rev. 395 (2019), I just wrote it in a way that 1Ls can read and easily quickly. (more…)

Privity Without Duty: When Patent Inventors Are Bound but Not Represented

An Old Trick in the Patent Book: Targeted Drafting from 1876 to 2026

Patent Suit Over NASA’s Mars Helicopter Blocked by Government Contractor Immunity

The ‘Narrow’ Question That Appears in Half of PTAB Obviousness Decisions

by Dennis Crouch

Samsung and the U.S. government have filed briefs urging the Supreme Court to deny certiorari in Lynk Labs, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., No. 25-308. At issue is whether a patent application filed before a challenged patent’s priority date, but not published until afterwards, can serve as prior art in inter partes review. The Federal Circuit held that it can, applying the filing-date rule of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(e)(1). As I write below, I was not overly impressed with they briefing.

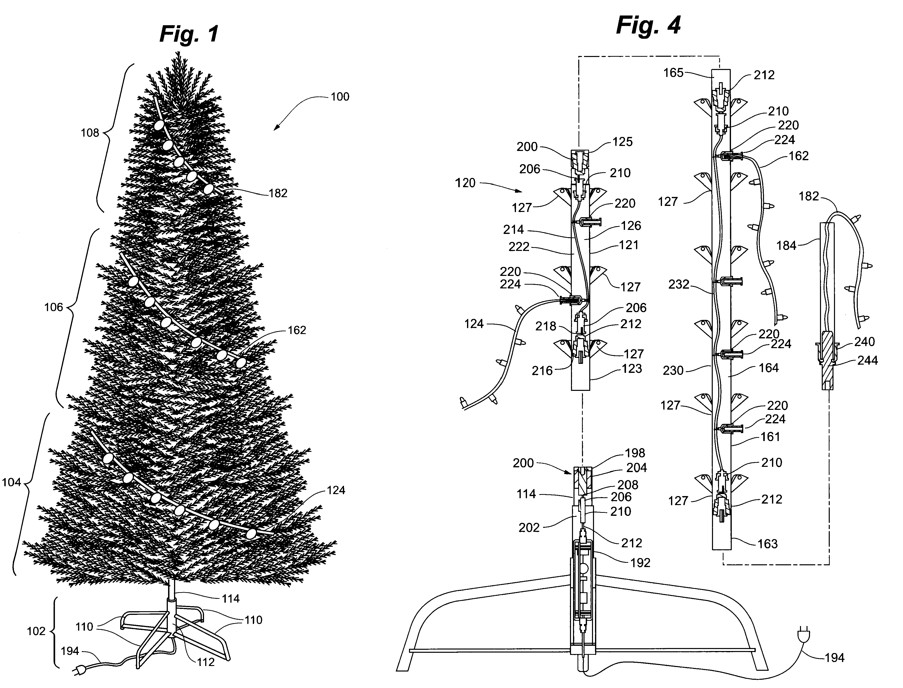

The case centers on the “Martin” reference, a patent application covering LED technology that was filed on April 16, 2003 and published on October 21, 2004. Martin was later abandoned and never became a patent. Lynk Labs’ ‘400 patent claims a priority date of February 25, 2004, placing it squarely in the gap between Martin’s filing and publication dates. Samsung successfully used Martin to challenge claims of the ‘400 patent as obvious in IPR.

As part of its streamlining effort, Congress limited what prior art can be used in inter partes review proceedings – only “prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.” 35 U.S.C. § 311(b). Although Martin was not publicly accessible when Lynk Labs filed its application, Martin was later published and also qualifies as prior art under pre-AIA 102(e)(1) (or its parallel post-AIA statute 102(a)(2)). In reading the statute, the court concluded that Martin can be used in an IPR because it satisfies each of the two requirements (prior art + printed publication) even though its prior art date is well before its publication date. Lynk’s cert petition frames this as a question about whether “printed publications” in § 311(b) carry the traditional public-accessibility timing requirement, or whether a published patent application can be backdated as prior art to its filing date in IPR.

I have previously written about this case at several stages. Dennis Crouch, Secret Springing Prior Art and Inter Partes Review, Patently-O (Oct. 2024); Dennis Crouch, Publications Before Publishing and the Federal Circuit’s Temporal Analysis, Patently-O (Jan. 2025); Dennis Crouch, Prior Art Document vs. Prior Art Process, Patently-O (July 2025); Dennis Crouch, Supreme Court Asked to Resolve “Secret Springing Prior Art” in Inter Partes Review Proceedings, Patently-O (Sept. 2025); Dennis Crouch, Lynk Labs: How the Least-Vetted Documents Destroy Issued Patents, Patently-O (December 2025).

Before getting into the merits of the responses, I first want to note how both briefs appear shockingly disingenuous in their discussion of the limited impact of the decision. (more…)