by Dennis Crouch

The Supreme Court has called for a response in Agilent Technologies, Inc. v. Synthego Corp., No. 25-570, a petition that challenges foundational assumptions about the use of prior art references. The response is due in January 2026. The basic question in the case is whether printed publications asserted as anticipatory prior art should be presumed enabling, and whether the Federal Circuit's holding in Rasmusson v. SmithKline Beecham Corp., 413 F.3d 1318 (Fed. Cir. 2005), that "proof of efficacy is not required" for a reference to anticipate, should be vacated or narrowed.

In this case, the allegedly anticipatory reference is an abandoned patent application filled with prophetic examples describing modifications that, according to Agilent, nobody has ever shown to work. The petition asks the Court to reconsider whether modern patent law has drifted too far from the principle articulated in Seymour v. Osborne, 78 U.S. (11 Wall.) 516 (1870), that a prior art reference must actually "communicate" the invention to the public in a meaningful sense to defeat a patent.

The Supreme Court's call for response (CFR) carries some procedural significance. The Court receives thousands of certiorari petitions each year and grants fewer than 80. Most petitions are denied without any response from the opposing party. When the Court requests a response, it signals that at least one Justice believes the questions warrant fuller consideration. This does not mean certiorari is likely; most CFR cases still result in denial. But it elevates the petition above the thousands that receive no engagement whatsoever. For a patent case raising questions about anticipation doctrine, this level of interest is worth noting. The enablement requirement for anticipatory prior art is not a question the Court has addressed directly in the modern era, and the petition frames the issue as one of growing practical importance as the nature of "printed publications" continues to shift.

The Enablement Presumption for Prior Art

When a patent challenger argues that a prior art reference anticipates a patent claim, courts apply a presumption that the reference is enabling. This means the challenger need not affirmatively prove the reference teaches a person of ordinary skill how to make and use the disclosed invention. Instead, the patentee bears the burden of proving the reference is not enabling. The rationale traces to an assumption that published technical documents generally reflect real knowledge. But this presumption can be rebutted by showing the reference contains inoperable embodiments or would require undue experimentation to practice.

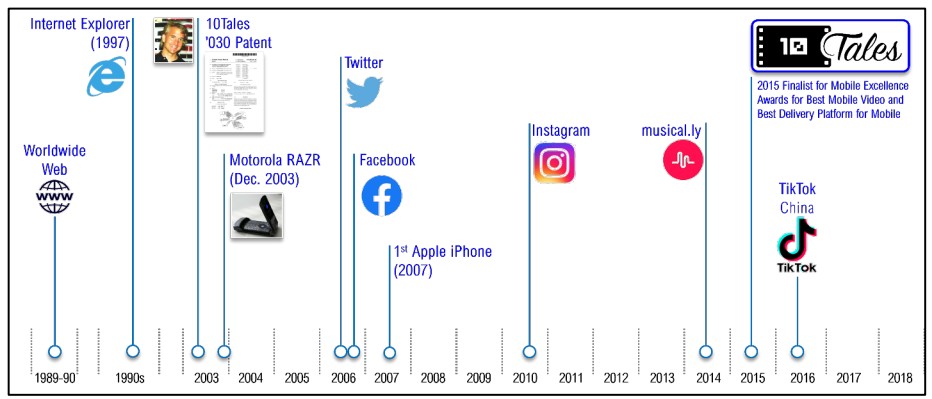

The underlying dispute involves Agilent's patents on modified guide RNAs used in CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Synthego challenged the patents before the PTAB, asserting anticipation based on a Pioneer Hybrid patent application. That application disclosed various guide polynucleotide modifications, including sequences presented in what the parties call "Table 8." The catch is that Pioneer Hybrid was abandoned, its examples were entirely prophetic rather than actually performed, and Agilent contends the vast majority of what it disclosed simply does not work. The Federal Circuit heard oral argument in the appeal from the PTAB's anticipation finding, and that case remains pending. But the Supreme Court petition challenges the doctrinal framework itself, regardless of how the Federal Circuit resolves the specific factual disputes.

The oral argument before the Federal Circuit, featuring Professor Mark Lemley for the patentee Agilent and Edward Reines for Synthego, illuminates the doctrinal stakes. Lemley framed two distinct but related arguments. First, that Pioneer Hybrid never actually disclosed functionality sufficient to put a person of ordinary skill in the art in possession of working guide RNAs. Second, even if some disclosure existed, the reference failed to enable because it "threw everything at the wall" without teaching which of the "quadrillion quadrillion possibilities" would actually function. Judge Prost pressed Lemley on whether these were anything more than substantial evidence arguments, asking whether the Board's detailed factual findings should receive deference. Lemley responded that the legal question was whether a reference that says "try anything" can satisfy enablement when a person of skill would have to conduct extensive trial-and-error experimentation to identify operable embodiments.

In my mind, the "throw everything at the wall" problem should receive a special spotlight as AI-generated technical content proliferates. Large language models have been producing vast quantities of plausible-sounding scientific disclosures. These are synthetic publications that read as authoritative but are untethered from actual experimentation -- and often from reality itself. Some of these AI-generated predictions will, by combinatorial luck, accurately describe functional embodiments. Yet nothing in their presentation distinguishes the prophetic hits from the prophetic misses; all carry the same veneer of technical respectability. Current anticipation doctrine, which presumes enabling disclosure and places the burden on patentees to prove otherwise, seems ill-equipped for a landscape where machine-generated prior art can flood the technical literature with untested possibilities. Requiring meaningful proof that a reference actually enables what it purports to disclose is one doctrinal lever for ensuring that anticipation remains grounded in genuine contributions to public knowledge rather than algorithmic speculation.