by Dennis Crouch

Economic historian Joel Mokyr recently received the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics (shared with Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt) for reshaping our understanding of why historic sustained technological progress and economic growth emerged in Europe in the 1700s. For patent law scholars and practitioners, Mokyr's work offers critical historical perspective on a question that echoes through modern IP policy debates: what institutional arrangements best promote innovation? His historic answer from the Industrial Revolution push against any patent-centric narrative, but still argue that knowledge dissemination is the key factor.

Mokyr's central insight is that the explosion of sustained economic growth beginning around 1750 resulted from an unprecedented accumulation and circulation of what he terms "useful knowledge." Joel Mokyr, Intellectual Property Rights, the Industrial Revolution, and the Beginnings of Modern Economic Growth, 99 Am. Econ. Rev. 349 (2009). This useful knowledge encompasses both propositional knowledge (understanding laws of nature and scientific principles) and prescriptive knowledge (understanding how to do things through practical techniques and skills). What made the Industrial Revolution revolutionary was not simply the existence of clever inventions, but rather the creation of positive feedback loops between scientific understanding and practical application, amplified by new institutions and cultural norms that encouraged the wide dissemination of both types of knowledge. The Enlightenment subsequently fostered what Mokyr calls an "Industrial Enlightenment" where artisans began engaging with natural philosophy and knowledge became viewed as a public good meant to improve human welfare rather than a proprietary secret to be guarded.

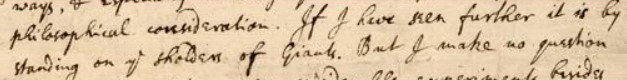

At this time, encyclopedias, technical journals, public lectures, and open demonstrations allowed practical knowledge to spread rapidly. The Royal Society of Arts promoted useful inventions through prizes and encouraged inventors to publish their methods rather than seek patents. Scientific academies in France and elsewhere operated similarly, offering pensions and honors to inventors who contributed to public knowledge. What emerges from Mokyr's account is a picture of innovation as fundamentally a social and cumulative process, with inventors standing on the shoulders of giants, as captured by Newton's famous phrase.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.