by Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit is set to decide an important issue regarding the scope of prior art that can be considered during inter partes review (IPR) proceedings in the pending appeal of Lynk Labs, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. At issue is whether section 102(a)(2) prior art qualifies for use in an IPR proceeding because those applications were not yet publicly accessible until after the priority date of the challenged patent. This case has very significant implications because 102(a)(2) prior art is extensively used – especially in crowded and rapidly moving areas of technology. The question, is whether this type of 102(a)(2) prior art qualifies as a “patent or printed-publication” under the IPR limits of section 311(b). Note that the same issue is raised in another pending CAFC case VLSI Tech. LLC v. Patent Quality Assurance LLC, No. 23-2298 (Fed. Cir.).

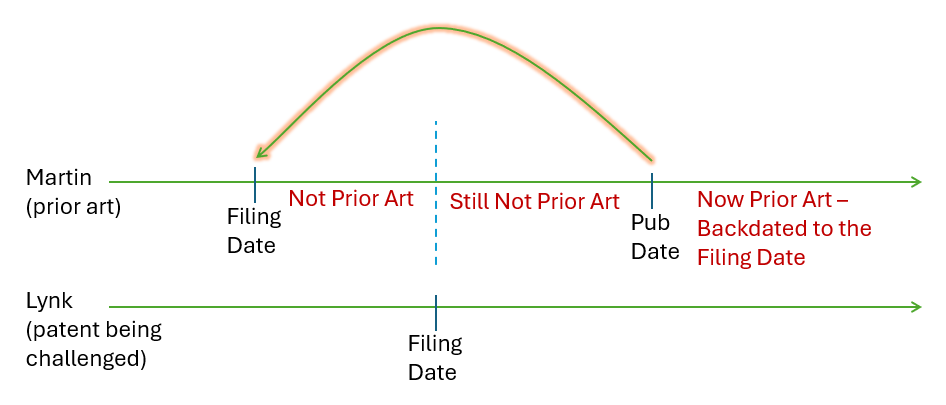

The dispute stems from an IPR petition filed by Samsung challenging claims of Lynk Labs’ U.S. Patent No. 10,687,400 (“the ‘400 patent”) related to LED lighting systems. Samsung’s petition relied upon a prior-filed patent application (“Martin”) as a key prior art reference. (Application No. 10/417,735 subsequently published as U.S. Patent App. Pub. No. 2004/0206970). This prior application is not prior art under 102(a)(1) – because it was not patented or published until after Lynk’s effective filing date. However, the prior application is prior art under the “secret springing prior art” provision of 102(a)(2), since it was on file prior to Lynk and then subsequently published. I refer to this as “secret springing prior art” because Martin was only secretly on file at the time Lynk filed its application – later, once Martin published it suddenly became prior art –back dated to the application filing date.

The PTAB instituted review and ultimately found the challenged claims unpatentable based in part on the Martin reference.

Briefs:

- Lynk – Opening Brief

- Lynk – Samsung Appellee Brief

- Lynk – USPTO Intervenor Brief

- Lynk – PIPLA Amicus

- Lynk – VLSI Amicus

- Lynk – HTIA Amicus

- Lynk – Intel Amicus

On appeal, Lynk argues that Martin does not qualify as a “printed publication” and therefore cannot serve as the basis a ground raised in an inter partes review petition or proceeding. My reading of the statutes leaves substantial ambiguity. However this is a close question: Lynk’s interpretation would substantially undermine the power of IPR proceedings and I don’t believe Congress was intending to avoid 102(a)(2) prior art when it wrote this portion of the statute.

An important point for the appeal — the PTO’s interpretation of the statute should be given no deference. On this point, the USPTO’s briefing points to long-standing USPTO practice of applying § 102(e)(1) to published applications in reexamination proceedings, which Congress did not expressly disturb when enacting the IPR statute. This idea, that Congress intended to reenact USPTO practice may have merit.

Let’s look at the two key statutes. First, the IPR statute 35 U.S.C. 311(b) limits the scope of inter partes review to certain types of arguments – known as “grounds.” In particular, the petitioner can only raise a ground that “could be raised under section 102 [novelty/bar] or 103 [obviousness]” and “only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.” Lynk contends that § 311(b)’s limitation of IPRs to “prior art consisting of patents or printed publications” requires that a reference be publicly accessible as of the critical date to qualify as a printed publication.

The second statute that is closely related here is the aforementioned section 102(a), which has been seen as defining the various forms of prior art available to judge patentability. 102(a)(1) generally references an invention being patented or described in a printed publication. But 102(a)(1) does not apply here because the prior art Martin was not published until after Lynk’s filing date. The next provision 102(a)(2) creates prior art in a situation where an application (i) is either patented or published and (ii) was filed before the application being challenged. (roughly).

Lynk’s argument in favor of excluding 102(a)(2) prior art from IPRs is rooted in both statutory interpretation and the historical understanding of “printed publications” in patent law, which has consistently required public accessibility for a reference to qualify as a printed publication. This interpretation, Lynk argues, is consistent with the historical treatment of unpublished patent applications, which were not considered printed publications. See Brown v. Guild, 90 U.S. 181 (1874) (distinguishing between “mere applications for patent” and “printed publications”).

The confusing element here is that 102(a)(2) does directly reference issued patents and applications that are published (or ‘deemed published’) — this makes it seem like the publication is the prior art. But I believe the word “published” in the statute is a bit of a red-herring that leads us astray. Although not the facts of this case, I think it helpful to consider a situation where the 102(a)(2) prior art is a prior application that was never “published” but is now “patented.” In that scenario, it would not sit well with me to conclude the application qualifies under the 311(b) “patented” prong as of its application filing date because it was not actually patented at that time. The patent did not exist and was not available to the public until its issue date. This interpretation aligns with the traditional understanding of “patented” in patent law, which has historically referred to the date a patent issues and becomes publicly available, not its earlier application filing date.

This hypothetical analysis of the “patented” prong of 311(b) helps me also understand the parallel “printed publication” prong and supports a consistent interpretation of both terms. Just as a patent should only be considered “patented” for 311(b) purposes as of its issue date, a printed publication should only be considered as such from its actual publication date. This interpretation hews closely to the historical understanding of these terms and aligns with the public notice function of the patent system. It avoids the problematic concept of “secret springing prior art” that retroactively becomes available for IPR challenges.

An amicus brief filed by the High Tech Inventors Alliance (HTIA) and Computer & Communications Industry Association (CCIA) emphasizes the practical importance of allowing published applications to serve as § 102(e)(1) prior art in IPRs. They argue this interpretation is necessary to fulfill Congress’s intent of providing an efficient alternative to district court litigation for reviewing patent validity. The amici contend that excluding published applications that were not publicly accessible as of the critical date would “curtail considerably the utility of prior art patent applications in IPRs, contrary to the AIA’s purpose of weeding out dubious patents.”

An amicus by the Public Interest Patent Law Institute (PIPLI) also supporting Samsung and arguing for broader prior art scope argues that published patent applications serve an important public interest function by protecting the public domain and benefiting both technology creators and users. PIPLI cites empirical research showing that IPRs leading to the cancellation of drug patents have resulted in significant price reductions for affected drugs. See Charles Duan, On the Appeal of Drug Patent Challenges, 2 AM. U. L. REV. 1177 (2023). The brief argues that Congress intended IPRs to improve patent quality, and excluding these prior-filed applications as prior art would be contrary to that intent.

Intel’s amicus also falls in line with the prior two – also arguing that published patent applications clearly qualify as “printed publications” under § 311(b) and are available as prior art in IPRs as of their filing dates. Intel contends that the plain text of § 311(b) covers published applications, which are printed and published documents. The brief cites numerous cases where courts and the Patent Office have consistently treated § 102(e)(1) art as proper grounds in IPRs and reexaminations for decades.

VLSI Technology LLC, on the other hand, argues that patent applications published after a challenged patent’s critical date do not qualify as “printed publications” under 35 U.S.C. § 311(b) and thus cannot be used in IPRs. VLSI contends that the statute’s text and history show Congress intended to exclude “applications for patent” as a separate category from “printed publications” in IPRs. VLSI reached a bit further back into history – to the 19th century – to explain that applications were not considered “printed publications” historically, and that Congress did not change this when creating IPRs.

The case is set for oral arguments on October 10, 2024 before a yet-unannounced panel of Federal Circuit judges.

Stephen Schreiner of Carmichael IP is set to argue for appellant Lynk Labs, Inc. and was joined on the brief by James Carmichael, Stephen McBride, and Minghui Yang.

Naveen Modi of Paul Hastings LLP will argue for appellee Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. and was joined on the brief by Joseph Palys, Igor Timofeyev, David Valente, and Daniel Zeilberger.

Michael Forman will represent the USPTO, and is splitting time with Modi.

VLSI’s attorney Jeffrey Lamken of MoloLamken LLP requested an opportunity to also argue, but was denied. VLSI’s brief was filed by Lamken along with Jordan Rice and Lucas Walker. Joseph Matal is representing High Tech Inventors Alliance and Computer & Communications Industry Association. William F. Lee of WilmerHale is representing Intel and joined on the brief by Benjamin Fernandez, Lauren Fletcher, Steven Horn, and Madeleine Laupheimer. Finally, Alexandra Moss of PIPLA filed the PIPLA amicus brief.

= = =

You know, I was about to say what a silly argument Lynk is making, but now I’m not so sure. I spend a lot of time in my patent classes teaching about printed publications (which has a definite meaning under (a)(1)) and patented (which also has a definite meaning under (a)(1)) and how those are different than described in a published patent or patent application.

So, to me, reliance on the patent being printed is not helpful at all. The real crux of the question is whether 311(b)’s “patents” was intended to be limited to “patented” under (a)(1) or to apply more generally to any kind of patent application or patent description under (a)(2). I don’t know the answer, but I also don’t think it’s an easy one without more.

AIA 102(a)(2) is not new, it is to the same effect as old prior 102(e). A common basis for claim rejections in untold thousands of applications and numerous patents including in reexaminations and interferences. The AIA 102 even further expanded its “springing prior art” impact by extending it back to Foriegn application priority dates claims in U.S. applications that get published and patented later than the subject patent or application, in the same statute that created the IPR.

As the Samsung brief suggests, the Sup. Ct rationale for prior 102(e) in Hazeltine Res., Inc. v. Brenner, 382 U.S. 252, 254-55 (1965) equally applies to IPRs under the AIA. It “would create an area where patents are awarded for unpatentable advances in the art.” Hazeltine, 382 U.S. at 256.”

Not a comment on the case itself, but I found the request of VLSI to get time at this oral argument pretty brazen and unprecedented, to say the least.

While I understand your view that VLSI’s request for oral argument time was unusual, I wouldn’t characterize it as brazen or entirely unprecedented. VLSI has a legitimate interest in the outcome of this case, as it raises the same legal issue central to VLSI’s own pending appeal before the Federal Circuit. Given the potential impact on VLSI’s patent rights and the fact that this case will likely be decided first, VLSI’s desire to be heard is understandable. In addition, the motion was a joint motion with appellant Lynk Labs — offering to give VLSI 5 minutes of time.

An important element here: I think the 311(b) is the most interesting part of this appeal, Lynk has actually raised a number of other issues – arguing that they should keep their patent even if Martin is useable prior art.

That said, the Federal Circuit denying VLSI’s request is not surprising. The court generally limits oral arguments to the named parties and formal intervenors, with exceptions being rare.

The PTO brief and the Intel brief got it right. The statute establishes an evidentiary standard.

Yes, 311(b) “Scope- A petitioner in an inter partes review may request to cancel as unpatentable 1 or more claims of a patent only on a ground that could be raised under section 102 or 103 and only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.” This is a ground raised under 102 and thus 102’s definition of what is a prior art patent or printed publication applies.