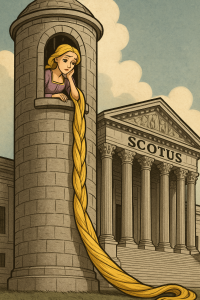

Rebecca Curtin, an IP-focused Suffolk law professor and a parent who purchases princess dolls, is setting up to file her petition for writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court on her pending trademark case. In Curtin v. United Trademark Holdings, Inc., No. 23-2140 (Fed. Cir. May 22, 2025), the Federal Circuit affirmed the TTAB dismissal of Curtin’s opposition to United Trademark Holdings’ application to register “RAPUNZEL” for dolls and toy figures under International Class 28. Curtin had challenged the mark as generic, merely descriptive, and failing to function as a trademark – arguing that registration refusal is necessary to protect the public’s right to use common language to describe categories of goods. The Federal Circuit’s ruling, however, concluded that consumers like Curtin lack statutory standing to bring such challenges under 15 U.S.C. § 1063, effectively limiting opposition proceedings to commercial actors with competitive interests in the marketplace.

Any person who believes that he would be damaged by the registration of a mark upon the principal register . . . may, upon payment of the prescribed fee, file an opposition . . .

The statute – quoted above – appears quite broad, but the Federal Circuit has tightly limited its application. Curtain’s brief is now due October 3, 2025.

- 20250801181357487_Cert Extension Application

- Prior Patently-O Post: Rapunzel, Rapunzel, Let Down Your Generic Hair (and Let Us In)!

The case represents a significant departure from earlier Federal Circuit precedent and raises fundamental questions about the scope of public participation in the trademark registration process. Under the Board’s prior, following Ritchie v. Simpson, 170 F.3d 1092 (Fed. Cir. 1999), any person who could show “a real interest in the proceeding” and “a reasonable basis” for believing they would be damaged by a mark’s registration could file an opposition. But the Federal Circuit’s new approach, drawing from the Supreme Court’s decision in Lexmark International, Inc. v. Static Control Components, Inc., 572 U.S. 118 (2014), now requires that opposers fall within the “zone of interests” protected by the Lanham Act and demonstrate proximate causation between the mark’s registration and their alleged harm. The court concluded that Curtin’s interests as a consumer purchasing fairy-tale themed dolls fell outside this protected zone, and that any harm she might suffer from RAPUNZEL’s registration was too attenuated because it flowed only derivatively through potential effects on commercial competitors.

Lexmark’s Framework and the Federal Circuit’s Extension: In Lexmark, the Supreme Court addressed false advertising claims under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a), holding that plaintiffs must demonstrate both that their interests fall within the “zone of interests” protected by the statute and that their injuries were proximately caused by the defendant’s violations. The statute does not affirmatively state a limit on statutory standing, but the Court found implicit limits within the Lanham Act’s statement of purposes in 15 U.S.C. § 1127. In that case, the court saw an important goal of the provision was “to protect persons engaged in such commerce against unfair competition.” Based upon that goal, the Court concluded that § 1125(a) protects commercial interests in reputation and sales, not broader consumer interests. The Lexmark Court emphasized:

A consumer who is hoodwinked into purchasing a disappointing product may well have an injury-in-fact cognizable under Article III, but he cannot invoke the protection of the Lanham Act.

While acknowledging that consumer protection is “a primary purpose of trademark law,” the Court distinguished between the ultimate beneficiaries of trademark protection and those Congress authorized to enforce it. This is the parallel approach taken in patent law’s eligibility doctrine – although concerns about preemption reign supreme, preemption is not actually considered in the analysis.

The Supreme Court in Lexmark acknowledged that § 1125(a) uses very broad language identifying who can sue – “any person who believes that he or she is likely to be damaged” – but the Court refused to read it literally. The court wrote:

Read literally, that broad language might suggest that an action is available to anyone who can satisfy the minimum requirements of Article III. No party makes that argument, however, and the “unlikelihood that Congress meant to allow all factually injured plaintiffs to recover persuades us that [§1125(a)] should not get such an expansive reading.”

Quoting a RICO case, Holmes v. Securities Investor Protection Corporation, 503 U. S. 258 (1992).

The Federal Circuit has since expanded Lexmark to apply in the in the USPTO/TTAB context. First in Corcamore, LLC v. SFM, LLC, 978 F.3d 1298 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (cancellation proceedings under § 1064) and now in Curtain (opposition proceedings under § 1063). In both cases, the statutory language permits challenges filed by “any person who believes that he would be damaged” by the mark. But, the appellate court concluded that the “any person” language should receive additional limitation based upon the same reasoning in Lexmark.

This represents a deliberate judicial choice to align TTAB administrative proceedings with federal court standards, rather than maintaining the historically more permissive approach that recognized the TTAB’s unique registry-cleaning function. The result then is that consumers generally do NOT have standing to take action under any major provision of the Lanham Act.

The Federal Circuit particularly rejected Curtin’s argument that opposition proceedings represent administrative participation rather than traditional causes of action, emphasizing the “linguistic and functional similarities” between §§ 1063 and 1064. Judge Hughes’s opinion stressed that because Curtin’s specific grounds for opposition – genericness, descriptiveness, and failure to function – are “rooted in commercial interests” designed to prevent competitors from monopolizing descriptive language, only commercial actors should have standing to raise these challenges.

Curtin’s Likely Arguments on Appeal

Curtin’s petition for certiorari will likely focus on the fundamental distinction between joining an ongoing administrative process and initiating a private enforcement action in federal court. Her strongest argument may be that Lexmark‘s framework, designed for district court litigation, should not automatically apply to administrative proceedings where Congress has explicitly invited broad public participation. This interpretation aligns with traditional administrative law principles that encourage public participation in agency proceedings affecting public rights, such as the registration of trademarks that could limit others’ use of common language. It seems particularly on-point in this case involving “Rapunzel” where the harm comes from potentially chilling public use — such as an elementary school puppet show performance fable. Likewise, when consumers search for “Rapunzel dolls” they are using those terms for their descriptive meaning, not to identify particular manufacturers. But, who is going to challenge a bogus trademark if it doesn’t materially harm a competitor? The court here seems to have created an enforcement gap — we’ll see if the Supreme Court is willing to fix it.

= = =

It is also interesting to consider that the Patent Act’s IPR statute also uses the “any person” standard — but thus far no additional standards have been imported to limit the scope of coverage.

I’ve seen patent attorneys file patent applications on their own “inventions” and get what I feel is discriminatory treatment on patentability questions. It seems that such “inventors” are seen as “trolls” looking to make a buck off of infringement litigation later, unless they can really show they have started a legitimate business. This case feels similar, with the sentiment: “don’t let the lawyers insert themselves as parties into the business of the USPTO.”

I’ve seen patent attorneys file patent applications on their own “inventions” and get what I feel is discriminatory treatment on patentability questions. It seems that such “inventors” are seen as “trolls” looking to make a buck off of infringement litigation later, unless they can really show they have started a legitimate business. This case feels similar, with the sentiment: “don’t let the lawyers insert themselves as parties into the business of the USPTO.”

Thank you for this explanation. It just seems wrong that one company can take a famous character in the public domain, and gain exclusive rights to marketing likenesses of that character. When Mickey Mouse’s first copyright ran out last year, was it then possible for someone else to jump in and effectively re-start it in their own name? I know little about copyright law, but that sounds wrong. If Disney had applied for a trademark registration on Steamboat Willie, what would have happened? There’s a lot of things more important that this one little thing, but still.

A blatant case of the Court rewriting the law to suit its biases.

Which “Court” and which “biases”?