KSR v. Teleflex (Supreme Court 2006).

KSR v. Teleflex (Supreme Court 2006).

By Dennis Crouch

The first round of briefs have now been filed in the much anticipated KSR case that will address fundamental questions of patentability. [Copies of briefs are found below] The doctrine of nonobviousness ensures that patent rights are not granted on inventions that are simply throw-away modifications of prior technology. Questions of obviousness are at play in virtually every patent case, in both proceedings before the USPTO and during infringement litigation.

Obviousness has always been a “squishy” term, but over the past twenty-five years, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has developed a somewhat objective nonobviousness doctrine using a teaching/suggestion/motivation (TSM) test. According to the test, when various pieces of prior art each contain elements of an invention, the prior art can be combined together to invalidate a patent on the invention only when there is some motivation, suggestion, or teaching to combine the prior art.

KSR has asked the Supreme Court to rethink that approach and take a fresh look at the obviousness standard for patentability. The petition questions whether obviousness should require any proof of some suggestion or motivation to combine prior art references.

Question Presented: Whether the Federal Circuit erred in holding that a claimed invention cannot be held "obvious," and thus unpatentable under 35 U.S.C. sec. 103(a), in the absence of some proven "'teaching, suggestion or motivation' that would have led a person of ordinary skill in the art to combine the relevant prior art teachings in the manner claimed"?

Interestingly, the Supreme Court has not heard an obviousness since well before the founding of the Federal Circuit. In that case (Sakraida 1976), the Court held that a combination which only unites old elements with no change in their respective functions is precluded from patentability under 103(a). Under the Sakraida standard, the Teleflex patent is arguably obvious. In an article several years ago, Professor John Duffy identified this obviousness issue as one that should attract the Supreme Court’s attention.

[The Federal Circuit’s suggestion] test, which tends to make even seemingly trivial developments patentable, is entirely the Federal Circuit’s product. It has no basis in the Supreme Court’s case law and may, in fact, be inconsistent with the Court’s most recent pronouncement on the subject (though that precedent is now more than a quarter century old).

Duffy, The Festo Decision and the Return of the Supreme Court to the Bar of Patents, 2002 S.Ct. Rev. 273, 340-41 (2003). Now, Duffy, a former clerk of Justice Scalia, is part of the KSR team that is trying to change the rule of law.

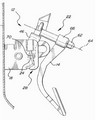

The case itself concerns a patent covering a gas pedal for an automobile. KSR makes pedals for GM & Chevy trucks and was sued for infringement of the Teleflex patent.

Crouch’s notes: In my view, the question is not correctly presented because it focuses on the aspect of “proof.” Of course any decision on obviousness should be based on some sort of proof. I expect that the Court will, as they often do, ignore this particular question and instead answer the broader question of how “a court should go about deciding whether matter claimed in a patent should be deemed ‘non-obvious' subject matter.” In fact, in its merits brief, KSR implicitly recognizes this more fundamental question in its summary of the case.

It is very likely that the Federal Circuit’s home-grown TSM test will be eliminated. This leaves us with a gaping hole — the most likely successor is a return to Sakraida that would require a showing of some functional-shift caused by a combination of old elements.

Petitioner KSR and a group of amici have recently filed their briefs on the merits. Looking at the Amici thus far, you can see that KSR’s supporters are primarily law professors and large companies likely to get sued for patent infringement. They are hoping to lower the obviousness standard — making it easier to invalidate a patent during litigation. It is not clear, however, that the Sakraida standard is actually a higher patentability bar — that all depends on the meaning of a “functional-shift.” That said, many of the potential defendants will be happy if the law becomes more unsettled — the result at least gives them more reason to appeal and would thus increase the plaintiff’s litigation costs (marginally lowering the number of infringement suits filed). Notably, none of the major bar associations support the petitioner.

What follows is a brief review of those documents. The original documents themselves are accessible through links at the bottom of the article.

Petitioner KSR’s Brief

KSR’s strongest case is that the way the courts determine obviousness today (the TSM test) is not based on any statutory language nor is it based on any Supreme Court jurisprudence. Rather, the CAFC has created the TSM test out of whole cloth and crafted it in a way that inappropriately rejects Supreme Court precedent. The extremely well researched and written brief traces the history of obviousness jurisdiction and uses that history as the primary basis for its conclusions.

One interesting argument is KSR’s position that provides 103(a) a condition for patentability rather than a condition for challenging patentability. This appears to be an argument directed primarily to patent prosecution — that the applicant should be the one making an up-front showing of non-obviousness to satisfy section 103(a) rather than the PTO being forced to open with its rejection.

Finally, KSR makes clear that the TSM test sets the patentability bar too low and allows too many technically trivial inventions to receive patent protection.

The only thing lacking here is any strong guidance for what obviousness test should arise to replace the soon to be displaced TSM test. KSR argues for little more than “adherence to [the Court’s] precedents.” The result will certainly be a number of years of turmoil — especially on the side of patent prosecution.

Bush Administration in Support of Petitioner

The Government argues that the CAFC has “inappropriately broadens the category of nonobvious and therefore patentable inventions” by limiting the obviousness determination to a single rigid test. Rather, the Government would return to the rules of Graham v. John Deere, that try to determine “whether the claimed invention manifests the extraordinary level of innovation, beyond the capabilities of a person having ordinary skill in the art, that warrants the award of a patent.”

In particular, the brief points out that the TSM test is not wrong. Rather, the problem is that the TSM test should not be the only test available to determine whether an invention is obvious. For instance, the Government argues that PTO Examiners should be able to reject claims based on their “basic knowledge” or “common sense.”

Law and History Professors (Sarnoff) in Support of Petitioner

Professor Sarnoff along with six other professors add to the debate by recognizing that the Supreme Court’s precedent, although “sound,” needs to be clarified: The professors

suggest [as a clarification to Graham] that the Court hold that the obviousness inquiry is designed to prohibit patents on inventions that could have been made by those skilled in the art within a reasonable period of time (following the time that the invention at issue was actually made) and within reasonable budgetary constraints.

The professors also suggest several modifications (clarifications) of the burdens of proof of patentability. Their first suggestion would be to remove the evidentiary burden on the PTO (or challenger in litigation) to satisfy the TSM test. Thus, even if the TSM test remains in effect, the initial burden would presumably be shifted to the patentee to prove that the test is not satisfied.

Another clarification would relate to the presumption of validity.

[T]he Court should clarify that a clear and convincing burden of proof should not apply to issues for which the relevant evidence was not previously considered by the Patent Office.

Progress and Freedom Foundation in Support of Petitioner

PFF is a think tank that supports free markets and usually strong property rights. (Richard Epstein and John Duffy are both members of PFF advisory counsel). A strong property regime in the patent system means that issued patents should be valid and should clearly show their scope of coverage. PFF’s contribution is to explore how improper hindsight can be avoided even without strict evidentiary requirements:

But adopting the correct standard does not require that USPTO or the courts give in to subjective whim, because there are administrative mechanisms that can be used to make the exercise of subjective judgment fair and reasonably consistent over time.

For example, USPTO could adopt the current Federal Circuit test as a first cut, because it does indeed represent a crucial benchmark. Any invention which fails the “teaching-suggestion-motivation” test is clearly not patentable. But this need not end the inquiry. If the examiner thinks he/she has a special case in which this test does not capture the reality of the situation, perhaps the matter could be referred to a multiperson review committee, thus eliminating the influence of a single examiner’s whim. Or perhaps boards of outside experts could be established, or community peer review processes conducted over the Internet.

Documents:

-

On the Merits

-

In Support of Petitioner

-

Petitioner's Brief on the Merits; [UPDATED WITH CORRECT VERSION]

-

AARP.

-

-

In Support of Neither Party

-

-

Petitions Stage

- Party Briefs

- KSR’s Petition for Cert (Including the CAFC and District Court decisions in Appx. A & B);

- Teleflex’s Brief in Opposition;

- KSR Reply Brief (314 KB);

- Teleflex Supplement.

-

Amicus Briefs

- Party Briefs

Links:

- Discussion of Government's Brief in Support of Certiorari;

- Discussion of Microsoft’s Amicus Brief;

- Discussion of the CAFC decision;

- Discussion of Law Professors Brief;

- Discussion of In re Kahn;

- Discussion of Petition for Certiorari;

- Prediction Certiorari;

- Prof Miller: KSR Lift-off!

- Prof Miller: Discussion of Gov’t Brief;

- Patent Hawk: Becoming Less Obvious;

- Patent Hawk: Hindsight Problem;

- Buchanan: "[O]nce again, patent reform has left the Capitol and walked across First Street to the Supreme Court." [Link];

- Petherbridge & Wagner Empirical Article [link]

- Cotropia Article: [link].

- The Patent at issue: [link]

Cite as Dennis Crouch, “KSR v. Teleflex: Rethinking Obviousness,” Patently-O, available at https://patentlyo.com/patent/2006/08/ksr_v_teleflex_.html

I agree with the previous writer that what was or was not obvious at the date of the claim is a question of fact, not law. That’s what the Supreme Court of Germany used to say. But now the BGH has decided that it is a question of law, to be reviewed on appeal. The only explanation I can find is political. The BGH is making a competitive bid within Europe to distinguish its civil law jurisdiction (court plays the role of PHOSITA) from London’s common law jurisdiction. It is announcing: If you are the sort of litigant who wants to have a second bite at the apple (first instance as dress rehearsal for the main action on appeal), Germany is the jurisdiction for you.

Isn’t forum-shopping wonderful, and isn’t Europe a worthwhile place to study, when contemplating what directions US patent law should take?

John Darling: “To one of the previous posters, obviousness is not a question of fact. It is a question of law determined by analyzing findings of fact”.

This is a large part of the problem with obviousness in the US. Elsewhere, obviousness is clearly considered to be a question of fact, and is even routinely described as a “jury question” despite not being determined in front of a jury…

An admission that this is so, as some of the CAFC judges are clearly desirous, might go some way to helping the SCOTUS craft an appropriate test.

Luke Ueda-Sarson

It seems that if the Supreme court raises the bar on obviousness, then prosecutors will be forced to write even MORE obfuscated and even LONGER specs. After all, if things are written clearly and succinctly, they MUST be obvious.

The more obfuscated things are, the more difficult it will be to use hindsight and invalidate a patent. Thus, there will be a trend to use more techno-jargon and legalese.

If things are laid out clearly, then any non-scientist/non-engineer, even the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, will get a good understanding of the invention, and conclude that it is obvious.

This is a continuation of a trend that began about 5-10 years ago – with newer patents, someone who wants to learn the teachings of the patent can not just look up the “object of the invention” and figure out, within 90 seconds, what the patent is about (like you can with many older issued patents).

Of course, everybody would agree this is bad trend – i.e. the public gets denied a clear disclosure.

Personally, as a prosecutor, I am bound to protect the interests of my client. If writing an obfuscated spec reduces the chances of some judge deciding that my client’s invention is obvious, then so be it.

GENERAL OBSERVATION (law of unintended consequences) – much of the weakening of patents – due to (A) past and current events, such as court decisions where the court reads limitations and inventor observations of the spec into the claims (today, when we write specs, anything we say can and will be used against us) as well as (B) possible future events (for example, proposals to eliminating the best mode requirement, to raise the bar on obviousness) has lead, and will lead, to worse disclosures for the public.

Another example is the intentional obfuscation that will become common if the courts decide that business methods are not patentable subject- matter (or if they “raise the bar” for patentability of business methods). Then, prosecutors like me, will be forced to rephrase business method claims as “technical” computer (or other) claims (and, concomitantly, to write the spec differently). The result will also be a disclosure that is more difficult to comprehend.

Thus, the spec will technically be “enabling” but will be a much less useful disclosure.

ANOTHER MUSING – if the dreaded “proposed rules” are implemented, it will be interesting how the “overlapping specifications filed at the same time” issue plays out. I foresee a scenario where an Applicant can write duplicate specs, where each spec is obfuscated differently. This would allow the Applicant to claim that the specs do not overlap to get a shot at more “continuations” and/or a chance to have more claims examined. I admit this scenario is a little far-fetched and crazy, but so are the proposed rules.

ANOTHER DETRIMENTAL EFFECT – only the rich corporations will have the budget to pay for patent practitioners (like me) to obfuscate their patent application.

Dennis et al:

Why are all of submitted documents in support of the petitioner, or neutral? None of the documents with links listed above is in opposition to the petition.

The SC needs to hear both sides of the story. As noted, the SC has little knowledge of patents and zero knowledge of engineering or science.

A plea: would some of the experienced clear thinkers who posted comments above do so in a way that those comments come to the attention of the SC? If it is too late to participate in the court filings, then send a (jointly authored) op-ed piece to BOTH the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times.

POINT 2: Tom stated:

“The deep difficulty here is that the very framing of the problem may indeed be the most significant leap of creative intuition in the invention.”

The inventive step is indeed often identification of a problem, or defining a problem in a new way. Once the problem is identified, a solution may be evident. But if the inventor had not identified the problem, no solution would ever be suggested by anyone.

This “identification of the problem” type of invention is common and important, and this type may be the most threatened by abandonment of the TSM test. It will become extremely difficult to obtain patents for things that truly seem non-O.

I have a copy of Peter Woit’s book “Not Even Wrong” which contains a criticism of string theory. The title, of course, is taken from the famous remark by Wolfgang Pauli about work that is in so undeveloped a state that it cannot be used to make a testable prediction.

So if we apply the Pauli approach to sets of features brought together in a claim, we might classify them as:

(a) An inventive combination;

(b) An obvious combination; and

(c) Not even a combination.

Thank you, Mr. Crouch, for the detailed and useful analysis on nonobviousness in US jurisprudence. And, also thanks in advance for my referring to your column in my blog. link to patent-japan.blogspot.com

John – thanks for picking up my loose language.

I wasn’t saying that we should remove all tests, only that a single test shouldn’t be applied slavishly to every situation.

Thanks for clarifying -goes to show how the obvious can sometimes be viewed in a relative and ambiguous manner if not instructed or directed- better send all patent examiners and their overseers to the same school of retooled thought if the test for finding if it is there changes.

Actually, my reference to the “bull” case could be aptly characterized by a claim such as:

A device for removing the “privates” of those “intellectuals” who proffer opinions ad nauseum on the construction of the patent laws, said device consisting of….

It is difficult, if not impossible, to demonstrate utility under 101 for an invention that has no possible use…..

I think you get my drift.

My advice to the Supreme Court is beware the “It’s so obvious nobody ever bothered to disclose it, let alone write it down anywhere” argument. That’s a slippery slope you don’t want to set foot on.

As a native of New London, I must sadly agree with Gideon. The assault on individual property, both real and intellectual, continues unabated. I guess many won’t be too upset by that. Until it’s their property under attack.

To one of the previous posters, obviousness is not a question of fact. It is a question of law determined by analyzing findings of fact. The vast majority of examiners do not perform even a semblance of analyis, let alone fact finding, and simply conclude that an invention is obvious because they have found a plurality of references that include all the claim limitations (if they even manage that). Without some objective requirement for combining the references, what you have is the prevailing standard of obviousness in the examining corps: it’s obvious because I say so.

Reading arguments about obviousness by law professors is a nice break from prosecuting patent applications, but I really should get back to getting my clients’ applications allowed before their views actually become binding precedent.

Ha-great reference Slonecker, but did you make it as a subjective disemination of the actual patent persecution of the device or a more sinisterly sublime approach at humor only- the attemt to take the ‘balls’ off of the patent system as it now stands-sometimes the obviousness is not so apparent.

This case is like an impending train wreck. Those of us who prosecute patent applications are hoping that at the last minute the train will be switched onto another track.

Given that most inventions are combinations of old elements, simply because most elements are old, some test is needed as to whether PHOSITA would have combined those elements at the time, and the old cases that KSR want to re-assert don’t provide us with any workable test.

Maybe the SC will give us a new test, that may or may not be workable, or maybe some over-complicated combination of TSM with other factors, but worst of all they could return us to the status quo ante, maybe not just ante TSM, but ante 1952.

As for the PTO hiring PHOSITA, that is actually what they try to do, and they call them Examiners. A PTO examiner is not PHOSITA, and cannot be, because he or she is in the PTO examining applications instead of working in the art. However, the same will be true of any experts they hire, unless they continue to work in the art and therefore have a conflict of interest that would bar them from the job. This suggestion comes up over and over, but those who propose it haven’t thought it through.

If the TSM test is thrown out, what happens to the ‘substantial evidence’ requirement? (Zurko and In Re Sang Su Lee). Maybe it will become more important.

Good post Slonecker.

Gave me a reason to research Solomon and Callicrate.

Solomon was easy.

Callicrate was tougher because there was a typo (no “non” before “infringement”) in the infringement section at this link . . .

link to patentlyo.com

But after reading the case with my lawyer glasses, I had to take the glasses off before I finally got the castration joke and the utility reference.

Good form, sir!

Which reminds me . . .

I love the Internet (thanks Al), and I wonder how long it will be equal access and unfettered access.

“Perhaps I’m just old and jaded.”

Hardly. Just observant and experienced.

In the words of the famous contemporary philosopher Frank Zappa:

“The United States is a nation of laws: badly written and randomly enforced.”

Perhaps those who decry the incremental emasculation of our patent laws could invent a device specifically for “intellectual academicians” and “judicial Solomoms” along the line of the device in Callicrate v. Wadsworth. Whoops…bad idea. It would never get to the “anticipation” and “obviousness” tests as it would never pass the one for “utility”.

I will make one prediction that will DEFINITELY become true (100% cert).

That wretched accelerator pedal drawing will become as familiar to future generations of patent law students as the plough drawing in Graham v John Deere.

So learn to love it (or hate it)!

Wow, so much analysis. Reminds me of law school. Every kid in the class would lay out the rationale as to why their conclusion was correct. Then the kid would stand there as if a mathematical proof had just been shown. Ironically, only the future patent folks in the room could solve 2x=14+10.

Perhaps I’m just old and jaded.

I think, as always, the SC will do whatever it darn well wants.

Precedent? Please. The SC doesn’t apply precent – ever.

Who’s backing Deere? A big mess of an opinion with no real test.

First we do this. Then we do that. Then we do this. Then we do some other thing. Then we see if it’s obvious.

At the level of prosecution, that just results in Examiners writing, “obvious cuz I said so.”

So you come up with TSM.

Does it follow SC precedent? Darned if I know, because I think Deere is Deere Crap that doesn’t do much to objectify the test.

What, you don’t want an objective test?

Some poster up top wrote that the PTO should be given the budget to hire POSIA. Hah! That’s genius. It isn’t enough of a cluster f____ already, let’s throw a bunch of money at it.

But you know what this really all comes down to?

Have you been reading the writing on the wall?

Come on, get your heads out of your law school trained a____s and look at the bigger picture.

First you have New London. That case was a patriot missle over the bow. It said to average Joe American, who wasn’t listening, “you think you have a right to your own property? Hah!!”

Then there was the last SC patent decision. Apply conventional injunction test. They said.

What’s the result? The result is that large corporations and other money backed entities just got a huge gift. Some pesky small inventor with a big idea and a little wallet keeping you from making money on a great idea – his idea! – with a patent? Get a non-infringement opinion and crank up the production machines!! At worst, you’ll pay a royalty that’s less than what you would have paid for the rights before the SC stepped in, and no more than your profit in any case!

Welcome to America circa 2006, where corporate interests can buy whatever legislation they want, if the price is right.

Pesky home sellers trying to reduce your 6% commission by using discount brokers? Pay the lawmakers to pass a law forbidding anything but “full” service to “protect” those consumers from themselves.

Only making a dollar on each circuit breaker you sell? Pay the lawmakers to pass laws making “arc fault” circuits required by code – Ca Ching!

And yes, patents are not immune.

Pesky small inventors, Intergraphs, small companies making life difficult for you by filing applications on things you either hadn’t thought of or hadn’t thought enough of to file?

Label them trolls, get over-educated but under-experienced professors to back you, get mega corps to jump on board, and then go to a personal-property adverse Supreme Court filled with leftists who want social property and rightists who wan corporate domination and what do you get?

You get an obviousness “standand” that, no matter what words are used – and there will be many many used – will amount to a

“because I said so” standard.

This is going to be a nightmare and I sure hope my options bets pan out in the next 36 months so that I can get out of this mess that’s called patent law.

Dennis – great post on a great blog.

In the end, obviousness is a question of fact, right?

So, perhaps there should be caution about relying on a particular test, rather than going back to the words of 103 and assessing (by the most pertinent means applicable to the facts) whether:

“the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art…”

R&D Engineers and Scientists often conduct research experiments (e.g. by means of Design of Experiment, DOE) by combining various technical elements/features together in novel configurations/interactions without actually having or needing any particular motivation to do so. The pure intent on the part of the Engineer is merely to have a chance to analyze the subsequent experimental results to see if any actual “motivation or suggestion” found for pursuing in the direction of one or more of the combinations. Upon which, further more focused experiments can then be performed.

Shouldn’t “obviousness” be based upon whether a person skilled in the art would be “motivated to at least to conduct a given experiment (without undue experimentation) to see if whether there would then be any motivation to combine based upon the obtained experimental results ?

Dennis, I believe you’ve nailed it. One reason we have an easier standard (somewhat anyway, I’m not convinced that it really is any more difficult to get a patent in the EP) than the EPO is the same reason we require natural persons to be inventors and applicants: individual rights. The “trolls” are asserting individual rights made possible by the contingent fee.

Want to address the real problem, address contingent fee litigation, not the patent system that individuals and entrepreneurs are taking advantage of.

John,

Are you really claiming that the concept of zero was, indeed, obvious, though novel?

In other words, despite the historical record showing that legions of brilliant mathematicians in Greece and Rome did NOT hit upon the idea, nonetheless it’s obvious?

Honestly, this is why I can’t take seriously the arguments from many of those who would undermine patents on the ground of their “obviousness” — nothing’s easier to do than to declare something obvious because it seems so (after the fact of course) according to one’s personal prejudice.

I’ve heard, for example, people claim that every idea in software is obvious. I mean, EVERY idea!

The sense that something is obvious is one so fraught with ideology and bias and subjective randomness that I fear how obviousness might get decided if it is unfettered to clear documentation and evidence. And it does my fear little good to place that decision in the hands of a committee either. People in groups can as easily push each other in an extreme direction as they can cancel each other out.

My cryptic response for the day: The issue that drives all of this really a change in access to the courts.

Tom wrote:

“An example I often think about is the invention of the concept of zero — an idea that any 7 year old can readily understand, yet which somehow escaped the very best minds of the Greek and Roman eras. How did the genius Archimedes, for example, fail to hit on such a seemingly trivial insight?

In hindsight, the concept of zero could not seem more obvious. But history demonstrates beyond serious dispute that it was not.”

The concept of zero would be considered NOVEL as there would have been no precedent. The issue of OBVIOUSNESS being discussed here is that the trolls are getting away with patents that, borrowing your analogy, claims the number “1.01” after the decimal system teaching a number such as “1.1” has been established.

KSR Top-Side Briefs

Akin represents the respondent in KSR v. Teleflex, which involves the proper test for deeming a patent invalid as “obvious.” August 22nd was the due date for the petitioner’s merits brief as well as amicus briefs in support of the…

Congratulations on your continuing excellent coverage of this important topic.

There is a big difference between this case and Festo.

In Festo, the briefs filed gave the Supremes a menu of essentially three well-defined choices from which to select:- absolute bar, flexible bar or foreseeable bar.

In the present case my very rushed reading of the briefs has not shown a similar range of well defined choices. If the parties or the amici are not satisfied with the obviousness test as it stands, then what do they wish to put in its place? Although the Supremes are highly intellegent people with long experience in the law, they are not experts in patent law and presumably also for the most part lack scientific training. To expect under these circumstances that they will come up with a better test unless they are given simple, sensible and well-defined choices is not rational.

The collocation/combination test is not anything new. It has been around since the 1880’s at the least, and provides that when a patent attorney assembles a group of elements into a claim, they are only recognized as a group if there is some new function or result that flows from the group and is not just what the individual members do. Just like runners in a track event are individuals, but footballers are a team because they exhibit a collective behaviour. Not rocket science, nor an unreasonable demand to make of inventors. Once an attorney is attuned to look for such new behaviour in the inventions brought to him by his clients, it is easy and routine to find it.

Inventive step determination depends on the application of a few simple rules to a factual situation, the rules defining profitable lines of factual enquiry to enable an appropriate determination to be made. It is not some strange, mysterious and difficult task as some allege. Nor should it involve a high standard, a low standard, a flexible standard or a soft, furry and cute standard. It should simply be an objective standard based on the constitutional power to promote the progress of science and the useful arts by securing for limited times to inventors the exclusive rights to their discoveries. There is a very close connection between the constitutional standard of discovery and the new function or result that flows from a true combination of integers.

It is not rocket science to suggest that claims should be subject to preliminary scruitiny to see whether there is some novel collective behaviour to be found from the claimed elements as a group which might stand as a discovery by the inventor. If the claim does not pass that hurdle, then anticipation or obviousness of the individual elements is anticipation of the group. If it does pass that hurdle, then novelty or obviousness must be considered for the group as a whole and there is not much wrong with the motivation to combine test applied by the CAFC.

It is a matter of experience that if a claimed combination of elements does indeed exhibit a new and unexpected collective behaviour (an advantageous new function or result), then a claim to that combination is likely to be invalidated for lack of inventive step in only a small minority of cases.

The neutral IBM Amicus suggestion appears the most workable solution to this old PTO practitioner, and I would be interested in comments from others.

My sole hope is that the case be treated in a more thoughtful manner than was the case in Sakraida v. AgPro. One need only read “The Bretheren” to understand what I mean.

Linguistic gymnastics aside, I have yet to read a compelling argument for eliminating the TSM approach. Let us not loose sight of the fact that not every inventor is a rocket scientist. Many are simply hard working stiffs who come up with what they think is a better idea, and to adopt an obviousness standard/test markedly departing from TSM may very well disenfranchise then from the process altogether.

In my view the system works best when it is available to all inventors, those who score perfectly on the SAT, as well as those who may have never gotten past grade school. I shudder to think the law might regress back to the point where seemingly trivial inventions are denied protection based upon the random presentation by examiners of a multitude of references showing discreete elements whithout any showing how/why they render a claimed invention obvious. My personal record for a trivial device was eight printed documents from trivial to esoteric arts, together with an affidavit from the examiner that he believed he had once seen one of the recited elements being used in what he seemed to recall was a related context.

**Nothing in the statute precisely defines the term “invention”. Is it “fire of genius” or simply “conventional problem solving” that can be expected from “many” (albeit not every) ordinary engineers or people skilled in the art. Defining “invention” (and thus obviousness) will be entirely within discretion of the Supreme Court. Do not expect any thorough statuary or legislative intent analysis. This is purely going to be a policy setting decision.**

35 U.S.C. § 103(a) states that “[p]atentability shall not be negatived by the manner in which the invention was made.” Thus, I read the statute as stating that an invention could be based upon the recognition of a problem, such that one the problem was recognized, the solution to the problem would have been readily apparent. Alternatively, the invention could have been to use a known device/method/material in a manner completely different than all other prior known uses (i.e., thinking outside of the box). Also, the invention could be to take known elements and combine them in a manner that has never been done before.

In my opinion, for the Supreme Court to define “invention” by selecting one (or more) of these above-mentioned paths to invention to the exclusion of others would be in contravention of the statutory language of 35 U.S.C. § 103.

I agree very much with SF above: there’s no easy way to get at the notion of obviousness so that it avoids the problem of hindsight, however dismissive some people are of the difficulty here.

The virtue of the TSM test is that it at least attempts to work from the context of what was clearly known and established at the time of the patent application. It doesn’t use the actual problem being solved to pull, in effect from a future context, a solution.

The deep difficulty here is that the very framing of the problem may indeed be the most significant leap of creative intuition in the invention. Researchers in creativity emphasize the importance of bringing together disparate elements as being constituitive of the creative act. If the problem itself, as it gets stated, already involves the express juxtaposition of these elements, then the true ground of the invention is simply analyzed away.

In general, obviousness is not itself obvious, despite what some people seem to think.

An example I often think about is the invention of the concept of zero — an idea that any 7 year old can readily understand, yet which somehow escaped the very best minds of the Greek and Roman eras. How did the genius Archimedes, for example, fail to hit on such a seemingly trivial insight?

In hindsight, the concept of zero could not seem more obvious. But history demonstrates beyond serious dispute that it was not.

Nathanael Nerode wrote, “Hindsight is frankly easily avoided, by reading the ‘problem’ first, thinking about solutions, and then reading the solution in the patent.”

I don’t believe it’s that simple because the results of this problem-focused approach will depend upon how the problem is phrased.

Defendants and examiners will want to narrowly tailor the problem so that it suggests the solution. Plaintiffs and applicants will want to pose a broad, nebulous problem that barely points to general field of the invention.

So whose problem do you chose to read?

I suppose you could look to the text of the patent. But many patents do not pose a specific problem to be solve. Rather, they tend to provide generally problems to avoid making the solution appear more obvious.

Practioners should expect that the most immediate effect of this highly likely decision will be at the PTO Board.

**Weird. The people posting comments must mostly be patent lawyers rather than those “skilled in the art”. Why do you all love the Federal Circuit’s “Nothing Is Ever Obvious” test so much?

The TSM test as currently applied by the Federal Circuit reduces the obviousness test to the novelty test, which is clearly incorrect**

As admitted above, I am a practitioner with many, many years of experience. As a result of have probably seen several thousand real-world applications of the obviousness determination by the PTO. Based upon my experience, the PTO does not apply the obviousness standard as a simple novelty test (in fact, the position the Government is advocating in their Brief is the de facto standard already for many Examiners). When properly applied, even by the Federal Circuit’s standard, obviousness need not require “novelty” to be shown.

**You can’t eliminate the “person of ordinary skill”, no matter how mechanical you want your patent rulings to be: it’s in the law. But the Federal Circuit has effectively done just that, and that’s why there’s a dozen amici briefs attacking the Federal Circuit.**

I believe that the numbers of briefs being filed in support of KSR is not primarily fueled by a longstanding belief that the Federal Circuit has gotten the standard wrong, I believe a large number of the briefs being submitted are by people/organizations that are generally hostile to patents, and see this case as a vehicle to weaken the patent system of the U.S.

**The correct procedure is rather simple, and I’m surprised nobody’s ever tried it. The courts — and the patent office — should be given a budget to hire *actual* people of ordinary skill in the art, to evaluate obviousness … Hindsight is frankly easily avoided, by reading the ‘problem’ first, thinking about solutions, and then reading the solution in the patent. If you don’t have a prior bias one way or the other — which these experts won’t — then hindsight simply will not be a major issue.**

Not a bad idea. However, not economically feasible in the PTO, and the problem of hindsight would still be there unless you don’t tell the “expert” what solution the patent applicant came up with.

One definition of obvious is “easily discovered” (see http://www.m-w.com), not discovered after considerable thought, reflection, and research. However, I believe that some are advocating that an obviousness determination reflect more of the later and not the former.

Whether or not the Federal Circuit is in contravention of Supreme Court precedents is entirely irrelevant to the outcome of this case. At the end of the day, it’s a fair bet that the Supreme Court will review the standard of obviousness de novo, and will most likely issue an entirely new set of rules for obviousness determination.

The true question to be answered before an obviousness standard could be outlined, is “what is an invention?”. Nothing in the statute precisely defines the term “invention”. Is it “fire of genius” or simply “conventional problem solving” that can be expected from “many” (albeit not every) ordinary engineers or people skilled in the art. Defining “invention” (and thus obviousness) will be entirely within discretion of the Supreme Court. Do not expect any thorough statuary or legislative intent analysis. This is purely going to be a policy setting decision.

This is where political influence comes in to play the most. I’m deftly afraid that the awful patent troll bashing of the last several years will be taking its toll.

Weird. The people posting comments must mostly be patent lawyers rather than those “skilled in the art”. Why do you all love the Federal Circuit’s “Nothing Is Ever Obvious” test so much?

The TSM test as currently applied by the Federal Circuit reduces the obviousness test to the novelty test, which is clearly incorrect; it treats the “person of ordinary skill in the art” as an idiot. As pointed out by one amicus, it’s perverse, in that the most obvious things are those which nobody will mention, because they’re that obvious.

You can’t eliminate the “person of ordinary skill”, no matter how mechanical you want your patent rulings to be: it’s in the law. But the Federal Circuit has effectively done just that, and that’s why there’s a dozen amici briefs attacking the Federal Circuit.

The correct procedure is rather simple, and I’m surprised nobody’s ever tried it. The courts — and the patent office — should be given a budget to hire *actual* people of ordinary skill in the art, to evaluate obviousness. Of course, who these people are will depend on the specific art. Different people will have to be retained for different fields. By having the court (and the patent office) hire such people — people who presumably have no personal investment in one side or the other of the case, because they were not chosen by the litigants — you get people who are willing to do their best to objectively analyze whether something is obvious or not.

Hindsight is frankly easily avoided, by reading the ‘problem’ first, thinking about solutions, and then reading the solution in the patent. If you don’t have a prior bias one way or the other — which these experts won’t — then hindsight simply will not be a major issue.

In software, nobody reads patents, and the “inventions” in most patent applications have been developed independently by dozens if not hundreds of different groups. This should be enough to prove obviousness — but under the Federal Circuit’s “nothing is obvious test”, if nobody explicitly mentioned that it was obvious, it’s treated as nonobvious. This has to end. If the “nothing is obvious test” is confirmed, the only result will be (even more) widespread civil disobedience with regard to patents, as more and more obvious patents are granted.

I will leave the discussion as to how each of the prior Supreme Court cases should be interpreted and their relative importance the Federal Circuit’s test to others.

As a practitioner before the PTO, what I want to get a read on, based upon the comments in the recently filed briefs, is where the obviousness standard might be headed and what will be the real-world impact of this standard.

The determination as to whether or not it would have been obvious to combine certain prior art references (or modify a single reference) under 35 U.S.C. § 103 should eventually reach the question: “Why?” E.g., “Why would one having ordinary skill in the art, at the time of the invention, combine reference A with reference B, to arrive at the claimed invention?”

An identification of who is qualified to answer the question “Why?” is what the Supreme Court will eventually decide.

The Government advocates that “[t]he PTO should instead be allowed to bring to bear its full expertise — including its reckoning of the basic knowledge and common sense possessed by persons in particular fields of endeavor — when making the predictive judgment whether an invention would have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the art.” (Page 26 of Government’s Brief). In other words, the Governments wants a patent examiner to have the ability to answer the question “Why?”

Although not explicitly stated, it appears that KSR is advocating that the test should be analogous to what is being practiced in Europe (i.e., the “inventive step” approach) (see pages 49-50 of KSR’s Brief).

IBM suggests an additional rebuttable presumption test which simply states that there is a rebuttable presumption that a person having ordinary skill in the art would be motivated to combine existing prior art references with the analogous art.

I haven’t read through all the briefs, but many of the ones I have read merely state that Graham should be upheld and the Federal Circuit’s “teaching-suggestion-motivation” test should be thrown out without suggesting any alternative test.

Personally, I find the Government’s suggestion to be scary. It is no secret that the PTO has tried to introduce many new initiatives to reduce the current backlog of pending applications, and in my opinion, the Government advocating the position they did is just one of those initiatives. The real-world impact of the Government’s approach will depend upon the details, but assuming that a Supreme Court decision supports the notion that any patent examiner would be able to answer the question “Why?,” then I see an extreme reduction in the number of patents being issued and filed. I can expound upon the reasons in another post.

However, if only a few “special” patent examiners, who have been deemed by the PTO to have the requisite experience/background, are allowed to make this obviousness determination, then I see these patent examiners spread amongst the art units and either cosigning the office actions or submitting declarations, which accompany the office actions and state that the “special” examiner agrees with the obviousness determination. In such a scenario, I foresee the larger patent filers (i.e., those companies that file a substantial number of patents each year establishing comparable groups of engineers/experts, which the large patents filers will be able to draw upon, to submit declarations in opposition to the obviousness determination. Less financed or less savvy patent applicants, however, will have a much harder time finding someone qualified enough to submit an opposing declaration with regard to the PTO’s obviousness determination.

I don’t know enough about how the obviousness standard is applied at the EPO to opine one way or another. IBM’s suggestion basically shifts the burden from the Examiner to answer the question “Why?” to the applicant to answer the question “Why not?.” Essentially, this position assumes obviousness and requires an applicant to argue indicia of nonobviousness.

I agree with much of the rationale set forth by the Federal Circuit in support of the “teaching-suggestion-motivation” test. This test simply requires that the person answering the question “Why?” be “one having ordinary skill in the art.” This approach not only prevents impermissible “hindsight reconstruction” from being a factor in the obviousness determination, it also prevents prejudices against the patentee (or applicant) from being manifested in the obviousness determination. As a result, I am in agreement with the Brief filed by Ford & DaimlerChrysler.

Regardless of what new approach is selected, if the Federal Circuit’s “teaching-suggestion-motivation” test is thrown out by the Supreme Court, that approach will likely be a broadening of how obviousness is determined. I foresee the end result of such a new test for obviousness to be a rush to the courts in attempt to invalidate those patents that have economic value. Eventually, within the courts, the battle will be waged by competing experts on both sides, one side arguing that for obviousness and the other side arguing against obviousness. Within the PTO, as noted above assuming that not all examiner’s would be capable of making the obviousness determination, I also foresee a similar type of battle being waged between “hired guns” for larger companies and “special examiners” for the PTO submitting declarations as to whether or not a particular combination would have been obvious. In either situation, the true motivation of the people making the obviousness determinations will always be in question. In contrast, by relying by what was stated by those skilled in the art to answer the question “Why?”, the Federal Circuit’s test for obviousness provides not only a cleaner approach for the courts and the PTO to administer but also an approach that reduces the reliance upon the opinions of interested parties in making the determination of obviousness.

A good animation illustrating the invention and its relation to prior art produced by Demonstratives Inc. is available on the following site:

link to demonstratives.com

or use the link on my new blog for patent practitioners in Canada:

link to cestepatent.wordpress.com

Thanks Dennis for all the great posts

>>Sakraida: All elements are old and can be found by an examiner in some written document via a word search. It is obvious to unite old elements. However, if the function of one of the elements changes as a result of the uniting, then the uniting may not be precluded from patentability under 103(a).

You are absolutely correct. All that is needed is a proper understanding of “subject matter as a whole.” If there is no new “whole,” then the aggregation is not patentable.

>>For example, USPTO could adopt the current Federal Circuit test as a first cut, because it does indeed represent a crucial benchmark. Any invention which fails the “teaching-suggestion-motivation” test is clearly not patentable. But this need not end the inquiry. If the examiner thinks he/she has a special case in which this test does not capture the reality of the situation, perhaps the matter could be referred to a multiperson review committee, thus eliminating the influence of a single examiner’s whim. Or perhaps boards of outside experts could be established, or community peer review processes conducted over the Internet.

This is plain silly. The test for obviousness can be made clear by proper weight to “subject matter as a whole.” There is no need for committees to determine this.

>>Rather, the CAFC has created the TSM test out of whole cloth and crafted it in a way that inappropriately rejects Supreme Court precedent.

I think this statement is untrue. The statutory language “if the differences…are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made…” supports the TSM test. The test is the natural consequence that obviousness must be determined at the time the invention was made. This is NOT a test fabricated out of whole cloth.

Furthermore, with proper weight to the phrase “subject matter as a whole,” the Supreme Court precedent can be properly included. This phrase can easily be construed to mean that there must at least be a “whole.” If there is a claim to an aggregation which is taken together achieves no new “whole” it is not patentable.

I think the Supreme Court can easily dispose of this case by simple interpretation of the statutory language.

KSR – Briefs Support KSR, with Commentary

The indefatigable Dennis Crouch has it all, at Patently-O.

Over the next few days, as I work through the briefs filed in support of KSRs position filed this past Tuesday, I will share some excerpts and some commentary on the briefs here at TFOG….

Mark Purdue wrote: “the PTO need only make a prima facie case of obviousness, while the validity challenger needs clear and convincing evidence..”

Of course, that’s the established standard, but when it comes to TSM, PTO examiners generally get no leeway. I have never seen or heard discussion of two types of TSM; “prima facie TSM” for examiners, and “clear and convincing TSM” for litigants.

Mark writes

“I certainly don’t mind the idea of the presumption vanishing should the validity challenger present uncited, noncumulative art.”

No doubt. I would also suggest that the presumption should be removed in any case where a patent was allowed after a telephonic or personal interview with the Examiner, unless the complete transcript of the interview is provided in the file.

The answer to the above is that the PTO need only make a prima facie case of obviousness, while the validity challenger needs clear and convincing evidence. On that alone, the burden is much heavier on the litigant challenging validity than the PTO.

The presumption of validity question is a good one, for sure. It was originally based on the idea that the PTO is competent at its job and should not be second-guessed. Given the poor quality of searching (and unavailability of printed publication art in some TCs/GAUs), perhaps we should reconsider the presumption. I certainly don’t mind the idea of the presumption vanishing should the validity challenger present uncited, noncumulative art.

The Federal Circuit has erected the TSM test as a guard against hindsight and seemingly subjective input when addressing obviousness. But here’s what I believe to be a great anomaly with the CAFC uniform TSM standard and also a great anomaly in a very basic principle of U.S. patent law, i.e. “presumption of validity”:

1. The CAFC has adopted the same standard of a TSM showing for both, claims pending before the PTO, and claims that are being attacked in an infringement suit. But why? Duly issued claims have a presumption of validity (35 USC 282). Pending claims are not presumed valid. So why should the PTO, as a challenger of claim validity, be subject to the exact same standard as a potential infringer of a duly issued claim. Doesn’t the “presumed validity” of duly issued claims imply that the proof of invalidity is higher for issued claims? Current CAFC obviousness jurisprudence is defeatable by very basic statuary analysis.

2. This leads to my second question. Why indeed should issued claims be presumed valid? To the extent certain prior art was never before the examiner, and are being presented in a court invalidity proceeding at first impression, why should the burden of proof be placed on the “party asserting such invalidity” (sec. 282)? Why should the party “asserting a monopoly” be awarded this special advantage of “presumed validity”, just because a less so successful examiner, or perhaps negligent one, has missed some important prior art?

Sakraida is a very poorly reasoned opinion. It adds nothing whatsoever to the obviousness inquiry.

Graham requires the following:

Under 103, the scope and content of the prior art are to be determined; differences between the prior art and the claims at issue are to be ascertained; and the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art resolved.

TSM falls within the scope and content of the prior art and the level of ordinary skill. As the Federal Circuit eloquently stated in Gore: “The text of § 103 includes the phrase “at the time the invention was made.” It is this phrase that guards against entry into the “tempting but forbidden zone of hindsight” in evaluating the obviousness of a claimed invention. [citation omitted]. Measuring a claimed invention against the standard established by § 103 requires the oft-difficult but critical step of casting the mind back to the time of invention, to consider the thinking of one of ordinary skill in the art, guided only by the prior art references and the then-accepted wisdom in the field. [Citation omitted”

“The best defense against the subtle but powerful attraction of a hindsight-based obviousness analysis is rigorous application of the requirement for a showing of the teaching or motivation to combine prior art references.” Bard.

Can’t say it much better than that.

It is interesting that no one from Pharma/Bio had entered the debate. . .

Before reading the Briefs, a couple points from your clear summary of the briefs stand out for comment. First, the origin of the motivation test is not the Federal Circuit but dates back to CCPA law contemporaneous with the 1952 Patent Act. The test though has definitely evolved. On this point, see Judge Nies excellent concurrence in In Re Oetiker. Second, the question is to some degree about proof only because the TSM test is a question of fact that the challenger needs to prove as a threshold test under 103. Third, “basic knowledge” and “common sense” have no evidentiary support. People have been harping on these cases, but contrary to some of the briefs, the focus here is on finding proof of what the PHOSITA knows. In the PTO perhaps that is just a question of access to resources and time, especially given how easy it is ex post to decide something was common sense. Common sense is fine as long as there is some evidence to connect that knowledge to the PHOSITA, and here I think is where you inject a flavor of what’s broadly known in the art from more general references perhaps versus what is found in the specific detailed patents that teach the claim limitations. Fourth, the TSM is not the single test of patentability; it’s a threshold requirement that then triggers the legal decision based on all evidence of whether something is obvious. In the PTO, this takes the form of the prima facie case. But as the Federal Circuit has pointed out on many occassions, there are no per se rules and obviousness is determined based on all the evidence presented under Graham, especially after the patent owner has presented rebuttal and objective evidence. Fifth, Supreme Court cases are somewhat conflicting as U.S. v. Adams can be read to require some motivation and expectation of success to make the claimed combination. Sixth, there is something to be said for a distinction between a combination and an aggregation where the combination implies an interconnection of the claims elements that limits the claims while the aggregation merely puts old elements together as a package deal. But that takes more thinking and fleshing out. Seventh, some delicate consideration of the “nature of the problem” issue is required as a distinction could be made between an inventor who discovers a problem (less obvious roughly) and an inventor who solves a well known problem (more obvious roughly but secondary evidence can come in if there is a prima facie showing). Federal Circuit law on the “nature of the problem” and how it fits into the test has not been that clear and could be a key to “fixing” the TSM test, or at least clarifying it.

To make a more narrowly focused comment, does the SG’s standard of “beyond the capabilities of PHOSITA” imply that the common run of engineers are by definition incapable of making a patentable invention? Should the sign on the PTO door say, “Only geniuses need apply”? What about the concept of protecting investment in R&D?

Sakraida: All elements are old and can be found by an examiner in some written document via a word search. It is obvious to unite old elements. However, if the function of one of the elements changes as a result of the uniting, then the uniting may not be precluded from patentability under 103(a).

Wouldn’t you have to claim the function to successfully comply with the Sakraida test? And if you claim the function and the examiner found a similar function performed by different elements in another patent, wouldn’t that make the claim obvious? Or would there need to be a motivation to combine the similar function found in a patent with the elements found in another patent.

I do not see how shifting the analysis from element-element motivation to element-function motivation will solve anything.

This is a great post. Thanks for the thought and effort.

I would be surprised if the Court simply tossed out TSM and affirmed Sakraida. That move would seem to ignore the expertise developed by the Federal Circuit over the past 24 years. (I mean expertise partly sincerely and partly ironically, as is the custom nowadays.) Now, the Supreme Court and the Federal Circuit are not on the friendliest of terms, and there seem to have been a number of reversals, or slaps in the face, over the last decade or so. But at least, as Metabolite seems to indicate, there is, on the surface, some deference by the Court to the expertise of the Federal Circuit, or at least a hesitancy to move into territory where the Federal Circuit has not tread.

Nonetheless, as the SG’s brief and all the scholarly commentary and perhaps also some common sense indicate, TSM as applied is inconsistent with Graham v Deere. The approach seems to ignore PHOSITA and creates an unreasonable inference from silence in the prior art. As I think I have posted here before, the lack of TSM in the prior art could just as logically support a conclusion that the invention is obvious. Some things just may not be worth teaching, suggesting, or motivating. A more proper approach might be to ask whether PHOSITA would consider that lack of TSM in the prior art an indication of nonobviousness. At least, that approach, with its obvious problems, is more grounded in Graham v. Deere and would be consistent with the use of teaching away as an indication of nonobviousness.

There are two problems. The first is with Sakraida; the second is with nonobviousness more generally. The problem with Sakraida is that it harkens back to the bad old days of patent law, pre-1952, when nonobviousness was treated largely through a subjective standard (much like originality in copyright sometimes is treated today). To be fair, Sakraida is more grounded in the objective, PHOSITA standard laid out in Graham, but the fear is that by tossing out TSM and returning to the synergy approach, the Court would open up the nonobviousness analysis in a way that might be too unpredictable. At least with TSM, there is some predictability, even though the prediction might tend to be patents of dubious pedigree.

The second problem is that the Court might turn the nonobviousness inquiry into something akin to negligence in tort law. In fact, the Court did analogize nonobviousness to neglgience (and scienter) in Graham. Not only does that solution, lose predictability, it also guts the statute. If the Court did make nonobviousness a largely facts and circumstances inquiry, I am sure the Federal Circuit would come up with some alternative to TSM fairly quickly to restore some order. The alternative may not be much better than what we have now. I think this result is unlikely, but it is something to watch with caution.

My guess is that there will be some pragmatic solution. TSM will be tempered with the fact that prior art does not teach, suggest, or motivate the combination as one factor to consider in the analysis. I hope that TSM also gets tempered by affirming the role of PHOSITA in framing the analysis. On this last point, some common law thinking might come in handy. PHOSITA is the analogue of the reasonable person in negligence, warts and all. But the reasonable person in negligence is the person of ordinary prudence whose reasonableness becomes layered as the fact pattern calls for more expertise or specialized knowledge. I think that PHOSITA should also start with the inventor of ordinary prudence, the lay person who has some common sense of how to tinker and put things together. As the context becomes more specialized, PHOSITA can then take on the layers of expertise required by the speciality. But it would be great if the Court affirmed that PHOSITA and the nonobviousness analysis should start from some notion of “ordinary prudence” as a way to filter out patents that would make the ordinary person in the street ask, you got a patent for that?