by Dennis Crouch

At $3.2 million per dose, Elevidys is one of the most expensive drugs ever approved. The drug is used to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a fatal genetic disease that progressively destroys muscle function and kills most patients in their twenties. Elevidys represents both the remarkable promise and the profound access tension at the heart of gene therapy patents. The underlying technology was developed in the laboratory of Dr. James M. Wilson at the University of Pennsylvania, supported in substantial part by more than $105 million in NIH funding over Wilson’s career, and then exclusively licensed to REGENXBIO Inc., which sued Sarepta for using the platform technology without authorization.

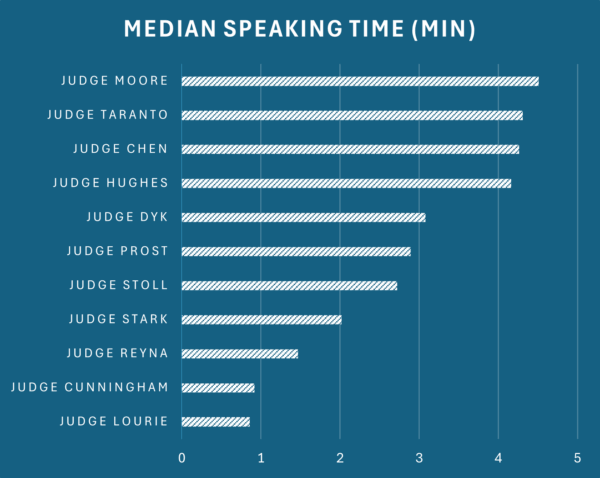

On February 20, 2026, the Federal Circuit reversed a Delaware district court’s grant of summary judgment of ineligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101, holding that the claimed genetically engineered host cells are not directed to a natural phenomenon. REGENXBIO Inc. v. Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc., No. 24-1408 (Fed. Cir. Feb. 20, 2026) (Stoll, J., joined by Dyk and Hughes). The reversal applies settled doctrine that traces Diamond v. Chakrabarty through Myriad‘s cDNA holding and Diamond v. Diehr‘s prohibition on dissecting claims into old and new elements. At the same time, the result here stands in sharp contrast to the § 101 struggles that have plagued software and diagnostic method claims over the past decade, where courts have routinely found “man made” items ineligible.

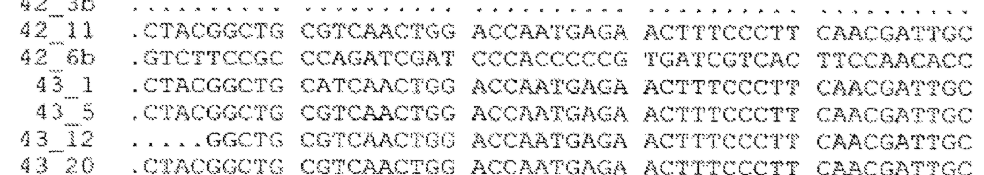

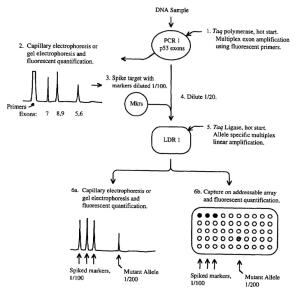

The patent at issue, US10526617, is owned by the University of Pennsylvania and exclusively licensed to REGENXBIO. The ‘617 patent expired in 2022, so this litigation was always about past damages, not injunctive relief. Representative claim 1 covers a cultured host cell containing a recombinant nucleic acid molecule encoding an AVV capsid protein having a sequence 95% identical to that listed. The molecule also includes a heterologous non-AAV sequence.”

The key term “heterologous” means derived from a different species. “Recombinant” means the molecule is created by chemically splicing together nucleic acid sequences from two separate biological sources. Thus, the claimed cells do not themselves occur in nature — but Judge Andrews still found the claims directed to a natural phenomenon. REGENXBIO Inc. v. Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc., No. 20-cv-1226-RGA (D. Del. Jan. 5, 2024). (more…)