Over 1.2 million non-provisional patent applications are pending examination at the USPTO. Of those, more than 700,000 have not received even a preliminary examination. The backlog is the source of a tremendous amount of bad publicity for the USPTO. At a recent PPAC meeting, former USPTO Deputy Director Stephen Pinkos asked an important question regarding the backlog. Namely, Mr. Pinkos asked USPTO officials to identify the portion of the backlog that can be attributed to patent applicant delays rather than to the USPTO.

The Study: To answer Mr. Pinkos question, I looked at the Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) History for 1,860 randomly selected patents issued April-July 2010. Ordinarily, a patent’s enforceable term is 20–years from its application filing-date. However, an adjustment is provided when the USPTO delays in issuing a patent. However, the PTA is reduced by patent applicant delays that go beyond the ordinary two and three month deadlines for responding to USPTO requests. To be clear, the applicant-delay offset does not account for all applicant delay, but rather only delays that show a failure “to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution.” Thus, for this study, I term the calculated applicant delay offset as the “unreasonable applicant delay.”

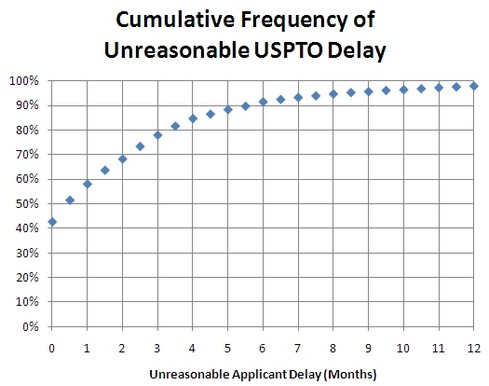

Results: The 1,860 patents in my sample had an average application pendency of 46.1 months. The average unreasonable applicant delay was only 1.9 months per patent (+/– 0.2 months). This applicant delay represents 4.2% of the pendency time for all of the patents. As the cumulative frequency chart (below) shows, a large percentage of the patents (43%) had no unreasonable applicant delay and the median unreasonable applicant delay was only 11 days. Many of the longest delays were associated with revival of abandoned applications and late submission of information disclosure statements.

The PTA history also provides a mechanism for calculating the USPTO’s responsibility for the backlog. Based on those figures average unreasonable USPTO delay is 17.5 months per patent. That “unreasonable” USPTO delay represents about 38% of the total pendency.

Notes:

-

This post was updated with data from a larger sample of patents.

Your webpage content is specifically what I necessary, I like your blog, I sincerely wish your website can be a rapid enhance in visitors, I will help you market your blog and glimpse forward for your web page continually updated and turned into even more towards the additional rich and colorful.Welcome to visit my web http://www.sneakers4sales.com

They shouldn’t exist. Wow all of a sudden it makes sense. Gee thanks Nathanael, your awesome wisdom and clear rationale make me realize the error of my ways. I can see clearly now. All that wonderful advancements in human efficiency should belong to everyone equally. I shouldn’t havet o work any more. Communism is the answer. Property is eveil. Money is evil. Everyone pitch in now and help out each other. All the world’s problems will disappear.

examiners are having a hard time stomping them out one at a time

They’re having a harder time than you think. That “utterly useless graph” was generated using issued patents only.

The “backlog” issues are wildly different within different “arts”.

As such, this is an utterly useless graph.

Long backlogs in software patents or “business method” patents are simply a sign that those patents shouldn’t exist, and that examiners are having a hard time stomping them out one at a time (because the applicants continually get to amend them), and there’s really no reason to spend more time on them if they can’t be rejected outright. Since they’re all invalid in fact.

Long backlogs in a real “useful art” would signify something different.

I suggest the USPTO hires people for art units that are fluent in language, or at least bilingual to then rewrite in English the patent application for the examiner, so he can move forward without excuses.

That’s exactly the point; the USPTO is part of the Dept of COMMERCE… we’re fast approaching a point where seeking patent protection is valueless while elsewhere in the world the US is blocked by foreign patents.

Learn some English? Good point IANAE. Actually, the world does do business in English. But not American English. Rather, it is something called “Globish”. Try this for an experiment. Watch patent attorneys from Asia, on tour in Europe, and conversing in “English” at each business meeting with their counterparts.. Afterwards, you tell me which meetings achieved the best levels of communication, and which the worst.

Would it surprise you if I were to say it goes worst in England? That’s because the English counterparts are operating in their sophisticated high level native tongue whereas, on the mainland, all participants at the meeting are using one and the same language (EFL).

ping, the point of language is to communicate effectively isn’t it?

It also follows that if you help the filing to first action phase then you automatically have a great impact on filing to issue.

As long as there are a finite number of examiner hours available, and getting an application from filing to issue takes a certain number of aggregate examiner hours on average, shifting priorities from one task to another won’t speed up the process. The work all needs to be done, and one application is always examined at the expense of another that languishes in the queue.

Cheryl, your logic is flawed.

See IANAE’s wonderful bank teller hypo.

There are two separate backlog issues happening at the USPTO. One is the time from filing to patent issue. The second is the backlog from filing to first action. Personally, I would like to see more efforts on the filing to first action phase. Before the applicant gets a first action there is little to no control on the applicant side, which is frustrating. Also after the first action at least you have some idea of what you are up against. It also follows that if you help the filing to first action phase then you automatically have a great impact on filing to issue.

What do you mean about my putting somebody competent on the case?

For a start, if they’re going to live on America’s planet they should bloody well learn some English.

ping, who said anything about being unable to examine “properly”? I was just offering you an insight into why EPO Examiners ask for verbatim support in the app as filed, when deciding whether to admit prosecution amendments. Ever heard sportsmen offering the insight that training is “harder” than the game for real? Well, when your European patent comes under attack on the ground that subject matter was added during prosecution at the EPO, you will have good reason to be grateful to that non-English EPO Examiner. Many more issued European patents would have disappeared down the fatal 123(2)/(3) trap, had it not been for EPO strictness on pre-issue claim amendments. Properly? Yes, for sure.

What do you mean about my putting somebody competent on the case? Anybody would think I give orders to the representatives of the Member States of the EPC who sit on the Administrative Council of the EPO. Or are you going to be the one to write to the Heads of State of all those Governments of countries in Europe?

If you do write, what will you urge: that the EPO be closed down perhaps?

“I don’t understand your thinking ping”

That’s obvious from your assertion that there is nothing wrong with an examiner lacking the ability to properly examine an appliction because English is not her first language. Absolutely nothing to do with the languages that courts operate in.

Or to put it another way, if an examiner cannot properly examine an application, for whatever reason, get someone on the case that can. Throwing up some inane rationale that later courts might also have trouble with language to excuse the examiner’s lack of ability to properly examine is rather messed up.

I don’t understand your thinking ping. Are you saying that it is wrong for courts in Germany to work in German, courts in France to work in French, courts in Sweden to work in Swedish etc etc?

Or are you saying that the EPO ought not to be so arrogant as to think it is competent to examine cases written in English?

What’s your solution? Should we all start learning Mandarin (and Spanish)? Doesn’t Globish work quite well, and ever better, in the real world?

“ is no bad thing, eh?”

Maxie, That’s like saying that two wrongs make a right.

…well the courts can’t read and understand English either…

Yeah, Glad, but at least in mainland Europe the courts downstream of the EPO also do their work in a langage that is not English. So a non-English rehearsal at the EPO pre-issue, is no bad thing, eh?

“As I have often posted here, there is a special reason why EPO Examiners need verbatim support. It’s because they are working in English as a foreign language.”

Now here is one point where I see the USPTO is following the EPO lead … hire Examiners who have Enlish as a second/foreign language. When a judge (in the US) is going to scutinize every word in a Markman hearing and the oppositing side is also going to twist every single word of the claim, doesn’t it make sense to have the people examining the claims understand the language at a high school level?

The words of the specification and claims are the foundation for EVERYTHING yet the USPTO hires people that have difficulties with English.

Never mind…it’s clearly addressed in the Proposed Rulemaking…just didn’t read down far enough or slow enough.

perhaps I missed, but the proposed track speed selection also be used against an applicant’s potential for PTA? I mean, say I ask for the slow-track of prosecution, does that mean I am no longer eligible for PTA even if I never take an extension?

sheba: “Right… blame the customers.”

The IRS blames its customers on a fairly regular basis. This is the government, not Wal-Mart….

Patentology–

I enjoyed your first-order approximation.

Your point that Pinkus’ original question was “a nonsense” is well received, and unfortunately accords with my own continuing criticism of the governance and administration of the patent system being undertaken by, variously, ignorant, inarticulate, and ineffective civil servants.

ping if you want a patent for the UK,you know what to do: apply to the UK Patent Office.

But if you want a patent covering the 600 million inhabitant EU then apply to the EPO. But remember how few judges and citizens in the EU have English as their first language. You are venturing onto foreign ground, right?

Still, at least the language of the EPO proceedings (English, in your cases) is the authoritative text in those post EPO grant infringement and validity proceedings.

Max, you are right about shifting inventions in midstream.

What is occurring now is similar to a home owner signing a contract for a new kitchen, then halfway through the project, the home owner says, no, I don’t want a new kitchen, I want a new living room, and I want it without paying anything extra, and I want it done by the original deadline for the kitchen, and you the contractor were supposed to figure out in advance that I would change my mind in mid-stream.

The examiner should be able to do the same thing, allow applicant to cancel the original claims, file completely new claims, expect the examiner to already have searched for the new claims, and expect prosecution to end right away, as if the applicant did not change course in mid-stream.

This is the reality that exists now. As long as applicants expect this, then the pto will have an incredibly long backlog.

Also,

Limiting what the patentee can do because of the shortcomings of the examiner is hardly serving the customer.

Language is rich and beautiful. It is the art of our craft. How much more whining must we listen to that English is a second language that limits the examiner’s ability to do her job? Yeah I realize that the old country is f’d up having a literal Tower of Babel, but perhaps yous should re-read that story and glean a lesson form it. Hint: the lesson is not about kowtowing to administrative ease.

Maxie,

Your last line doesn’t fit. It is the US patent in all its glorious and splendid technicolor that puts the black and white EPO patent to shame. The US remains the Gold standard. There is no “Gold” in the EPO black/white universe.

Ned, no time today but here’s my fantasy, why Rader J. is leary of the “European written description standard”.

Americans are horrified that the EPO requires strict verbatim support in the word strings in the app as filed for the prosecution amendments they seek to introduce at the EPO. They complain vigorously and vehemently, to anybody willing to listen. Many in the USA then suppose that you can’t have the European idea of “no new matter during prosecution” without also accepting this “strict literal verbatim” standard. Understandably, people in the USA think that is too strict. So, better not have any part of it.

The thing is, you can have Art 123(2) EPC without having the strict verbatim EPO Examiner line. You have only to go to the Boards of Appeal of the EPO to find that out. You don’t need to reflect upon the decisions in the courts in England and Germany.

As I have often posted here, there is a special reason why EPO Examiners need verbatim support. It’s because they are working in English as a foreign language. If they were examining in their native tongue they would be more confident about the admissibility of non-verbatim amendments. You see, whether a prosecution amendment added subject matter is at the heart of a lot of post-issue oppositions at the EPO, and EPO Examiners don’t like being exposed in such oppositions as having allowed an Applicant to add matter during prosecution.

But it stands to reason, in any system, that you can’t allow Applicants, during prosecution, to shift to an invention that they had not identified, as such, in their app as filed. I think it is negligent, to set sail in an app that presents as the “invention” nothing more than a detailed description of the Best Mode and a main claim hopelessly lacking in novelty. The invention (if there is one) will always lie in the undisclosed intermediate levels of generality, before you get down to the Best Mode, and exactly that is what is missing in US-drafted texts. This explains American anger about EPO “strictness” on the prosecution amendment issue.

Why should Rader J. expect such drafting? Does he ever see it, in the cases that come before him?

If you have only ever been able to see the world in black and white, can you imagine what colours are?

Right… blame the customers.

Max you are right, the solution to the backlog is quite simple, as expressed by you earlier,

“1) Require Applicants to get their claims in on day one (obviously that means careful thought about a graded sequence of dependent claims defining fall back positions in the event that claim1 is untenable). No second chance.

2) Require Examiners to get the search right first time. No second chance.”

I think that the United States is heading in this direction. First though Director Kappos will have to overcome stiff opposition from:

1) The patent bar who has endless justifications for not drafting a complete claim set, from broad to intermediate to narrow, before filing the application, and

2) Supervisors at the PTO who have endless justifications for allowing junior examiners to write second, third, and fourth action non-final rejections.

The real problems stem from two things. Attorneys don’t want to bother with understanding the scope and content of the prior art before filing. If they did, then at least some of the claims would be ready for allowance after the first action.

Supervisors at the PTO don’t want to bother with reading a rejection from a new examiner before signing it. If they did, then they would not sign bogus rejections. Supervisors should be required to do all second action non-final rejections on their own time, without help from the junior examiners. Then we will see how many bogus rejections go out the door.

Max you are right, the solution to the backlog is quite simple, as expressed by you earlier,

“1) Require Applicants to get their claims in on day one (obviously that means careful thought about a graded sequence of dependent claims defining fall back positions in the event that claim1 is untenable). No second chance.

2) Require Examiners to get the search right first time. No second chance.”

I think that the United States is heading in this direction. First though Director Kappos will have to overcome stiff opposition from:

1) The patent bar who has endless justifications for not drafting a complete claim set, from broad to intermediate to narrow, before filing the application, and

2) Supervisors at the PTO who have endless justifications for allowing junior examiners to write second, third, and fourth action non-final rejections.

The real problems stem from two things. Attorneys don’t want to bother with understanding the scope and content of the prior art before filing. If they did, then at least some of the claims would be ready for allowance after the first action.

Supervisors at the PTO don’t want to bother with reading a rejection from a new examiner before signing it. If they did, then they would not sign bogus rejections. Supervisors should be required to do all second action non-final rejections on their own time, without help from the junior examiners. Then we will see how many bogus rejections go out the door.

Ned, I cannot agree with you with regard to Judge Rader. This seems to be par for the course with you lately.

Of course, Rader sat on the Court of Federal Claims before the CAFC. He’s also a co-author of a textbook and professor for US patent law. His body of work does depict a jurist concerned with underlying patent policy, but I don’t see many instances of Rader ruling “too broadly.”

A good indicator of an overbroad or “activist” decision is if the decision becomes labelled as “in tension” with later panels on related issues. The CAFC has had no shortage of such cases in tension, but very few are from Rader opinions. (really, only Lourie comes to mind in this aspect). If anything, I get the impression that Rader actually hews closer to existing/old CAFC precedent in several areas (written description, 101, obviousness – excepting Kubin), but the court as a whole is moving in a different direction.

So, speaking of patent time to issue, delays,and the like, of couple months back there were threads about the up-tick in patents being issued every week.

Has there now been a flattening or even a drop off in number of cases issued per week as of late?

Just wondering.

Malcolm, IMHO, Rader is the perfect example of a bad judge. He has agendas that are obvious to all. He rules broadly in narrow cases. I don’t recall whether he had any judicial experience before being appointed to the court, but I doubt if he did. His mentality is that of an advocate and not that of a judge.

And no, I never applied for a clerkship.

So Ned, after you applied for your clerkship with Judge Rader, were you informed that the job was no longer available by phone or mail?

in my experience extended prosecution is desirable, even more so after issuance of a decent though narrow first patent.

Pretty much universally true, unless you got a particular unfriendly restriction and no rejoinder.

Max, thanks for your thoughtful post.

It does appear that on at least with respect to this issue, the separate written description requirement for the specification, the United States is trending toward position long ago taken by the Europeans.

Therefore, don’t you find it strange that Judge Rader found themselves in the minority in the Ariad case — essentially arguing that the only purpose for specification is to enable others to make and use that which is claimed. It appears that Judge Rader advocates a school of thought that will allow claiming subject matter disclosed regardless of whether there is any indication that the subject matter is the invention of the applicants or in any way new.

Given the wide touring of Judge Rader in Europe and his purported extensive knowledge of the European patent system, don’t you find his position here slightly strange. Isn’t this one more piece of evidence added to a large pile of evidence that Judge Rader simply does not get it rather than he is trying to move the American system toward the European system by judicial decision?

Waiting, it all depends on what you mean by “narrowing”. Time and again, I am instructed to amend in prosecution to ABCE, when 1) the original umbrella claim 1 “invention” of ABC is notoriously, egregiously, fatuously, laughably old and 2) the original dependent claim fall-back position ABCD turns out to lack novelty.

I agree that amending to ABCDE is “narrowing”, but what about that claim to ABCE?

REASONABLE

The PTO keeps using that word.

I donotthinitmeans what they thinitmeans.

They seem to thin –broadest reasonable interpretation– means ridiculously broad.

They seem to thin 3 months and two weeks is unreasonable for applicant replies but 6 or 8 months to respond to a first amendment is perfectly reasonable.

Psssst PTO: Never rush a miracle man. You rush a miracle man, you get a rotten miracle.

“If one road to issue is blocked, can you switch to an altogether different road, not claimed in the app as filed?”

Max — your hypotheticals border on the ridiculous. Try not to worry about the extremes — instead, worry about common practice.

Common practice is that if your claims are anticpated/rendered obvious, you don’t switch to a new invention altogether. Instead, you switch to a narrower aspect of the invention — which likely includes keeping the old claim language and including new limitations.

The old claim language still claimed your invention (i.e., the invention was covered by the claims) — the old claim language, however, also covered things that were not inventive. On that basis, you aren’t claiming an altogether different invention.

Ned it is true that under the EPC what you can divide out depends on what you disclose (rather than what you claim) in your original filing.

This concept of “disclosure” is at the heart of our debate for we can all agree that your scope of protection, whether in the original or in the divisional or continuation, will be limited by what you originally disclosed.

For me, the “invention”, the subject of a patent application, is more than your Best Mode. It is not an embodiment; it is a concept, enabled by at least one specific embodiment. The days of “central claiming” (claim the Best Mode) are long gone.

What you “get” from the State (the PTO, the public) ought to depend on what you ask for. I learned in my childhood that “If you don’t ask, you won’t get”.

Europe requires that you do ask, before you get. In your app as filed, which will set the date of your claims, you do have to state the concept (subject matter) that you think you have invented.

Of course, you might have to narrow down your stated concept during prosecution as closer art emerges, to get over 102 and 103. You will be wanting to narrow to a level of generality intermediate between claim 1 and your Best Mode. Even for this intermediate level inventive concept, as with any other invention, you need (in Europe) disclosure of it in the app as filed. American patent attorneys (encouraged by their caselaw) assert that this level of disclosure in the app as filed, before the PTO has searched, is impossible. The rest of the world, without such encouragement from the courts, just gets on and provides it. A set of claims written outside the USA will remind you of the layers of an onion, with claim 1 the outermost layer, and the Best Mode at the core.

But onions make you cry, right?

When the same disclosure requirement in the original parent app as filed is required by the US caselaw, then for the first time the PTO will be able to do a “right first time” search (and examination) report.

And folks will then be in a position to do clearance opinions on the basis of the WO document that will deliver meaningful results on which serious investment decisions can be made, which will encourage industry to invest more aggressively in new (job-creating) facilities, and so compete better with China.

ping, take the long summary Supreme Court cases, including Evans v. Eaton. They all require that the spec. describe the invention so that one may know what the invention is and what of the description is free to be used by the public.

Now, much of the rest of the case is about the unpredictable arts and is of very little use in the present discussion. So, I would simply refer you to the holding in Eaton. There the spec. described a machine – which was largely old. The invention was an improvement, but the spec never said what it was. The Court held this lack of distinguishing between the old and the new to be a violation of the WDR.

Now, this case has been specifically endorsed by the Ariad court. It says that the function of the claims is describe the outer perimter of the invention, but that the specification must tell us what the invention is as well.

But, and this is what you seem to miss, in doing so, the specification must also indicate in some manner what is not the invention.

So, if I now describe a system largely old where some of it is new, but do not describe what is old and what is new, I suggest such a spec would not meet the WDR per Ariad per Eaton.

Further, another reason the specification must describe what the invention is is that the inventors are swearing that that is their invention. Many times, as we all know, a great deal of what is described is old or invented by otherd. Unless it is clear what is old and what is new from the spec., exactly what it is that the inventor is swearing to be his invention is not determinable.

Later, years later in many cases, new continuation patent applications are filed claiming inventions disclosed in the specification but which were not claimed in the original claims or in any way indicated to be an invention in the original specification. In may cases, attorneys handle this by providing a fresh oath. But I would also suggest that there may be a further problem if the specification provides no hint that that subject matter was novel.

The problem obviously is this: The written description requirement is necessary to describe not only what the invention is, but to, by implication, describe what of the disclosure is not the invention and free for others to use. This purpose was repeated by numerous Supreme Court cases. Now if the unclaimed subject matter is later claimed after the public has long been using it in reliance on the fact that the subject matter was never described to be novel, a fundamenatal purpose for the requirement will be frustrated. I would suggest that the patent office could object that the claims were not supported in the original specification on the basis of a violation of the WDR even if the subject matter was fully disclosed.

In Europe, this known as “expanding the scope of the claims beyond the original disclosure.” We now, I submit, have a similar doctrine here in the States.

I lol myself.

My date for a Saturday night is Ned Heller.

Discussions on what the invention “is” in the holding don’t show your new requirement. Throw me a pincite buddy.

Not every one Ned, only those that used a bogus construction – and wouldn’t you want that?

On the point about new interpretations, that does not raise a new issue of patentablilty. If if did, every prior examination would have be reopenable after KSR.

Read the holding. It talks about what the invention “is.”

Ariad does make for some good reading Ned.

I was searching for the term “old” (that term just comes to mind naturally when I see your posts).

Guess what I found.

One single solitary use of the word “old”. And it wasn’t addressing your point above. The single use was:

“New interpretations of old statutes in light of new fact situations occur all the time.”

Rader, dissenting, quoting Lourie from Enzo 323 F.3d at 971

Now I be too lazy to find the thread where we were discussing how a 101 issue or understanding can serve as a SNQ, but this seems point on to that discussion.

I’m still searching for your ‘holding’ that there is a new requirement of “to also tell us what about the invention is new.”

Ned,

Seriously. An oath is not a search. Belief requires no search. Never has.

Interesting take there ping. Obviously, you would even repeal Section 115 which actually requires very much the same thing.

“also tell us what about the invention is new. ”

Wow Ned – that’s a stretch, even for you.

In your mind, does your statement then correlate with a requirement for the applicant to perform a search so as to be able to tell what is old?

MaxDrei, many US patent applications, particularly in the computer art, simply describe entire systems without even attempting to delineate the old from the new. Such a specification may be filed in a number of related applications where different features of the system are claimed. Alternatively, a single application might be filed with numbers of claims directed to the different features. In the latter case, typically, the patent office would enter a number of restriction requirements, forcing the various independent inventions to be filed a separate divisional applications. But regardless, it is common practice in United States to continue to claim different aspects of the specification in subsequent continuations. These later claims are not necessarily related to anything claimed in the first patent application.

I believe that European practice is not too dissimilar with respect to system-type specifications. I believe the European system will allow disclosed, but unclaimed, subject matter to be claimed in divisional applications. However, recently the European patent office requires that divisional applications be filed within two years.

This era of loosey-goosey specification writing in United States may be coming to an end with the Arriad case that requires the written description not only to describe the invention being claimed, but to also tell us what about the invention is new. This flows naturally from the Arriad court’s reliance on Eaton v. Evans, one of the very first Supreme Court cases on the written description requirement, which set forth the requirement that the specification not only described the embodiments that are being claimed, but also to delineate what was new about them. (Rader had argued that Eaton v. Evans was no longer good law as it was decided in the era prior to 1836 when there were no claims in US patents and in the only way to determine what the invention was is by reference to the specification.)

Looking at the efforts from Waiting and DC (immediately above) I suspect that the attorney world divides into those who are routinely called upon to give clearance opinions, and those who never are.

Waiting reports that, once you have seen the app as filed, you know what subject matter (claims that Applicant will belatedly set forth) you have to search (and opine upon). I know that not to be the case (even at the ultra-strict EPO).

Waiting, if you don’t know the art, you don’t know how much you might have to narrow down. On that we can agree. No dispute about that. Where we are in disagreement is in switching to a different invention. If one road to issue is blocked, can you switch to an altogether different road, not claimed in the app as filed?

6, are you there?

Waiting for the world cup to be over: How prevalent to you think it is for an applicant to be disinterested in extended prosecution without issuance. I think some applicants are single shot, get what you can, as fast as you can, and for those you might want to avoid the iterative process. For others, after an initial patent is issued, the longer the continuation takes, the better. It is so heavily dependent on the client’s circumstances and outlook, but in my experience extended prosecution is desirable, even more so after issuance of a decent though narrow first patent.

“Waiting: you tell me how the PTO is to search an invention not yet claimed.”

Read the specification? I know it is not a favored practice at the USPTO, but it does help.

“You are advocating an iterative process, right, in which Applicant won’t say what he has invented till he has seen the PTO search results on a different invention.”

I favor an iterative process. However, Applicant has already stated was his invention was — see the specification. The claims are about DISTINGUISHING the invention over the prior art. Therefore, to prepare proper claims, you need to know the prior art — which is what the USPTO is best at — knowing the prior art.

“Such an iterative process can go on for ever. That is simply the wrong balance of forces, between the Applicant and its competitors.”

Wrong — even with PTA, there is only a limited amount of patent term available. Also, the longer prosecution goes on without issuance, the less time the patent can be enforced — not desirable for applicants. Moreover, extended prosecution costs a lot of money — again, not something desirable by most applicants.

Patentology is correct: While one patentee is failing to engage, the PTO is filling its time examining applications for another patentee. so no part of the backlog is due to failure to engage.

Ray I was supposing that the PTO Examiners, like those in the EPO, will issue a Notice of Allowance just as soon as ever they can. If not, why not?

EPO Examiners get two disposal points for a refusal but only one for an allowance.

But still there is nothing they like better than to issue a Notice of Allowance, just as soon as they possibly can.

It’s a puzzle, ain’t it! My explanation is that the order of the day at the USPTO is adversarial English common law whereas at the EPO (and everywhere where English law does not hold sway) it is not so adversarial, between Applicant and Examiner. The duties borne by the Applicant’s representative are discharged differently, as between Europe and the USA.

So, I guess that the USPTO makes a mistake, if it supposes it can borrow working practices from the EPO to manage its own workload.

How about PTO “pays” for delay just like we applicants do with our extension fees? If the PTO takes longer than 3 months to respond we get a credit, discount on next ap, refund, etc.

We applicants already pay for iterations, but maybe that could go higher and higher to reward the behavior that Max suggests – getting it absolutely 100% right the first time.

Waiting: you tell me how the PTO is to search an invention not yet claimed.

You are advocating an iterative process, right, in which Applicant won’t say what he has invented till he has seen the PTO search results on a different invention.

Such an iterative process can go on for ever. That is simply the wrong balance of forces, between the Applicant and its competitors.

I’m a little confused by “identify the portion of the backlog that can be attributed to patent applicant delays rather than to the USPTO”. Correct me if I’m wrong, but once an app gets a first action, it’s no longer part of the backlog is it? I’m not aware of anything that an applicant can do to stall prosecution prior to receiving the initial action short of petitioning for suspension of the application. It seems like this article is using “backlog” when it should be using “pendency”.

Max — you suggest “1) Require Applicants to get their claims in on day one (obviously that means careful thought about a graded sequence of dependent claims defining fall back positions in the event that claim1 is untenable). No second chance.”

Unless you can tell me apriori (i) what references the Examiner is going to apply and (ii) how the Examiner is going to construe my claims, my claim drafting is just one big guess. Maybe I’ll come close, maybe not. However, no reasonable inventor is going to stake their claim on such little information.

There is a reason why prosecution is a give and take procedure. The goal is to get it right, not get it done fast. The goal is to issue quality patents, not haphazard ones. Only after both sides present their information (applicants with their disclosure and Examiner’s with their search) can quality claims be prepared.

Now go back to drinking your tea and come up with another lame idea. This one died at birth.

Why would we want to look to the EPO? They do good searches, but their examination stinks. A big waste of time going to the EPO for 95% of US applicants.

MaxDrei – as I said at the outset, the true situation is more complex. It would be possible (in theory, and given enough statistical data, which the PTO probably has) to build a queuing model of the process that takes into account all of the different queues, how they are processed, and the actual statistical variations in service times.

My simple first-order example treats all processing as equal, and assumes that arrivals of work and rate of processing can be modeled using only a single average for each.

If examiners have a fixed maximum number of hours in total to dispose of each application, and this clock can be reset by filing a continuation or an RCE, then the PTO process is roughly analogous to my simple bank example. You basically get the examiner’s time twice, and if you’re not happy you pay another fee and rejoin the queue like any other arrival.

Query to Patentology: why categorise continuation work as “new” work? I had thought it more akin to your “filling in a form” type of work. The “total time” taken for the negotiation process between attorney and PTO is the time it takes to get to the point when Applicant rests content and has no remaining urge to haggle, by filling in another form.

My solution:

1) Require Applicants to get their claims in on day one (obviously that means careful thought about a graded sequence of dependent claims defining fall back positions in the event that claim1 is untenable). No second chance.

2) Require Examiners to get the search right first time. No second chance.

3) Install effective ways for competitors to have patentability assessed by art not known to the PTO Examiner.

But what to do about the howls of anger, from the Applicant community? By and large, they are not the ones whingeing about the backlog, yet they are the ones who get hurt, when effective backlog-trimming measures are introduced. Compare what is going on at the EPO, these days. The community of Applicants, of course, are the ones who pay the salaries of the PTO employees, so the PTO will not want to upset them.

Thanks for the stats, Dennis. Interesting and thought-provoking.

Analysing the backlog is really quite a complex problem in queuing theory (google it). However, a very simple analysis suggests that applicant delays can never be the ultimate cause of backlog. Let me attempt to explain.

The PTO is a pipeline. Applications go in one end, and disposals come out the other. At any given time, there is a finite length queue of work waiting to be done. It is exactly like standing in line at the bank: if there are six people in front of me, two tellers, and the average time taken to serve each customer is three minutes, I can expect to be served in nine minutes (on average).

The queue at the bank only gets longer if new customers arrive faster than existing customers are served – more than one every one and a half minutes in my example.

Imagine the queue grows to thirty people during the lunchtime peak. That’s 90 minutes worth of work, with two tellers — a 45 minute wait for the person at the back of the queue.

Now image that as things start to slow down, there is a period during which the arrival rate of new customers is exactly equal to the service rate. Obviously the queue stays a constant length.

Now suppose that some customers have to be served twice, because they have forms to fill in, but still with a total average service time of three minutes. They spend their first period with a teller, collect their form, and then go over to the desk to fill it in. When they have finished they rejoin the queue to be served again.

Now, here’s the bit to get your head around: once a customer has collected their form, we know that they will rejoin the queue and eventually consume the remainder of their three minutes of teller time, ie this pending work is still “in the system”.

In fact, it makes no difference whether they rejoin the queue immediately and fill in the form while standing in line, or if they are entitled to rejoin the queue at the head after completing their form, or if there is a separate queue for returning customers that gets priority.

Whatever “returning customer” policy is employed, in the “steady state” (arrival rate equal to service rate) the queue does not get any longer. The average time spent waiting remains the same. A customer who takes 20 minutes rather than 5 minutes to fill in their form only delays themself by 15 minutes. This has no effect on the average time that any other customer will spend waiting.

In short, applicant delays cause their particular applications to have longer pendency, and to have reduced PTA, but have absolutely no effect whatsover on “backlog”.

Dennis’ data is interesting, because it tells us how much of the “pipeline” delay experienced by an application is, on average, due to applicant delay. It can probably also tell us roughly how long the “internal queue” is at present, as opposed to how many people are metaphorically sitting at the desks filling in their forms. But Mr Pinkus’ original question was a nonsense.

There is one and only one cause of backlog – arrival rate of new work exceeding the available resources (ie examiners) to do the work. In this context, “new work” includes continuations, RCE’s etc, so it is these actions by applicants, rather than delay, that contribute to backlog. Having lots of claims, which increases the average amount of work associated with each application (and thus increases “service time”) also contributes. But we all knew that, and the PTO knows it, and they tried to address it by rulemaking, and we all know what happened there…

PTO strategies providing incentives to applicants to formally abandon “unwanted” applications are a good start, just as people getting fed up with waiting and leaving the bank queue is helpful for the people behind them.

But unless the total time required for an examiner to dispose of an application can be reduced (improved efficiency) and/or the number of examiners is increased, the queue will always grow once the arrival rate exceeds the steady state value.

Thank you for the article, Dennis.

“Uh, 6, he defined it the same way the PTO defines it in its PTA calculations. You guys call it “delays that show a failure “to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution.'” Dennis called it “unreasonable delay.”

In other words, nonsensically in the context of the question which Pinkus asked. The question asked was:

“Mr. Pinkos asked USPTO officials to identify the portion of the backlog that can be attributed to patent applicant delays rather than to the USPTO. ”

which information collected under that ridiculous definition doesn’t even come close to answering.

“It’s not just those logic puzzles on the LSAT that get you down, is it?”

Yes, it is. Da mn near perfect on the other sections. And it’s “logic games”, aka sequencing, sorting, matching of random nonsense etc.

With so many reasons for taking extensions, why are extensions treated so pejoratively, with name calling and nasty accusations of unreasonable delay? The PTO does not need to resort to such pejorative language: It can limit PTA for taking extensions whether they are reasonable or not. They don’t need to make me feel bad.

I like the fact that the PTO provides some incentive to avoid extensions, though, but in many clients do not understand the incentive and prefer to put off expenses as long as possible, which means that the delay is reasonable to people in the real world.

Isn’t the time between a provisional and a utility filing also applicant delay? I would be interested in what the chart would look like if we included the time between the filing of the provisional and the filing of the utility application claiming priority to the provisional.

About a year from now, it would be interesting to compare the provisional-to-utility delay and the overall applicant delay over the 12 months pre-Bilski and the 12 months post-Bilski. I would have expected the chart in this article to reflect some strategic delay to avoid rejections by holding out until the Supreme Court could loosen the Fed. Circuit’s Bilski standard — but maybe those were offset by applicants rushing to get to allowance before the Supreme Court could tighten the standard.

In essence, there is an interesting question as to whether uncertainty as to the standard for patentability impacts applicant delay. I also wonder whether Bilski impacted examiner delay.

Given the Supreme Court’s pretty extreme delay in handing down Bilski, it does seem possible that patent attorneys and even some examiners just kept waiting “one more Monday” so that they could craft their next filing to Bilski.

I hear you, Robert. The data here only indicates that 80% of the average prosecution delay past the statutory target of 36 months is attributable to the PTO. What we don’t know is how much of this is attributable to a late start on applications, such as you would expect if staffing simply isn’t keeping up with the inflow, or how much is attributable to extra non-final actions, which would suggest problems with examination. Dennis could probably tell us how many of the examinations get a late start, based on the PTA data, and what the average lateness is…

D. You are so funny. The one thing you left out of your study is the ridiculous way you defined “unreasonable delay”.

Uh, 6, he defined it the same way the PTO defines it in its PTA calculations. You guys call it “delays that show a failure “to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution.'” Dennis called it “unreasonable delay.”

It’s not just those logic puzzles on the LSAT that get you down, is it?

LOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOL

D. You are so funny. The one thing you left out of your study is the ridiculous way you defined “unreasonable delay”.

Go ahead. Define it.

“It really is as simple as that – no matter how the Office wants to spin this as an “applicant driven problem”, the real problem is squarely with the Office.”

Except, as we all know, how you define the problem determines who it is with. Attorneys sitting around and defining it in a way that it puts the blame on the office is par for the course.

Since, as you put it, Robert, “delay may not directly relate to backlog“, your question is unanswerable. At least the way you ask it.

As for accepting what you find on the internetz as “expert”, well Iza got bridge and some prime Florida land I want ya to look at.

But ya might consider that “backlog” exists because more work has come in than work has gone out. Thus “backlog” is attributable to factors affecting this delta. Process time can be one such factor and that’s what Dennis is getting at with this thread – the process is mainly in the hands of the Office. Applicant unreasonablity only accounts for a sliver of the process time.

A previous thread (and a factor here as well – see Anon’s post for a different but related aspect) has to do with what makes up that incoming swell. The fact that so many RCE’s roll in is under the direct control of applicants (6 be right on who controls the flow), but the underlying cause is the crrppy examination that the Office provides. By and large applicants are simply convinced that they have not been given a quality examination the first time around. They believe strongly enough to re-up and submit again. If examination quality were to improve, applicants would either get the patents they deserve or they would see that they don’t deserve a patent and they would abandon their efforts.

It really is as simple as that – no matter how the Office wants to spin this as an “applicant driven problem”, the real problem is squarely with the Office.

Sorry, Cy Nical, sometimes I’m not all that good at thinking for myself, but finding quick expert counsel is what the Internet is for. I’m still not sure my question has been answered, though, even given your computations, since average delay may not directly relate to backlog. What percentage of the *backlog* is attributable to applicant delay, vs. PTO delay?

Dennis,

Keep in mind that even this data is heavily skewed in the Office’s favor, because any Request for Continued Examination stops the clock and any lagging B-time is unaccounted for.

Given the impressive (?) amount of RCE’s driving the backlog, one could only imagine the true depth of unreasonable non-applicant FAIL going on.

So what conclusion can ultimately be drawn? What quantified percentage of the backlog is attributable to applicant delay, vs. PTO delay?

Come on, Robert, you can think for yourself!

Dennis says: “The 1,248 patents in my sample had an average application pendency of 46.3 months. The average unreasonable applicant delay was only 2.0 months per patent (+/– 0.2 months).”

Since the patent term adjustment statute sets a goal of 36 months. The average delay is 10.3 months. The average applicant delay is 2.0 months. So, 81% of the aveage delay is attributable to the PTO.

So what conclusion can ultimately be drawn? What quantified percentage of the backlog is attributable to applicant delay, vs. PTO delay?

This proves that almost all of the total application backlog delay is PTO delays. But what is far worse, and far more inexcusable, are the relatively few, but often much more dangerous, “submarine” patent applications [with or without multiple serial continuations] that lack of PTO supervision and laches enforcement have allowed to pend for ten or more years from their true, original, filing dates.

P.S. Now that many clients refuse to compensate O.C. for buying time extensions, the 40% who did not is not surprising, but that still leaves 60% that did?

TINLA – Yes, you are correct, 43% of the issued patents had no applicant delay beyond the usual deadlines.

Is the horizontal axis really months, as labeled, or days, as described?

Am I reading that graph crorrectly to indicate that 40% of issued patents have no applicant delay at all? In other words, in 40% of issued patents, no extensions of time were taken at all?