Guest Post by Jordan Duenckel. Jordan is a third-year law student at the University of Missouri and a registered patent agent. He has an extensive background in chemistry and food science. Before law school, he was a greenskeeper at a local golf course.

TaylorMade Golf Company teed off a dispute over golf club design and filed a patent infringement lawsuit on January 31st, 2024, in the Southern District of California against Costco and Southern California Design Company alleging infringement and false advertising relating to five of TaylorMade’s patents related to golf irons. The two defendants have not responded to the complaint but users of X, formerly Twitter, are abuzz with speculation and comments about the implications for golf at an affordable price.

TaylorMade is one of golf’s true bluebloods and releases new clubs regularly. Played by PGA Tour professionals, these clubs are not cheap with a full set of TaylorMade irons, the P790 series at issue here, running about $1400 new. Costco is more famous for membership-based bulk grocery distribution than luxury sports goods. Costco has a variety of goods that they sell in their stores as “house brand” Kirkland Signature™ products, with the 7-piece player’s irons set designed by Southern California Design Company selling for $499.99.

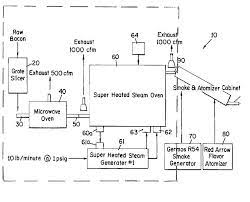

TaylorMade P790 Iron (Exploded)

Kirkland Signature™ Irons (Exploded)

For patent infringement, TaylorMade alleges infringement of five patents that contain “revolutionizing” technologies that TaylorMade asserts their patent covers. Facially, it seems the clubs look similar and may contain similar elements. Proving infringement will likely be more difficult. TaylorMade will likely attempt to find the fairway with the doctrine of equivalents. The doctrine of equivalents states that someone can infringe on a patent even if they do not literally meet all of the elements of a patent claim, as long as their product or process is equivalent to the claimed invention.

The policy rationale behind the doctrine is that patentees should be able to have appropriate coverage for their inventions even if competitors make insubstantial changes that allow them to evade the literal scope of the patent claims. If competitors could easily make small, trivial changes and avoid infringing, then patent protection would not be very meaningful.

There are three primary tests courts use to determine equivalency under this doctrine:

- The function-way-result test – The alleged equivalent product or process must perform substantially the same function, in substantially the same way, to achieve substantially the same overall result as the claimed invention. This is an objective assessment focused on comparing the major operational aspects.

- The insubstantial differences test – Courts look at whether the differences between the patented invention and the alleged equivalent are insubstantial compared to the invention as a whole. Typically only minor, trivial differences that contribute little will allow a finding of equivalence.

- The known interchangeability test – If persons reasonably skilled in the technology know that the substitute element and claimed element are interchangeable, this helps support a conclusion of equivalence.

However, there are limitations to the doctrine of equivalents. It cannot be used to effectively erase a substantive claim limitation in its entirety or vitiate a limitation. Additionally, amendments made during patent prosecution to narrow claims can estop or preclude arguments for equivalence. Finally, the prior art restricts the scope of equivalence that can be found – the alleged equivalent cannot encompass subject matter that would not have been patentable over the prior art during prosecution.

Some may question how different the clubs can be or how many ways to possibly design a golf club so the ultimate question of infringement will depend on how close Costco’s clubs come to the patent claims. Equally interesting is the false marketing claim that asserts that Costco and SCDC made false statements in advertising the Costco clubs, specifically concerning the “injected urethane insert” that is shown as the red insert on the above right photo. TaylorMade believes that both the infringement and false advertising are willful and designed to take customers from TaylorMade.

“The statement by Defendants that the accused products contain an ‘injected urethane insert’ is literally false, or in the alternative, is misleading and … has actually deceived or has a tendency to deceive consumers in a way that influences purchasing decisions. … Defendants’ false advertising has misled golf journalists and customers to believe the accused products are similar to or equivalent to the TaylorMade P790 irons.”

Redditors have been cited as an example of folks who would love to buy functionally premium clubs at a third of the price. Beyond Reddit and golf influencers, the broader public seems to be interested in the irons as Costco sold out of the irons in mere hours. Adding to the drama is the allegations that a former TaylorMade engineer helped to design the Kirkland Signature™ irons.

The irons are visually very similar, and the claim charts affixed to the complaint as Exhibits 6-10 make a compelling case for infringement by equivalent. If I were to make a prediction, I would guess that the parties settle as TaylorMade did with PXG in 2019 in a similar iron design action but only time (and maybe claim construction) will tell.