by Dennis Crouch

In recent years, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has undergone a significant shift in its examiner composition, with real implications for patent prosecution strategies.

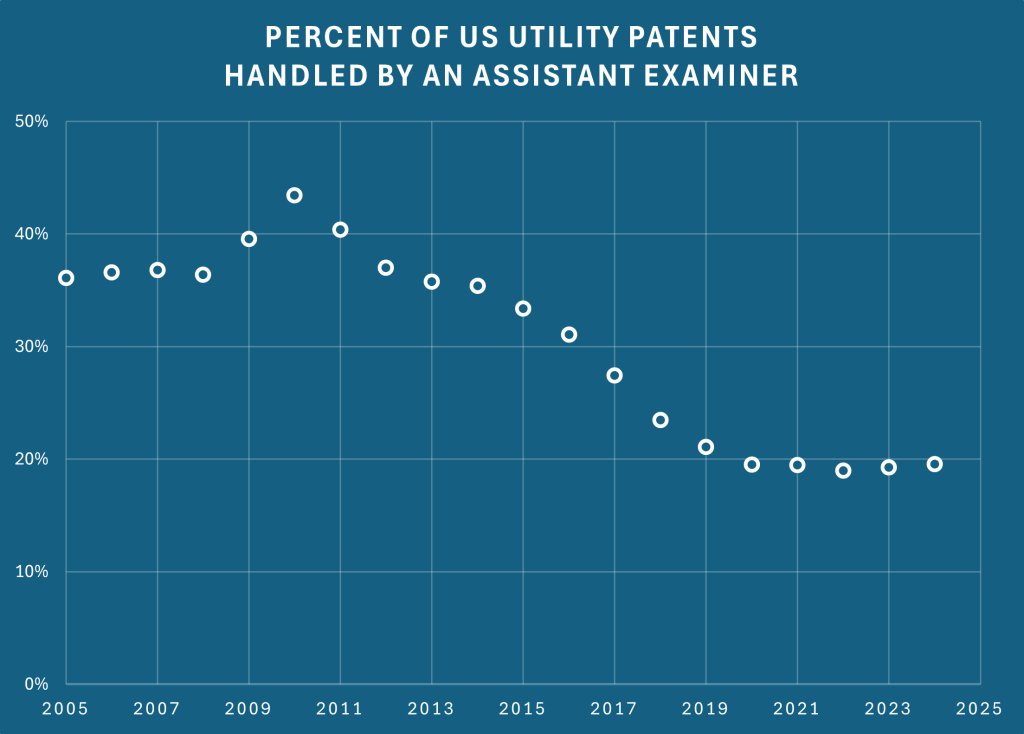

Our data reveals a dramatic drop in the percentage of assistant examiners over the past decade. Prior to 2015, over 35% of patents were examined by assistant examiners. Since 2020, this number has plummeted to less than 20%. But these assistant examiners did not simply disappear.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.