Part of the legacy of KSR will depend upon how the case is treated by the Federal Circuit (CAFC). Graham v. John Deere is the seminal patent case on obviousness, and is cited by most patent decisions involving the question of obviousness. Cases like Sakraida and Anderson's Black-Rock are much less likely to be relied-on. Sakraida, for instance, is fifty-times (50x) less likely to be cited by the CAFC than Graham -- even though Sakraida represented (until 2007) the Supreme Court's most recent pronouncement on obviousness. Sakraida's low-level influence has waned in recent times. For instance, the cow-dung case has only been cited once by the CAFC in the past decade. (in DyStar).

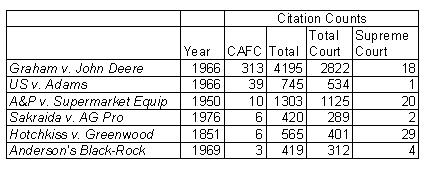

The table above shows the number of Shepard's citations found for the Supreme Court's set of obviousness decisions. Total citations include all known citations while "total court" citations include only instances where the case was cited in a court opinion. The No. 2 case (in CAFC citations) is US v. Adams. That case is notorious as the only nonobviousness case -- i.e., were the Supreme Court found the claims nonobvious.

The KSR Opinion has much more meat than Sakraida, but the case will never challenge the canonical status of Graham v. John Deere. Of course, the question of KSR's legacy is now in the hands of the CAFC.

Just an ordinary inventor

I can relate to the eureka moment. Some years ago I worked on a problem on and off for two years and then late one night, sitting in a bar with friends I zoned out, my eyes rolled back in my head, I visualized the problem and the solution. That one got me a published paper in a good journal – not too bad since I was an undergraduate at the time.

The eBay litigation makes me sick as well, not because of the treatment of the injunction remedy, which I consider a no brainer application of the appropriate principles, but because the MercExchange patent had been issued at all.

You need to be careful about what lawyers mean when they say “subjective” and “objective”. The courts will tell you the tests under Graham and KSR are both objective tests. Your concern is really focussed on the evidence rather than the test itself.

You also need to careful that you not bog down in the language – there is a danger in over intellectualizing some of these issues and falling into analysis paralysis. Look at the actual inventions being claimed in these cases whether it is eBay or KSR. If you look at the inventions you may have more sympathy for the Supreme Courts decisions.

Don’t drink too much.

Dear Joe,

Thanks you for your kind, sharing post. It is always refreshing to hear a serious scientist’s sober views. In the light of day, I’ll respond in kind.

In addition to small scale specialized manufacturing, I’ve been independently inventing since the 60’s and have a couple dozen patents covering several dozen diverse inventions, not counting things I’ve independently “re-invented” i.e., things that had already been patented. I’m not suggesting mine are, but even undeniably brilliant independent inventions happen all the time, and it is not a function of obviousness. That’s never been the issue. The relevant issue in this regard is which is the better rule, “first to file” or “first to invent.” Unlike horseshoes, close doesn’t count. The lesson to be learned is that inventing is a tough business — miss by a day, or miss by decades, there is no monetary prize for second place.

But the personal satisfaction that comes with inventing is much like obviousness — rather difficult to describe.

Anyway, as I read them, the Graham Court’s examples of factors that show “objective evidence of nonobviousness,” if anything, suggest to me the possibility that independent invention may indicate nonobviousness (but I’m admittedly partial). Those factors are: (i) commercial success; (ii) long-felt but unsolved needs; and (iii) failure of others.

To me, inventing is beautiful, and indescribably gratifying, no matter how it happens. Inventions have come to me via grueling back-breaking process, and via flash in a Eureka moment in which the invention is seen complete, crystal clear in my mind’s eye. Inventions also come in combinations of the above. Multi-part inventions are a special breed, combining two disparate ideas that no one else had seen over the course of centuries yet there it is, as clear as can be, and you wonder without end why no one else had seen it before. Some of my inventions have literally taken decades of searching and thinking about a solution for an “improvement” before the “flash” occurred.

My personal favorite came after two decades of on-off racking my brain in a particular subject area – it came to me as an image with a title in a dream. I woke before sunrise in a start with a loud burst of joy. I scared my wife so she fell out of bed. Imagine the inventor’s rush with a “flash” like that after looking so long. I’ve been blessed experiencing many means of invention.

The eBay decision made me sick. When you are an independent inventor, your patents get no respect – bigger businesses infringe without giving it a second thought. Aggressive litigation costs million$. After eBay, of course, it will be worse, because big infringers have no incentive to pay a fair royalty until after litigation, which for many inventors is prohibitive. A patent without an injunction is like a tiger without teeth.

And now KSR: I rather not get started again on this my day of R&R, except to say again that obviousness cannot be administered subjectively. A subjective obviousness test, whether wittingly or unwittingly, will lead to abuse by examiners, jurists, infringers, venture capitalists. People tend to take the easy way out, and calling something obvious just became too KSR-easy — TSM evidence is no longer required.

I think there is a tendency to equate simple with obvious, and that is a slippery slope, because, of course, everything that is simple is not obvious and vice versa, but it takes bright dedicated people to appreciate the underlying nuances. To this ordinary inventor, invention is what makes the non-obvious obvious: everything is obvious after it has been invented.

As I mentioned above, inventing is a tough business, not for the faint of heart. From a pragmatic point of view, my preferred profession, promoting progress by inventing and publishing my home-grown intellectual property, with an eye toward profit by licensing my patents, has become more perplexing and problematic as I peer into the KSR quagmire after recovering from the eBay debacle, and I am psst.

I’ll offer my favorite story as a peace offering. A little kid announced to his teacher that he found a dead frog on his way to school. She asked, “How do you know the frog was dead?” The little guy answered, “Because I pissed in his ear and he didn’t move.” Taken aback, but rather amused by the response, the teacher said, “Well, just how did you go about doing that?” The little kid responded, “You know, I leaned down real close to his ear and said, “Psst.”

Hey, its that time again…

“I’ll bet we’d get along great over drinks.”

If you talk the way you write there would probably be a breach of the peace.

“I, obviously, from an inventor’s view. What’s your angle?, or, rather, agenda?”

My background is technical – Physics, math, computer science, economics. I have made my living in applied research and as a computer programmer, among other things. I may be closer by training and temperament to inventors than I am to patent lawyers. I know from personal experience that in many areas of endeavor, where there is no prospect of a patent, there is still robust progress.

My interest is the economics of property rights. Well designed property rights systems are at the core of Western freedom and prosperity. Inappropriate property rights systems will hold us back. When I look at examples of patents like Verizon or Forgent or Eolas or NTP or Teleflex or MercExchange I come away thinking that there is something profoundly wrong with the current patent system.

Hope you’re not too hungover.

Dear Mr. Smith,

I am not familiar with the Verizon patent you characterized.

However, with all due respect, your comments leading up to that patent’s characterization either are (a) in direct conflict with central patent doctrine or (b) ought to be understood without saying (pardon me for saying so but your saying so evidences a lack of understanding).

Please take the opportunity to re-think and retract your shallow and dangerously misleading comments. Bear in mind, if you cannot come up with a useful answer to the question of the day,

“HOW WOULD YOU TEST FOR OBVIOUSNESS?,”

you are allowed to just and say so. Please don’t be embarrassed. Even the Supremes added nothing useful to the Catch 22 Obviousness quandary; to the contrary, what they accomplish was to thicken the Obviousness quagmire with sticky subjectiveness.

For clarification, after so many opined all week to and fro about the Supremes’ long-awaited KSR opinion, may I say,

TEACHING, SUGGESTION, MOTIVATION works because TSM is not subjective. QED.

PS1: Joe, I’ll offer a bit of advice:

Please google “Strange Loop” and “flash of genius.”

Check out: link to www2.merriam-webster.com

(I didn’t invent “gradual betterment”, perhaps Noah did).

PS2:

My opinions are that

(i) LICENSING IS PREFERRABLE TO INFRINGING,

and that

(ii) TEACHING, SUGGESTION, MOTIVATION works because TSM is not subjective..

PS3:

Also bear in mind it is Saturday night after refreshment, and, truly, I mean no disrespect. I’ll bet we’d get along great over drinks. It is obvious to me that we both strive to be proud patent people, I, obviously, from an inventor’s view. What’s your angle?, or, rather, agenda?

These comments give me the chance to make the link between KSR, Leibel and the Wright Brothers. The only reason for a Govt to grant a 20 year monopoly is to Promote the Progress. For Applicants to get 20 year monopolies on obvious (ob via = lying in the road) doesn’t promote, it hinders (such patents are blocking the ordinary man’s way forward). Conversely, 20 years on a non-obvious contribution stimulates 1) investment in innovation and 2) efforts to design around. You can’t paraphrase “obvious”. Obvious is obvious. You shouldn’t give a person 20 years of exclusivity for defining an obvious desideratum, such as “Heavier than air flying machine” or “Telephone using the internet”. In England we call such things “Free Beer” claims: a claim to a desirable objective, obvious in itself, but not obvious how to provide. Instead, you give the monopoly not for defining the problem but for defining and enabling the invented solution, and require that the claim be enabled over its full reach. It is banal to cry that there are always non-functional embodiments within the scope of such a claim, and banal to answer it with the point that the reader of the claim has to be credited with a mindset of wanting to follow the enabling disclosure actually to build something that works. That’s the EPO’s “Principle of Synthetical Propensity”. Sometimes one really has the feeling that the CAFC, and the clerk for Kennedy LJ, are finding European patent jurisprudence helpful.

“just an ordinary inventor” argues that the publication is the primary means by which patents promote progress. I do not believe this and doubt there is any empirical evidence supporting it. I expect, although I cannot prove, that to the extent patents promote progress they do it primarily through protecting investments in research and development.

“just an ordinary inventor” suggests that progress is too fast and that it might be a good thing if patents slow it down. Progress is not as fast as people believe and is certainly not as fast as I would like. That said, if the current patent system is a drag on progress then it is unconstitutional.

So far as a test – I am generally happy with the language in Graham v. John Deere and in KSR. The word “obvious” does not appear in the constitution and may not be the best word for the concept which Congress and the courts were seeking to capture: namely, that patents should not be granted on inventions which were inevitable and needed no incentive. “Obvious” is the word we are stuck with for the time being and all that the courts can do with it is to interpret it in a manner consistent with the Constitution if they can and strike it down if they can’t.

I believe that there are three types of evidence which should be considered in determinations of obviousness which I don’t recall seeing in the cases: (1) if the invention is one which as soon as it is conceived is known to work – that is that there is no need to build prototypes or do experiments that will tend to demonstrate obviousnes; (2) independent invention is strong evidence (but not proof) of obviousness; (3) the need to do expensive research, testing or prototyping before arriving at the design which is being patented should be evidence (but not proof) of non-obviousness.

A patent like the Verizon patent which effectively says:

1. we claim a patent on the idea of interconnecting the internet and the telephone system for voice communication;

2. we claim a patent on the use of standard system design elements in the course of implement claim #1

should not be permitted. There is no research needed to get the idea to that stage and you know as soon as you write it on a piece of paper that it can be made to work from a technical point of view even if you do not know if it will be commercially viable.

The Verizon patent does not seem to be alone in this combination of a claim to a straghtforward idea combined with claims for the then obvious methods of implementing that idea: the Eolas and the NTP patents both seem to follow the same format.

a british case to muddy the waters:

link to publications.parliament.uk

Does the ruling state any changes to the non-publication time frame currently in use by the PTO?

Re: “The bar for patents had been set too low and was past due to be raised.”

Mr. Smith, you miss the salient point of patents. Yes, to promote progress is the purpose of patents, of course, that is the goal. You must bear foremost in mind, however, that:

The means to accomplish this goal is to encourage inventors to publish their work.

It is obvious to even the most casual observer that a lower bar encourages more publishing that a higher bar. QED.

Postscript: Those who would put a patent to use can license it or infringe it (and hopefully trebly pay the consequences). Or they can wait till the patent expires. One could argue that technology moves too fast anyway.

Be that as it may, by definition progress is “gradual betterment; especially : the progressive development of mankind” (emphasis on “gradual”).

So, if you don’t want to license or risk infringing, be patient and let the clock run out. Also, with all due respect, Joe, your attempted characterization of my commentary on obviousness missed the mark — you didn’t get it.

Try this: How would you test for obviousness? Despite hundreds of KSR comments, I’ve seen damn few new and useful ideas about that.

“just an ordinary inventor” wallows in existential angst over the meaning of obviousness and then argues that since the question of obviousness might be hard that anything new which has not already been expressly anticipated in writing should be patentable.

The goal here is not the administrative ease of the PTO, or the comfort of the CAFC. The goal is to have a patent system which promotes the progress of the useful arts. The Supreme Court is alive to the issue which an inward looking patent industry (or at least 80% of the people who post to this blog) wants to ignore: “Granting patent protection to advances that would occur in the ordinary course without real innovation retards progress”

The bar for patents had been set too low and was past due to be raised.

“Past 101” dammit.

The SC used predictable a lot and I generally think it’s a good thing. Yes, I am concerned like all of you about hindsight reconstruction and I am even more concerned about Examiners interpreting this a carte blanche to make any wacky combination rejection they want. But I cannot believe the chicken little reactions I am seeing on this board

The SC has a point about the CAFC’s rigid application of TSM and do any of you disagree that it needed to be modified. I, myself, have been saying to colleagues and clients for years that if I could overcome the 102 rejections, overcoming a 103 was almost a given because of TSM. It’s made obviousness a joke.

I think predictability is a good standard. If I have Element A and Element B and anyone skilled in the art could predict what would happen when you combine A and B then how is that not obvious? Essentially if you gave the same problem to a class of engineers, how many would give you back the same answer.

If it is true that the result of the combination is predictable only in hindsight shouldn’t it be relatively easy to show that the result prior to invention was either unpredictable or expected to be different?

I work in the electromechanical and software arts and I don’t really see this as that important a case (Unlike say Flarsheim – now that is a scary opinion)

You can’t patent theoretical concepts like relativity, quantum theory, or brownian motion. These exist regardless of whether someone thought of them (assuming we live in an objective universe – don’t want to stray from the physical to the philosophical, but just clarifying). Einstein’s theories would never have to face an obviousness standard as they would never make it pass 101.

Einstein’s Theory: Here’s a thought, logical thinking, may be even obvious thinking:

When an object emits something it must become lighter. It follows that, when a flashlight emits light, it becomes lighter.

Lighter means, e.g., a decrease in mass.

The decrease would be equal to the amount of light energy radiated divided by the square of the speed of light (because the time tested and long-known rule is that light diminishes proportional to the square of the distance from the source).

Laws governing the conservation of mass and the conservation of energy are also time-tested and have been known for a long time.

Therefore, I ask, was the following obvious to “one skilled in the art”?:

“When an object emits light, say, a flashlight, it gets lighter.”

A. logical, even obvious;

B. in Einstein’s day, physicists knew that mass and energy were interrelated; and

C. they knew that the brightness of light c decreased by the square c2 of the distance from the light source.

D. Was m = E/c2 (same as E = mc2) therefore obvious to skilled-in-the-art physicists after it was formulated? I suspect a physicist upon seeing the formula for the first time might have slapped his forehead and said, of course!, why didn’t I think of that!

Here is a fascinating audio link that motivated the question above: link to pbs.org

Here is the absurd hypothetical imponderable – would the Supremes have rejected Einstein’s discovery as obvious? Hey, you never know.

Thanks for the invite.

Some early morning repetitive ramblings from an inventor type, which seem to capture the moment. After all, “Obviousness” is an abstract abstraction, isn’t it?

IS MEASURING OBVIOUSNESS LIKE MEASURING A CLOUD?

How are “creativity” and “obviousness” related?

What does “ordinary skill in the art” (without more) have to do with creativity?

Are “inventiveness” and “creativity” closely linked?

Is creativity more of a “process”?, and does inventiveness comes on like a “flash” out of nowhere?, a “Eureka!” moment? Personally, I become almost intoxicated with joy and excitement when I have a pragmatic inventive flash. Some of my inventions came from a “process” and others from a “flash.”

Whether a “process” or a “flash,” if one could devise a test to measure a person’s latent creativity level, I wonder if it would relate to testing for obviousness?

Be that as it may, I’ve encountered some highly educated skilled in the art people that can’t create themselves out of a paper bag. This gives rise to the essential patentability question: Does ordinary skill in the art mean: (i) a creative person skilled in the art?, or (ii) merely an educated person skilled in the art?

If the answer is the former (i) then, potentially, nothing would ever be patentable — and a lot would depend on the level of creativeness required, and you’d be out of the pan into the fire, because, how do you measure creativeness?

And if you did have experts devise a test for creativeness, to whom do you administer the test?: The inventor, the examiner, Justices, appellate Judges or the Supremes, Congress or the elected Executive Branch officials, maybe the jurors, an infringer or the man on the street, those skilled in the art … just who?

What bearing does the perception of an invention being “complex” or “simple” have? Everything that is simple is not obvious and vice versa. No one suggested simple and obvious were the same, but neither this general subject matter nor any similar notion, which you’d think would of course be an integral part of any serious discussion of obviousness, seems to come up.

What is invention? Invention is what makes the non-obvious obvious: everything is obvious after it has been invented. Another problem when testing for obviousness for patentability has to do with the Observer Effect, defined as: “In science, the observer effect refers to changes that the act of observing has on the phenomenon being observed.”

I.e., Before and after observation: before observation, is, is what it is, but after observation, what was no longer is – before’s is is gone forever after observation.

It is, of course, impossible to tell if an invention is obvious before it has been invented – it has not yet been discovered, and thus it does not (yet) exist. And after it has been invented, at least to the extent that invention is what makes the non-obvious obvious, you can no longer tell if an invention was obvious.

After its inception, the CAFC had devised a pragmatic obviousness test, “Teaching, Suggestion, Motivation,” or TSM, a test that is determined by the presence of some real evidence, or the lack of evidence. Of course, there will be raccoon-like on-the-fence cases, and some silly stuff may slip through, but that’s life, and that’s what court’s are for.

Teaching, Suggestion & Motivation worked because TMS is based on identifiable evidence – patentability cannot be likened to a cloud.

These predictions THAT WERE OBVIOUS TO THOSE MOST SKILLED/EDUCATED IN THEIR RESPECTIVE ART seem to highlight the difficulty & absurdity, nay the futility, in measuring obviousness without something tangible, like Teaching, Suggestion & Motivation, TSM:

“Everything that can be invented has been invented.” — Charles H. Duell, Commissioner, US Office of Patents, 1899.

“Man will never reach the moon regardless of all future scientific advances.” — Dr. Lee DeForest, “Father of Radio & Grandfather of Television.”

“The bomb will never go off. I speak as an expert in explosives.” — Admiral William Leahy, US Atomic Bomb Project.

“There is no likelihood man can ever tap the power of the atom.” — Robert Millikan, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1923.

“Computers in the future may weigh no more than 1.5 tons.” — Popular Mechanics, forecasting the relentless march of science, 1949.

“I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.” — Thomas Watson, chairman of IBM, 1943.

“I have traveled the length and breadth of this country and talked with the best people, and I can assure you that data processing is a fad that won’t last out the year.” — The editor in charge of business books for Prentice Hall, 1957.

“But what is it good for?” — Engineer at the Advanced Computing Systems Division of IBM, 1968, commenting on the microchip.

“640K ought to be enough for anybody.” — Bill Gates, 1981

“This ‘telephone’ has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication. The device is inherently of no value to us,” — Western Union internal memo, 1876.

“The wireless music box has no imaginable commercial value. Who would pay for a message sent to nobody in particular?” — David Sarnoff’s associates in response to his urgings for investment in the radio in the 1920s.

“The concept is interesting and well-formed, but in order to earn better than a ‘C,’ the idea must be feasible,” — A Yale University management professor in response to Fred Smith’s paper proposing reliable overnight delivery service. (Smith went on to found Federal Express Corp.)

“I’m just glad it’ll be Clark Gable who’s falling on his face and not Gary Cooper,” — Gary Cooper on his decision not to take the leading role in “Gone With The Wind.”

“A cookie store is a bad idea. Besides, the market research reports say America likes crispy cookies, not soft and chewy cookies like you make,” — Response to Debbi Fields’ idea of starting Mrs. Fields’ Cookies.

“We don’t like their sound, and guitar music is on the way out,” — Decca Recording Co. rejecting the Beatles, 1962.

“Heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible,” — Lord Kelvin, president, Royal Society, 1895.

“If I had thought about it, I wouldn’t have done the experiment. The literature was full of examples that said you can’t do this,” – – Spencer Silver on the work that led to the unique adhesives for 3-M “Post-It” Notepads.

“Drill for oil? You mean drill into the ground to try and find oil? You’re crazy,” — Drillers who Edwin L. Drake tried to enlist to his project to drill for oil in 1859.

“Stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” — Irving Fisher, Professor of Economics, Yale University, 1929.

“Airplanes are interesting toys but of no military value,” — Marechal Ferdinand Foch, Professor of Strategy, Ecole Superieure de Guerre, France.

“The super computer is technologically impossible. It would take all of the water that flows over Niagara Falls to cool the heat generated by the number of vacuum tubes required.” — Professor of Electrical Engineering, New York University.

“I don’t know what use any one could find for a machine that would make copies of documents. It certainly couldn’t be a feasible business by itself.” — the head of IBM, refusing to back the idea, forcing the inventor to found Xerox.

“Louis Pasteur’s theory of germs is ridiculous fiction.” — Pierre Pachet, Professor of Physiology at Toulouse, 1872.

“The abdomen, the chest, and the brain will forever be shut from the intrusion of the wise and humane surgeon,” — Sir John Eric Ericksen, British surgeon, appointed Surgeon-Extraordinary to Queen Victoria 1873.

And last but not least…

“There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home.” — Ken Olson, president, chairman and founder of Digital Equipment Corp., 1977.

So much for the “Wise Minds”…..

Small Inventor — I was mucking around with the server and unfortunately deleted the comments. Perhaps the anonymous poster can go-again.

There were two excellent comments here directly related to the subject of discussion on obviousness…

Could those comments be restored ?

As of this moment the blog article indicates that three comments have been made. However, only what is presumably to third comment appears.

Is there perhaps a glitch?

“The question of KSR’s legacy is now in the hands of the CAFC.” Good point. Let’s hope the CAFC twists it back into the right direction.

On a different note, is there a way for you to set up a thread to report and characterize incidents of when a patent examiner cites KSR v. Teleflex in their Office Action?