A large portion of PTO revenue comes through applicant’s payment of maintenance fees. Under the current fee structure, three post-grant maintenance fees must be paid in order to keep a patent from prematurely expiring. A large entity pays $980 3.5 years after issuance; $2,480 7.5 years after issuance; and $4,110 11.5 after issuance. If the fee is not paid then the patent will expire at the next 4, 8, or 12 year mark. In FY08, the PTO reported over $500 million in revenue from maintenance fees.

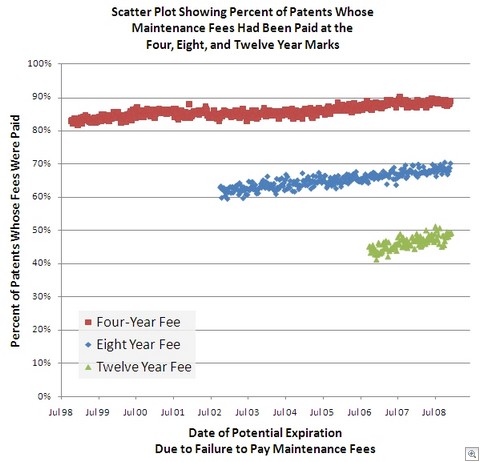

I wanted to look at how maintenance fees are being paid, so I downloaded the past decade of OG Notices and parsed-out notices of patent expiration. The chart below shows some results.

The chart shows survival rates for the four (red), eight (blue), and twelve (green) year marks. Each datapoint represents the average survival rate for patents that would have expired on that date. For instance, of the 2229 utility patents that issued on December 31, 1996, the first fee was paid for 84% of the patents, the first two fees were paid for 63% of the patents, and all three fees were paied for 49% of the patents. (Note – I did not yet add-back cases that were revived due to unintentional abandonment.)

The median patent has an ordinary enforceable term of about 17 years. This is based on the twenty year term which begins at filing of the non-provisional application minus three years of prosecution. If prosecution takes longer than three years, then the term will likely be extended under the PTA provisions.

However, this data shows that the median patent term is actually cut short by about five years because applicants decide not to pay the large final fee.

A third feature to recognize from this chart is that the percentage of patents whose fees are being paid is increasing over time. However, the PTO has indicated that it expects a drop in maintenance fee payments due to the economic slump.

Judge Moore looked at expiration data for patents issued in 1991 in her paper on “Worthless Patents.” Her result is that patents were more likely to “survive” (i.e., have their maintenance fees paid) when they have more claims, more art cited, more related applications, and longer prosecution times. US corporate owners were more likely to pay the fees than individual or foreign owners. She also found that Semiconductor and Optics patents were the most likely to survive. Amusement patents were unlikely to survive.

I look forward to your further study of unintentionally abandoned cases. Will you also have data on cases where the maintenance fees were paid late? I’m particularly interested as this may add a tracking/convenience/budgeting argument to other arguments for revision of fees to a more “front-ended” system which can relate fees to examiner work performed during prosecution. Most other countries have an annuity system which includes on-going payment during the examining phase or accumulated anniuties upon grant. The EPC is also, in April, moving specification costs up from grant to EP filing/entry from PCT. With a further nod to Europe, one does not take lightly the filing of a Divisional in Europe given the financial burden, including accumulated annuity fee payments. A similar model in the US could also alleviate the backlog and perceived divisional/continuation abuse. Of course, small (or micro) entity status can be used to limit the up-front financial impact to SMEs and individual inventors.

Further to my note above, a major foreign company notes that its 11.5 year U.S. maintenance statistics closely track those found by Dennis. However, they also note that [for cost/time effort reasons] they only conduct a maintenance review once for each patent, only at ten years after issuance. Thus, of course, they unfortunately miss any potential cost savings in avoiding any 4.5 and 7.5 year maintenance fees. I am sure they are not the only ones making such cost-effectiveness trade-off decisions.

BTW, some of the academic publications of economists cum patent experts are apparently unaware of the fact that their reported scare numbers of “increasing numbers of patents in force” are way off the mark by miss-counting all these completely lapsed patents as if they were still in force.

If the USPTO needs money they should just allow every application pending right now, especially the short ones because they are easier to print, and start collecting issue fees. That’s the fastest way to generate revenue, plus it’ll make their customers happy. Why is this is so hard?

/Church of Bobby Jindal off

Boundy: “Maybe the PTO should give a little more credit to the observations and predictions of those of us in the private sector that have to be accountable for the economic consequences of our decisions..”

LOLOLOLOLOLOLOL.

Boundy’s a wingnut, too? Oh spare me.

Maggie H, and others, you are assuming consistent and logical reasons for paying or not paying maintenance fees. But corporate patent department budgets and their variations, and higher level management whims or changes, can also play major roles. Also, the time and effort in making large numbers of well-considered non-maintenance (patent lapse)decisions is not a trivial cost. [Perhaps it could also be more objectively out-sourced in some cases?]

“the economic consequences of our decisions”

Well put Mr. Boundy, and in sharp contrast, to the outgoing management that thought it was a good idea to spend a lot of money on hiring someone to come up with the “new rules,” trying to shove them down an unwilling patent bar’s throat despite an overwhelmingly negative response, and then to have the audacity to file a baseless appeal of the decision that ultimately and soundly repudiated those rules without regard to any economic consequences.

Only in government can you get away with such wanton and reckless disregard for the bottom line.

The purpose behind the elimination of the 103 motivation to combine was to keep seemingly simple inventions from becoming patented. However, there never was any showing of the horrors of having patents on seemingly simple inventions. The above chart (and a more focused analysis) would seem to show that many patents for seemingly simple inventions expire when the eight year fee comes due. Dennis, perhaps you can do a study addressing this.

Ocean Tomo’s Patent Ratings system works on the basis of maintenance rates. I believe the core principle with their ratings system is that the person/company with the reins on the maintenance fee payments is best positioned to determine whether the patent is worth the $ to maintain at the various MF points. Thus, if patent A has been maintained longer than patent B, patent A is likely to hold more value for its owner. Using statistical models, they have aggregated a huge amount of the USPTO patent and MF data, and found a statistically significant correlation between maintenance rates (ie value according to their proposition) and certain characteristics of the patents (# claims, # words and 100 or so others). So, they can take any given patent and give it a rating in their sea of data compared to other patents. The Ocean Tomo auctions make use of these ratings in the marketing material. If you’re looking for prior research of any sort, I am sure PatentRatings would have some.

are you saying that if the fourth year maintenance fee is not paid the patent will not expire until the eighth year fee comes around?

It was interesting to hear Mr. Doll concede at the Deferred Examination Roundtable that the PTO is hurting for maintenance fees because of lower allowance rates and higher rework (which, as any attorney and the PTO’s own statistics will tell you, is overwhelmingly caused by the sharp drop in the quality and care of rejections, not any change in applications – look at the plummeting rates of affirmance on appeal! Under 10%! See link to works.bepress.com slide 15, in combination with link to uspto.gov).

I second the observation of Judge Moore and hp684 that the very patents that the PTO believes are too “big” and “complex” to examine are exactly the patents that are most valuable, and that protect the biggest concept-to-product investments. We noted that in a letter to OMB during the White House review of the Continuations/Claims rule:

link to whitehouse.gov

Maybe the PTO should give a little more credit to the observations and predictions of those of us in the private sector that have to be accountable for the economic consequences of our decisions…

For those “high patenting companies”, those with 1000+ patents a year every year, I am wondering how many patents they maintain. Would it be a greater fallout because they patent everything whether of commercial value or not, or would it be a lesser fallout because they go to the bother to invest in patenting everything with the corresponding vast supporting systems?

1. Sorry, there is no “license of right” system in the U.S. [unlike European countries] to significantly reduce patent maintenance fees in exchange for agreeing to a [rarely requested] license. But at least in the U.S. we don’t have the hassle and cost of annual maintenance fees for applications pending for years before even becoming patents [if ever] in the EPO, etc.

2. Dan, excellent point that there is no longer any direct correlation [or logical relation] between patent maintenance fee dates and the remaining terms of many patents due to application processing delays.

“when they have more claims, more art cited, more related applications, and longer prosecution times” — these are the patents which are more likely to have at least some of their claims maintained during litigation.

That may be true for the first two factors, but I’d say that the correlation between prosecution time and payment of maintenance fees has a different reason: if the patent owner has gone through the hassle of a long prosecution, it’s presumably because he believes that the patent is valuable, and he’s hardly going to abandon it at the first maintenance fee. A vanity patent is much more likely to be abandoned at the first prosecution hurdle. Patents who’ve gone through a “difficult birth”, on the other hand, are much more likely to be both valuable and borderline…which, incidentally, will bring them so much more often to litigation.

Likewise, a large number of related patents reveals an aggressive, organised strategy on the part of the patent owner, not necessarily that the individual patents are more solid or valuable. Such a patent owner is simply unlikely to abandon his patents early.

this data shows definitively that all those “bad” patents (according to the USPTO policy, all patents) are too “big” in the economic sense, to be allowed to become invalid.

every time they make it easier to declare innovations “obvious”… less patents are filed/retained, USPTO fee income drops.

so it is the patent office that is ruining its own budget/driving our economy into the toilet.

put that in your pipe and smoke it, USPTO.

Sorry, what I meant was

Does US patent law provides for “License of Right” provision, whereby and upon making an entry to that effect with the patent office you pay but only half of the amount per annuity to the office. If yes, how well is this option used? Appears that though this provision exists in certain jurisdictions but it remains in dark, relatively unknown and unpublicised.

Is there anything like “License of Rights” in the US, whereby you pay half of the annuities. If yes, how well is this option used?

“when they have more claims, more art cited, more related applications, and longer prosecution times” — these are the patents which are more likely to have at least some of their claims maintained during litigation.

my guess is that the recession will reduce the amount of maintenance fees paid by about a third

Dennis, one anomoly you didn’t discuss, and that should probably be taken into account when analyzing the data, is the fact that when the US moved to 20 years from earliest filing, it kept in place the maintenance fee schedule that was based on the old 17 years from grant system. This means that in the US it’s now possible to get a patent where there’s no opportunity to pay the 12 year fee (or in some cases even the 8 year fee) b/c the patent may issue more than 8 or even 12 years after the earliest filing date and no patent term extension is available. For example, if the patentee only filed the divisional application at the same time it paid the issue fee in the parent case, and prosecution of the parent took 5 years and prosecution of the divisional took 4 years. This would tend to skew the data toward more payments of the 4-year and 8-year fees.

Thanks for your independently researched data.

In 3/28/03 I received the following PTO email response to my question on this very same subject:

“Fiscal Year 2002 statistics show that 38.4% of third stage maintenance fees due are paid. Second stage is 59.5%.”