by Dennis Crouch

The USPTO is struggling somewhat with how to implement preissuance submissions.

Required Concise Description: The new provision created by the America Invents Act (AIA) opens the door for any third party to submit “any … printed publication potential relevance to the examination of the application” if submitted within the proper window following application publication. 35 U.S.C. 122(e)(1). The preissuance submission must also include a “concise description of the asserted relevance of each submitted document.” 35 U.S.C. 122(e)(2)(A).

The senior managers at USPTO learned patent law in the days when patent prosecution was extremely ex parte. Before 2001, pending applications were not published and were instead kept in complete confidence within the USPTO. File wrappers were only reviewed in paper copy form and patent law was not generally thought of as much of a public concern. Those days are gone, but fragments of that history remain.

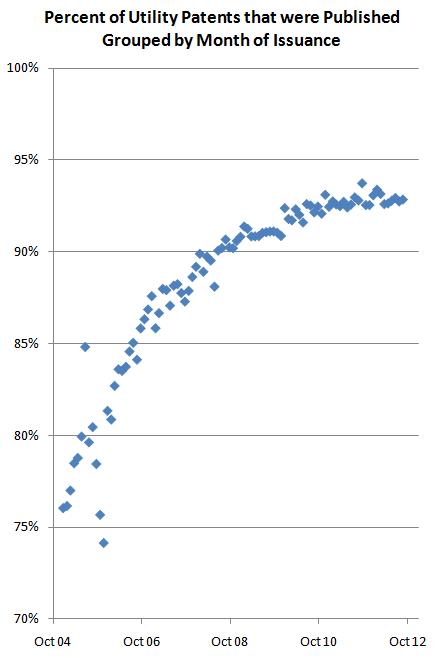

In 1999 the omnibus appropriations bill included American Inventors Protection Act of 1999. The AIPA implemented a new program of publishing pending patent applications 18–months after filing. Applicants still have the option of keeping their applications secret while pending. However, that option requires that the applicant forego non-US patent rights. As the chart shows below, the vast majority of applications are published prior to issuance. Further, about half of the non-published applications are ones that issued within 18 months of filing.

The new publication system raised a concern that third parties would begin challenging patents before issuance. As part of the legislative compromise, the 1999 AIPA legislation also included a special provision that blocks preissuance protests and oppositions. The provision authorizes the USPTO Director to establish procedures to ensure that no pre-issuance opposition is initiated following publication.

Protest and Pre-Issuance Opposition.— The Director shall establish appropriate procedures to ensure that no protest or other form of pre-issuance opposition to the grant of a patent on an application may be initiated after publication of the application without the express written consent of the applicant.

35 U.S.C. 122(c). The USPTO recognizes that the new preissuance submission system is in tension with the rule against allowing pre-issuance oppositions. In its implementation regulations the USPTO attempts to provide some limitation on the submissions in order to avoid the conflict. In the explanation of the final rules, the USPTO writes:

The third party should present the concise description in a format that would best explain to the examiner the relevance of the accompanying document, such as in a narrative description or a claim chart. The statutory requirement for a concise description of relevance should not be interpreted as permitting a third party to participate in the prosecution of an application, as 35 U.S.C. 122(c) prohibits the initiation of a protest or other form of pre-issuance opposition for published applications without the consent of the applicant. Therefore, while a concise description of relevance may include claim charts (i.e., mapping various portions of a submitted document to different claim elements), the concise description of relevance is not an invitation to a third party to propose rejections of the claims or set forth arguments relating to an Office action in the application or to an applicant’s reply to an Office action in the application.

PreIssuance Final Rules (July 2012). In its discussion of the new rules, the USPTO also suggested that the concise description is “limited to a description of a document’s relevance” cannot include “arguments against patentability.”

Unlike the concise description of relevance required by 35 U.S.C. 122(e) for a preissuance submission, which is limited to a description of a document’s relevance, the concise explanation for a protest under 37 CFR 1.291 allows for arguments against patentability.

Clearly there is a limit here to the scope of the description that can be filed. However, the USPTO’s distinction between a description and explanation is not entirely clear.

The USPTO’s approach here makes some sense but is somewhat misguided. In my mind, the statutory mandated description of relevance seems to requires at least some indication the statutory hook. This is especially true because the preissuance submissions are not limited to 102/103 related prior art submissions. Rather, the submissions merely need to be potentially relevant to examination. The best interpretation of the statute is that the discription of relevance is a description of how the submitted document is relevant to the examination. In my mind, this sets up a three way network and the required description should discuss how (1) the submitted document changes how we think about (2) the patent application based upon some (3) law or other element of patent examination. In the context of a claim construction chart, the link to 102/103 will likely be implicitly understandable without discussing the statutory elements. Explanations regarding claim construction, subject matter eligibility, indefiniteness, or other examination issues likely will not make sense unless at least those particular labels are provided in the explnation of how the document is relevant to the examination.

Although I do not believe the application must be published in order for someone to submit information, the issue is largely irrelevant. If the application has not been published yet by the USPTO, then the information can be submitted as a “protest” under 37 cfr 1.291. This was the same under the prior rules as well.

Thanks Ned, for your report on your “one case” at the EPO. But those observations at the EPO did the observer more harm than good didn’t they? What adverse effect did they, on your client? What have you to fear, from such futile observations? What makes you think that the tenor of such observations will ever happen again? Why do you think your experience is anything other than an aberration? How does that invalidate the public policy objective of Art 115 EPC?

Ned, I agree completely. However, there are at least two postings on this blog that say the application must be published, and no one seems to have stepped up to argue the contrary position based on either the statute or rule.

Max, in one case, the observations were not so much a discussion about prior art as a commentary on my client, his motives, and his alleged agendas.

Recall, i4i v. Microsoft. MS was sanctioned for litigation misconduct for similar antics in court. But there it happened in to us in the EPO.

“It’s already been done. The mere submission of information relevant to patentability is not an “opposition” or a “protest” or a “form of opposition.” Such submissions were allowed under Rule 99. ”

Lets see how long it takes you to realize how self-defeating this statement is.

you are famous for your “whatever” view of law

This “view” applies only to one or two very narrowly described circumstances which you and your sockpuppets either (1) failed to understand or (2) pretended not to understand.

More accurately, is you anon

(and your sockpuppets) who are “famous” for not understanding why claims in the form [oldstep]

+[newthought] must be either ineligible under 101, anticipated per se under 102 (as proposed by the government) or unenforceable. The reason underlying this conclusion is identical and the analysis is virtually indistinguishable. That’s why it does not really matter how you get to the end result (a worthless piece of paper) unless (as was pointed out before during and after the Prometheus decision by me and at least one Supreme Court Justice) one is concerned about creating the new doctrine that allows Examiners ignore mental steps when examining claims for anticipation.

if you want to advance a position that 35 USC 122 does not apply, then the onus is on you to support that view

It’s already been done. The mere submission of information relevant to patentability is not an “opposition” or a “protest” or a “form of opposition.” Such submissions were allowed under Rule 99. As I wrote, it’s no more an “opposition” than telling the weatherman to stick his head out the window before describing the weather. And it doesn’t become more of an “opposition” if I tell the weatherman concisely why he should stick his head out the window.

“Yes, that’s the point of the exercise.”

Respectfully, you miss the point. The point of the thread (and the real issue at heart here) is that it really does matter as to how you reach that point of the exercise.

I realize tht you are famous for your “whatever” view of law (that is, until the law reaches your own backyard), but “whatever” does not fly, and the Office must obey the law as it stands.

Now if you want to advance a position that 35 USC 122 does not apply, then the onus is on you to support that view. I would say “I believe your opinion in that regard is difficult to support in light of the facts presented here” but there have been no facts presented here to support that opinion – only calls for me to provide Supreme Court citations for something I need not do.

So while “the point of the exercise” may be noble and righteous, it really does matter very much the route taken in getting there – the ends really do not justify the means.

[Why would the U.S. want to prevent citizens from obtaining foreign patents, in this situation?]

Do you find the US is trying to prevent citizens from obtaining foreign patents? What situation is this happening in, in your experience?

Oh Ned, what a tease you are. Of your Art 115 EPC experience at the EPO you report:

“…we do not want to have that in the US. Not at all.”

but you don’t say WHY. Can’t you give me just the merest smidgeon of a hint? Or would that be too dangerous because it might encourage others to file observations on patentability.

I’m curious, you see. Most folks in Europe positively decide NOT to file observations at the EPO pre-issue. Better to keep your powder dry, and then oppose the issued patent. So how come your client, the EPO Applicant, was disadvantaged by the pre-issue observations from that tiresome member of the public? Most attorneys handling prosecution at the EPO would have kissed the observer and said thank you very much, but not you Ned. Why?

I’m all eyes.

Assume Applicant notifies the USPTO to rescind the non-publication, either a) before the foreign filings; or b) <45 days after the foreign filings.

Again, assume the foreign filings do not have a priority claim to the earlier USPTO application.

[Why would the U.S. want to prevent citizens from obtaining foreign patents, in this situation?]

Thanks. Others may comment too.

the applicant may simply cancel or amend clearly invalid claims.

Yes, that’s the point of the exercise.

Larry, regardless of the rule, the statute seems to suggest that a 122(e) submission may be made at any prior to the limits specified regardless of publication.

I’d like to add, that I have experienced third party observations in the EPO and in Japan. Having had that experience, I can assure you that we do not want to have that in the US. Not at all.

Back in the day, I may have been the source of the limitation on protests, oppositions and public use proceedings when I raised the issue with the PTO when we were discussing publication of patents. Obviously, the do-gooders of the world believe they have a better plan than mine. What we may get is what we now have in Europe or in Japan. Very unfortunate. Very.

Malcolm, the issue really is to keep the opinion/commentary of the third party away from the examiner.

MM, there is no duty to disclose the opinions of third parties to the examiner. The reference itself may be cumulative. Regardless, the applicant may simply cancel or amend clearly invalid claims.

Similar procedures were available under Rule 99. Find a reference. Anonymously publish a “review” of the reference online, highlighting key features of the reference and speculating on the impact with respect to patents. Submit the reference along with the publication.

For added fun, hire someone to send the reference and a letter discussing the patent-relevance of the reference directly to the applicant, along with a letter informing the applicant of his/her duty of disclosure with respect to the presentation of both the reference and the letter.

Which points out just why we need a front end filter.

Why exactly do we need a “front end filter” to keep relevant information about claim validity out of the hands of PTO Examiner?

It seems to me the best way to prevent abusive submissions is to require a registration number to make a submission. The registration number would not be published unless the submissions were deemed to be irrelevant or primarily for delaying Examination (rather than assisting Examination), in which case (1) the registration number would be published and (2) the agent/attorney could be sanctioned (e.g., loss of registration number).

That would keep things in line.

Regarding whether or not a preissuance submission may be filed under Rule 290 prior to publication of a patent application, the associated Final Rule appears to list three specific situations in which this is allowed: (1) if the application is abandoned before publication [42152, c.3]; (2) if a non-publication request was filed [42153, c.1]; and (3) if a third party otherwise knows of the application [42166, c.3].

This is different from Rule 99, which allowed third-party submissions only in PUBLISHED patent applications.

Clever.

Which points out just why we need a front end filter.

Look at the PTO’s instructions for filing (link to uspto.gov): if you file online, you’re limited to 250 words per document to “consisely state” the relevance of each document. It appears that the approach to be taken here, where possible, is to first anonymously file third party observations at the EPO and then make those detailed observations – with their detailed explanation of why various claims are knocked out by other publications which will also be submitted – one of publications in the preissuance submission. Then I’m not protesting or opposing – I’m just submitting a document that was submitted in another jurisdiction.

anon, you have me convinced. We need to have a filter between the examiner and a submission such that no statement made by the submitter is ever seen by the examiner.

If potentially relevant, the cited art could simply be made of record with the preliminary examiner stating its legal relevance per the form I suggested below.

I now agree with anon that making any kind of statment whatsoever is a form of protest or opposition. I suggest a simple form that states the legal relevance, the pertinent claims, and, if applicable, whether the art is more pertinent than the art relied upon by the examiner.

The form would be like this

Legal relevance:

1) prior art ____

2) late claim ____

3) double patenting ____

4) other _____

Relevant claim list: ______________

If applicable: Is the art cumulative of art relied upon by the examiner? Yes: ____ No: ____

If you think that you have made a point, I’m sorry but you haven’t.

The problem is the statement of relevance which crosses the line from mere submission of art to a form of examination.

You mean a form of “opposition” right? I’m sure that must be what you mean. See 9/19/12, 1:26 pm.

In any case, you may enjoy equating the submission of art and an accompanying “statement of relevance” with an “opposition” but that doesn’t mean it’s “the law.” And please recognize that I’m just holding you to the standard you insist on applying to everyone else. I’m not saying your position is necessarily unreasonable. I’m responding to your opinion that other positions are unreasonable. I believe your opinion in that regard is difficult to support in light of the facts presented here.

If you want to see an example of an unreasonable interpretation of existing law, I can provide you with one in addition to a crystal clear explanation as to why that intepretation is unreasonable. Just for comparison perhaps, mind you.

the law STILL requires the express written consent for this other form of opposition.

So, the part where the PTO explains that this process is deliberately structured to be the opposite of that…

And here was me thinking that Title 35 was supposed to encourage creative design-arounds.

On the other hand, the Peer to Patent program is for those applicants who have volunteered for the program, meeting the very issue that divides this forum: express written consent.

Note that the law does not bar outright the invovlement of third parties – but it does provide who has the say-so. This is a direct result of the change in US law that moved to publish prior to grant and weighs heavily in the very essence of the Quid Pro Quo underlying the patent system.

Note too, that such volunteer programs are one thing, but forcing an applicant is quite another (for more on this difference, see the Tafas case concerning ESD’s).

You forgot one:

The Director shall establish appropriate procedures to ensure that no protest or other form of pre-issuance opposition to the grant of a patent on an application may be initiated after publication of the application without the express written consent of the applicant.

The problem is the statement of relevance which crosses the line from mere submission of art to a form of examination. Doug’s post at 2:33 belies the fact that this is an other form.

I’m not about to repeat the entire history of the context of this part of the law for you, but the law STILL requires the express written consent for this other form of opposition.

Your example of weather is simply not on point. It hardly even rises to the level of a strawman.

On the one hand, in Peer to Patent, those anti-patent folks chipping in with what they suppose to be relevant art are in a real sense “opposed” to patents being granted on the subject matter claimed for the time being, and actively lodging a “protest” against it.

On the other hand, to dignify any old P2P rant on patentability as an “opposition” strikes me as absurd.

As I see it (above) the law deems a “protest” to be a particular form of “opposition”. So “opposition” is pretty broad, right? And we have to take the law as we find it, right, however dischevelled it is.

See the discussion of the relevant parts of the statute and rules:

link to uspto.gov.

You can file in another country that doesn’t have 18-month publication, a requirement that would preclude filing in most countries, even if you want until just before issuance of the US case to file.

I guess I’ll just do it for you:

35 U.S.C. 122(c).

The Director shall establish appropriate procedures to ensure that no protest or other form of pre-issuance opposition to the grant of a patent on an application may be initiated after publication of the application without the express written consent of the applicant.

The submission of art with a statement of relevance is hardly a “protest … to the grant of a patent.” On the contrary, it’s helping the USPTO do their job and promoting (not protesting) the issuance of higher quality patents (i.e., patents that are less likely to be invalid).

The Director shall establish appropriate procedures to ensure that no protest or other form of pre-issuance opposition to the grant of a patent on an application may be initiated after publication of the application without the express written consent of the applicant.

Again, the mere submission of art with a statement of its relevance to an application is hardly an “opposition” to the granting of any claims that might issue from that application. You might as well argue that I’m “opposing” a weatherman by suggesting that he look out the window before commenting on whether it’s sunny or rainy.

“so convinced that the requirement for “permission” applies to the new preissuance submissions”

…because the new law does not abrogate that section and in fact refers to that section.

This seems almost so rudimentary as to be beyond question – and yet “at least a couple of us” want not just case law cites, but Supreme Court case cites.

Really?

No. Really?

can you point me to any SCOTUS case that says you need a SCOTUS case to have a law seen as law?

No. But I can point you to some sockpuppets who habitually harassed anyone who expressed a view of “the law” without a verbatim court cite except when that view was deemed to be “pro-patent.” Have you forgotten about them already, anon?

You are expressing your particular view of the law. It’s fascinating, although it’s mostly just handwaving at this point. Maybe you can provide us with the specific cite and language of the old rule you are referring to?

And yes most of us are aware of the “canons” of statutory construction. But at least a couple of us are not sure why you are so convinced that the requirement for “permission” applies to the new preissuance submissions. Perhaps you can flesh out your argument a bit more, without the insults?

Thanks.

Dennis Crouch: Question about the second sentence:

“Applicants still have the option of keeping their applications secret while pending. However, that option requires that the applicant forego non-US patent rights.”

If no-public-disclosure, doesn’t an Applicant still have an option to foreign file (without a priority claim to the earlier U.S. application), anytime up to the U.S. issue date ????

Of course, there are disadvantages/risks (later prior art) and advantages (push out fees/fee-decisions & foreign patent term).

Great post Dennis.

You completely misunderstand – you need to establish the need to search SCOTUS case law in the first place, something you haven’t done.

Also, you seem to be getting hung up on a tangent with an ASSUMED conflict – you need to read what I have actually posted (there is no conflict here – Congress not only left in the provision of applicant approval, they tied the new law into “this section.”

You might want to focus on the issue of the thread rather than the tangents.

You mean there isn’t even one SCOTUS case that’s on point? Bummer, if your search of the case law was as exhaustive as you’d have us believe. If I were you, instead of making excuses for the lack of SCOTUS cases, try enlightening us by citing ANY authority for your proposition that the earlier statutory language controls.

As per my comment to MM, can you point me to any SCOTUS case that says you need a SCOTUS case to have a law seen as law?

It’s an interesting legal “theory,” but given the number of laws actually promulgated and the limited availability of the Supreme Court, just not a viable legal theory – so you will have to excuse me for not jumping to find SCOTUS cases for you.

You seem awfully sure of yourself – can you please help us less cocky folks by pointing to the SCOTUS cases that establish your (strange) proposition that the older statutory amendment controls?

Anon, how? How enforced?

How: Assume the examiner relies on a reference that shows all elements (A, B, C) but element D, and D is a secondary reference. The new reference cannot simply show A, B, and C; or D separately. It would have to show A, B, C and D; or something about D in the A, B, C application. Otherwise, the new reference would merely be cumulative.

The PTO somewhat is familiar with this procedure as they use it in reexaminations.

I think the applicant should be entitled to file responsive remarks showing why the purported new reference is merely cumulative. If the submission were determined to be merely cumulative, it should not be used to reject the claims. In addition, that submitter should be barred from providing any further submissions in that application.

The above would reduce, but not eliminate, potential third party harassment by citing cumulative references with some bogus argument about the prosecution.

“But if “opposition” goes undefined, one should not be surprised if people categorize any old observation on patentability as an “opposition” to the issue of a patent.”

And yet, there is not only “surprise,” but people are apparently upset that this thought has taken place.

Maybe I should just “shut-up.”

Maybe not.

“I would all but make it mandatory that a reference not be cumulative of references of record relied upon by the examiner.”

How would you know? How would you enforce it?

“seeing as how you’ve pre-identified anyone who disagrees with you as intellectually dishonest.”

Read my post again – that is decidedly not what I said.

Seriously, are you in the third grade?

Does the word “opposition” have any specific meaning in the context of the AIA?

I ask because, in the context of the European Patent Convention, it does. And so it is, that merely making observations on patentability under Art 115 of the EPC is indisputably NOT opposition.

Looking on from Europe, elements of the 1973 EPC are discernible in the AIA. But if “opposition” goes undefined, one should not be surprised if people categorize any old observation on patentability as an “opposition” to the issue of a patent.

In Europe “opposition” is full-blown adversarial inter-partes proceedings. By contrast, the EPC expressly provides that the observer, by observing, does not make himself a “party” to any proceedings at the EPO. Is there anything of that distinction in the AIA?

[T]here is no intellectually honest way of looking at a third party submission as anything but an “opposition”…

Well, gee, I suppose I can’t argue with that, seeing as how you’ve pre-identified anyone who disagrees with you on this point as intellectually dishonest.

Congratulations.

“I think one form of submission should include bringing to the examiner’s attention the relevance of a document contained in an IDS.”

I think the rules do permit the 3rd party submission to be comments on an already cited prior art reference.

“We all know that the examiners typically do not review in any detail prior art submitted an IDS’s.”

There’s no requirement that the examiners give references submitted in an IDS any more “consideration” than the references that they review as a result of their own search. Nor should there be.

“I seem to recall”

You would be wrong – but thanks for chiming in and advancing the conversation (I did not realize that law had to be litigated to be recognized as law).

Actually, my last two suggestions are somewhat covered here:

From the Fed. Reg., at 42153,

“Additionally, because highly relevant

documents can be obfuscated by

voluminous submissions, third parties

should limit any third-party submission

to the most relevant documents and

should avoid submitting documents that

are cumulative in nature. Third parties

need not submit documents that are

cumulative of each other or that are

cumulative of information already

under consideration by the Office.

Nonetheless, in some instances, third

parties may deem it necessary to submit

a document in an application that was

previously made of record in the

application, where the third party has

additional information regarding a

document that was not previously

considered. Third parties are reminded

that 35 U.S.C. 122(e) requires that the

documents submitted be ‘‘of potential

relevance to the examination of the

application’’ and that the relevance of

each document submitted must be provided in an accompanying concise description.”

I would all but make it mandatory that a reference not be cumulative of references of record relied upon by the examiner.

I would have no problem with the law if Congress did want to change it so that third parties could submit without approval of the applicant – but that’s not the law.

I don’t believe this issue has been litigated so this “permission” requirement for preissuance submissions is actually just your opinion of what “the” “law” “is”, anon. I seem to recall your sockpuppets making similar points ten or twenty times a day not too long.

“Seems to me, to the extent there’s a conflict between the new language and the older language, it’s newer language that trumps – it’s an expression of more recent legislative intent (to the extent that it can be asserted that such a thing actually exists) and therefore should be controlling.”

The problem Doug is that is does not. That’s why I stated that if Congress wanted to make the change, they should have been explicit about it (and you should know that legislative intent only comes into play – maybe – in cases of ambiguity.

There is in ambiguity in what the law still demands.

The Office, attempting to make something ambiguous has been tried before, and failed gloriously (see Tafas).

And in addition to the point above to Leopold, who seems to have joined MM in being a personal troll of mine, I would have no problem with the law if Congress did want to change it so that third parties could submit without approval of the applicant – but that’s not the law.

“seeing as how you’ve pre-identified anyone who disagrees with you as intellectually dishonest.”

Read my post again – that is decidedly not what I said.

A way of preventing protests and oppositions from occurring would to be to require an explanation of why the reference raises a substantial new question of patentability not presented by other references of record. If there are no IDSs or office actions, this requirement should be eliminated by simply stating that or checking a box in a form.

We all know that the examiners typically do not review in any detail prior art submitted an IDS’s. I think one form of submission should include bringing to the examiner’s attention the relevance of a document contained in an IDS.

Agreed. The relevance includes the legal issue.

Yet more proof (as if any more was needed) that the AIA is a pile of $%^& and the folks at the PTO a bunch of weenies. What’s the point of third parties filing publications if NOT to provide the examiner with a basis for a rejection? Let ’em spoon-feed the examiners – what’s an aggrieved party going to do, say it’s an improper rejection b/c someone besides and examiner came up with it? Particularly in the area of software and business methods, the examining corps needs all the help it can get. Time for the USPTO to stop pretending like its in-house people know more about those fields than people who actually work in those fields (and make a gazillion times more money than the PTO examiners b/c they actually have brains).

Seems to me, to the extent there’s a conflict between the new language and the older language, it’s newer language that trumps – it’s an expression of more recent legislative intent (to the extent that it can be asserted that such a thing actually exists) and therefore should be controlling.

Because that’s how statutory construction works — earlier bills control over later ones.

I don’t think that would be appropriate, at least in the eyes of the PTO. In the final rulemaking they stated that the submitter should not propose claim rejections.

Since the permission of the applicant is required for any opposition (…”or other” anyone?) and there is no intellectually honest way of looking at a third party submission as anything but an “opposition,” permission must be obtained.

Well, gee, I suppose I can’t argue with that, seeing as how you’ve pre-identified anyone who disagrees with you as intellectually dishonest.

Congratulations.

Close bold tag.

Somersaults can be set aside with one directive: follow the law.

Since the permission of the applicant is required for any opposition<\b> (…”or other” anyone?) and there is no intellectually honest way of looking at a third party submission as anything but an “opposition,” permission must be obtained.

If Congress wanted to remove that safety check, they should have done so expressly.

Would something along the lines of an international search report be in order? X/Y/A along with paragraph/page numbers and associated claim numbers?