July 2014

Why the USPTO still has no director

Supreme Court Patent Cases Per Decade

Patent Prosecution Bars: My New Article

Interpreting Claims Against The Drafter

Alice being Applied to Allowed but Unissued Patents

Intellectual Property in an Independent Scotland

Trade Secrets, Trademarks, and Interstate Commerce

USPTO Moves to Strongly Enforce Eligibility Limitations

Data Structure Patent Ineligible

SEC Charges Company with Fraudulently Lying about its Patents

Federal Circuit: Administrative Agencies Can Make Rules, But Must Also Follow Them

Jurisdiction over Contempt Finding

Applicant’s IDS Submission of Litigation Documents Constituted Disclaimer

Studying the Mongrel: Why Teva v. Sandoz Won’t Solve Claim Construction

Federal Circuit affirms Rule 12 dismissal of a design patent case

Guest Post By Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

Anderson v. Kimberly-Clark Corp. (Fed. Cir. 2014) (nonprecedential)

Panel: Prost, Clevenger, Chen (per curiam)

In this case, pro se plaintiff Anderson alleged that nine different disposable undergarments infringed U.S. Patent No. D401,328 (the “D’328 patent”). Kimberly-Clark moved for judgment on the pleadings, asserting that it only manufactured five of the nine accused products—and none of those five infringed the D’328 patent. In a per curiam opinion released only two days after the case was submitted to the panel, the Federal Circuit agreed.

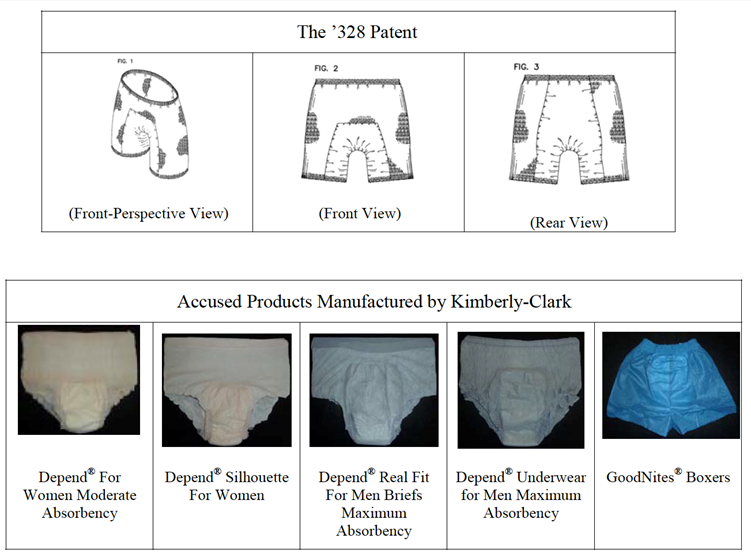

Under Egyptian Goddess, a design patent is infringed if “an ordinary observer, familiar with the prior art designs, would be deceived into believing that the accused product is the same as the patented design.” As these illustrations from Kimberly-Clark’s motion for judgment on the pleadings show, the accused products manufactured by Kimberly-Clark do not even arguably look “the same” as the patented design:

Indeed, in opposing Kimberly-Clark’s motion, Anderson did not even argue that the designs looked alike. And on appeal, her main argument was that the district court erred in considering the images shown above because they were not attached to her complaint. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, concluding that the district court did not err in considering the images because: (1) Anderson did not dispute their accuracy or authenticity; and (2) the appearances of the patent illustrations and accused products were integral to her claims. And ultimately, the Federal Circuit found no error in the District Court’s conclusion that Anderson had failed to state a plausible claim for infringement.

So this was a pretty easy case on the merits. And it is, of course, nonprecedential. But it’s still noteworthy because of its procedural posture. Since Egyptian Goddess, a number of courts have granted summary judgment of noninfringement where, as here, the accused designs were “plainly dissimilar” from the claimed design. But Rule 12 dismissals are still rare. And dismissals pursuant to Rule 12(c) are even rarer. It will be interesting to see if cases like this inspire more defendants to seek dismissal of weak design patent claims at the pleading stage.