Guest Post By Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

Anderson v. Kimberly-Clark Corp. (Fed. Cir. 2014) (nonprecedential)

Panel: Prost, Clevenger, Chen (per curiam)

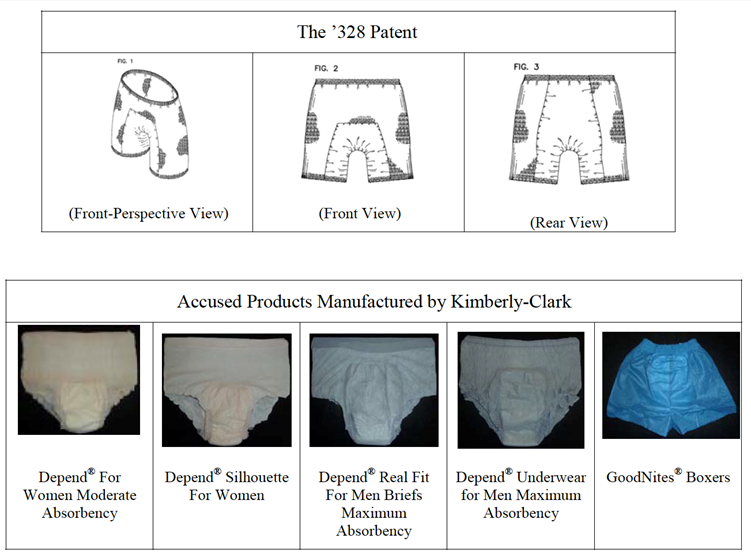

In this case, pro se plaintiff Anderson alleged that nine different disposable undergarments infringed U.S. Patent No. D401,328 (the “D’328 patent”). Kimberly-Clark moved for judgment on the pleadings, asserting that it only manufactured five of the nine accused products—and none of those five infringed the D’328 patent. In a per curiam opinion released only two days after the case was submitted to the panel, the Federal Circuit agreed.

Under Egyptian Goddess, a design patent is infringed if “an ordinary observer, familiar with the prior art designs, would be deceived into believing that the accused product is the same as the patented design.” As these illustrations from Kimberly-Clark’s motion for judgment on the pleadings show, the accused products manufactured by Kimberly-Clark do not even arguably look “the same” as the patented design:

Indeed, in opposing Kimberly-Clark’s motion, Anderson did not even argue that the designs looked alike. And on appeal, her main argument was that the district court erred in considering the images shown above because they were not attached to her complaint. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, concluding that the district court did not err in considering the images because: (1) Anderson did not dispute their accuracy or authenticity; and (2) the appearances of the patent illustrations and accused products were integral to her claims. And ultimately, the Federal Circuit found no error in the District Court’s conclusion that Anderson had failed to state a plausible claim for infringement.

So this was a pretty easy case on the merits. And it is, of course, nonprecedential. But it’s still noteworthy because of its procedural posture. Since Egyptian Goddess, a number of courts have granted summary judgment of noninfringement where, as here, the accused designs were “plainly dissimilar” from the claimed design. But Rule 12 dismissals are still rare. And dismissals pursuant to Rule 12(c) are even rarer. It will be interesting to see if cases like this inspire more defendants to seek dismissal of weak design patent claims at the pleading stage.

It’s a bit of a mystery to me how a per curiam affirmance of a case brought by a pro see plaintiff makes headlines on Patently-O, especially when there are much more interesting things happening in design patent land. For example, in the Apple v. Samsung pending appeal to the Federal Circuit, an amicus brief was submitted by 27 Law Professors (including Prof. Burstein) in support of Samsung arguing that 35 U.S.C. 289, that awards the infringer’s “total profit” on sales of products embodying the patented design, somehow calls for apportionment of the profits between the value of the design and the value of the infringing product that embodies the design. This is contrary to Congress’ Act of 1887 (passed to overturn the infamous Supreme Court opinions in the Dobson carpet cases) upon which section 289 is based, as well as over 100 years of case law that universally says apportionment does not apply to profits awarded for design patent infringement.

Another noteworthy development is that a Petition for Cert. has been filed in MRC v. Hunter et al., a case where the Federal Circuit affirmed the lower court’s granting of a motion for summary judgment that two design patents (on dog jerseys) were invalid for obviousness. The Petitioner is arguing that the current test for combining references in determining design patent obviousness (embodying 60 year old case law) is incorrect in light of the utility patent case of KSR v. Teleflex (which has never been applied in a design patent case). It is an interesting question, to be sure, and the Petitioner relies on an article written by none other than the prolific Prof. Burstein.

I take it then that you disapprove of Prof. Burstein and the pursuit of changing patent law (particularly design patent law) through the courts…

I have nothing but the highest regard for Prof. Burstein. It seems to me that changing the patent statute has always been in the hands of Congress.

“in the hands of Congress”

Not if you pay attention to many academics and their desires as expressed in their friends of the court briefs.

Law professor academics “in support of Samsung” are just that.

Full disclosure: I am writing an amicus brief in support of Apple.

Thanks Perry – the point I am stressing is that many academia feel no compunction whatsoever in advising the courts to re-write patent law (particularly, in the area of 35 USC 101). I realize that this is outside of your specialty, but did note that even in design patents, it appears that wanting a redraft from the courts seems like an ‘easy’ cheap fix as opposed to actually having Congress change the patent statutes.

(no dig at you)

There is little doubt in my mind that the academics’ amicus brief is but a warm-up to Samsung’s legislative push, which will occur a reasonable amount of time after the Federal Circuit rejects their theories (or perhaps is occurring even as we speak..)

Let us please not pay any attention to the desires of academics, patent practitioners, rights holders, Martians, bakers, or anyone else to attempt to change laws through the courts. “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States…” United States Constitution, Article I, Section I. Requesting that a court reasonably interpret a statute to support one’s aims is, of course, not the same as requesting that a court change a statute.

Perry, that is a valuable comment, but I believe the interest here is not in this pro se design patent case per se, but rather in the general difficulty in obtaining a fast and inexpensive disposal of unwarranted design patent suits, given both their unique difficulty in demonstrating non-infringment of a design patent “claim” in a summary judgment motion (as compared to utility patents), and the more difficult old and purely judicially created test for design patent 103 obviousness which has no statutory or Sup. Ct. basis of support. The 103 statute is identical for both.

This is on top of the fact, shown in a survey on this blog just a few years ago, that the USPTO design patent application examiners almost never reject design patent applications on 102, 103 or any other novelty or unobviousness grounds.

[All this of course is not to be confused with design patents infringement damages calculations, which does have a unique statute.]

It just so happens that 2/3 of design patent infringement claims are disposed of on summary judgment of non-infringement, and in the vast majority of those, the court never analyzes the prior art.

Design patent claims by and large are not rejected on prior art in the USPTO, because I believe that the vast majority of designs are the result of original design conception and development, for which it is simply very difficult to find relevant prior art – the goal of most legitimate designers is to design a unique product. Of course, those design patents never make it to court, because they are “obviously” valid.

It is worth pointing out (and often lost in all of the dust-kicking) that far less than 2% of all active utility patents ever make it to court as well.

From the typical QQing, one might be shocked at how low this number actually is. If one were to attempt an objective view of the situation, that is.

Perry is asserting a 2/3 rate of design patent suit disposals on Summary Judgement for non-infringement, which is vastly higher than that % for utility patents [only about 5%, if I recall the reported stats correctly?] whereas almost all the rest of of the 97% of pre-trial case disposals of utility patent suits are due to settlements.

If you have a different statistical source I would be interested in seeing it.

You miss the point of a distorted far less than 2% flea sitting on the tail of the dog wagging the greater than 98% dog.

Perry, I am afraid there may be a considerable number of patent attorneys who will not agree with the proposition that: “Design patent claims by and large are not rejected on prior art in the USPTO, because I believe that the vast majority of designs are the result of original design conception and development, for which it is simply very difficult to find relevant prior art.”

That, for example, every new fender design for every new car can easily get a design patent from the PTO does not mean that those patents immune from a normal 103 test for whether or not its “new wrinkle” car fender was unobvious or not under 103 and KSR standards as compared to other prior art fenders to a fender designer of ordinary skill in that art.

I’m not saying I agree with you Paul, but there are exceptions to every generalization. Anyone out there experiencing a large number of prior art rejections in design patent applications?

35 U.S.C. 289 Additional remedy for infringement of design patent.

Whoever during the term of a patent for a design, without license of the owner, (1) applies the patented design, or any colorable imitation thereof, to any article of manufacture for the purpose of sale, or (2) sells or exposes for sale any article of manufacture to which such design or colorable imitation has been applied shall be liable to the owner to the extent of his total profit, but not less than $250, recoverable in any United States district court having jurisdiction of the parties.

Let’s parse that just a bit.

Assume Samsung made $100billion total profit for all products during the time frame of infringement.

Is the apportionment argument about how much of that was attributable to the tablets found to infringe the Apple design patent?

Nope. The apportionment argument is that, for example, if a design patent covers only a portion of a product, e.g., the upper portion of a sneaker (shown in solid lines) and not the rubber outsole (shown in broken lines), then the profit award should be limited to the profit/value of the upper only, rather than the profit on sale of the entire sneaker.

I should add that this is the view of the Supreme Court in the 1886 carpet cases when they affirmed apportionment between the carpet decoration and the entire carpet. This view was rejected by Congress in the Act of 1887, as embodied by section 289 of the current law. No case since 1887 has apportioned design patent profits in the manner now advocated by the academics.

You may hear the common lament that “times change” and that “policy”/opinion should let the judges over-ride the direct words of Congress.

(the lament is not mine, btw)

“Ordinarily IDSs are not an admission that the prior art is either prior art or material. ”

I am a bit confused by this. Arent IDSs submitted with respect to our duty under 1.56 which refers to materiality?

Yes, but your confusion is natural, as the statute also expressly disclaimed that the submission was an admission.

The Office was more concerned with simply having the material in front of it, and also – importantly – it has always been the duty of the Office and not the applicant to perform the examination. Gen erally, see Tafas.

Yeah, and now if we submit litigation documents, they count as disclaimers.

Who in the world will now submit litigation documents for any reason?

Just the prior art from litigation, and no more.

Still have that duty, Ned….

I wonder if anyone has tried realistic evidentary testing of the fairly recently created “Egyptian Goddess test” by using a survey of ordinary observers presented with something like the media-traditional police line-up. That is, a line-up of photos of the nearest prior art designs, the design patent drawings, and the accused products, to see if the observers can correctly and positively ID ONLY the accused product design from the prior art as being the same as the patented design? Might that be a somewhat more objective way of disposing of unfounded design patent claims [which Fed. Cir. case law says should be narrowly interpreted] on S.J. motions versus just the views of the judge, as here?

I read the post, but not the opinion. Did the P claim there were other pictures that in some small way resembled her design patent? Not sure the post squarely addressed this issue.

No, she did not. It was also the case that several of the accused products weren’t made by the defendant.

MEDISIM LTD. v. BESTMED, LLC.

link to cafc.uscourts.gov

The Federal Circuit reversed a rule 50(b) JMOL that a patent was invalid as anticipated based upon prior use and sales by the patent owner, but affirmed the grant of a new trial.

The JMOL was reversed because the defendant failed to bring a rule 50(a) JMOL motion prior to submitting the case to the jury. Arguments in response to patent owner’s own 50(a) JMOL on lack of anticipation were not deemed sufficient.

However the grant of a new trial was affirmed because evidence was overwhelming that the invention was placed on sale more than a year prior to the filing of a patent application on that invention.

GOLDEN BRIDGE TECHNOLOGY v. APPLE INC.

link to cafc.uscourts.gov

Stipulated claim construction, submitted in IDSs during re-examinations are disclaimers.

The Federal Circuit upholds a finding of noninfringement of reexamined claims based upon a claim construction of the term “preamble,” that was in turn based upon a stipulated construction of the claim term by a district court in a prior litigation, that in turn was submitted to the patent office in an IDS in the re-examination.

Ordinarily IDSs are not an admission that the prior art is either prior art or material. However where the contents of the IDS are the stipulated claim construction by the patent owner himself in a prior litigation, it is binding as a disclaimer on the patent owner unless that disclaimer is clearly rebutted during prosecution.

I’m of two minds on this.

The patent owner seems to have shot himself in the foot. But the whole idea that an IDS is binding as a disclaimer is novel and unsettling.

Think of it on estoppel grounds.

Invite Les to the consideration party.

Ned, isn’t the problem here the way the opinion is written rather than the substantive outcome? It seems to me that the IDS was not what should have been binding as a disclaimer. Instead, it is the stipulated claim construction in the prior litigation. Nevertheless, the opinion muddles the water by putting way too much significance in the fact that the stipulation was submitted in an IDS. Why shouldn’t the previous stipulation as to the meaning of “preamble” be binding (i.e., act as a disclaimer) regardless of whether or not it was submitted in an IDS? I know that collateral estoppel with respect to claim construction in prior litigation can be a thorny issue, but I believe a stipulated construction of a term should be more than enough to invoke collateral estoppel.

Metoo, there is no such thing as collateral estoppel except court to court.

The problem I have is the patent owner may have felt obligated to submit the claim construction to the PTO. He was not advocating anything by this, and I do not see the disclaimer.

But now that we are aware, we can take care to disclaim any disclaimers in anything we file in an IDS.

We need standard language. Maybe the PTO can help.

Perhaps [besides estoppel] because an IPR is an in rem and PTO proceeding, not just litigation between two parties, and is a further PTO prosecution of the same claims, creating additional file wrapper or “prosecution history” for express patent owner claim scope waver or admissions made therein?

“Express” and “therein” are what disclaimers require.

Submitting IDSs that are intended to inform but are not intended to be admissions of anything .. these become disclaimers of scope?

Mein Gott! Anyone would be fool to submit IDSs that include anything from litigation in the future. FOOLs.

F001s or not, the duty to submit remains.

You are not suborning a dereliction of duty, are you?

Duty? Who imposed what duty to whom?

Duty of disclosure, of course – and imposed by Congress.

Congress?

Imposed a duty on the patent owner?

To file with the PTO litigation documents, evidence, testimony what? Subject to protective orders and the like. Really?

Name the statute.

point taken – the duty is from rule, not directly from Congress.

But would you accept authority under law 35 USC 2(b)(2)(A)?

As to “Subject to protective orders and the like,” I recall no such exception to the rule.

Check the footnote. I can’t figure out why KMB just didn’t settle this case.

After all, Ms. Muffin Anderson was only seeking relief in the amount of $50 Billion and “all other fee”.

Just get out that checkbook.

I found this far more entertaining than the merits part of the case: Near the end, the opinion mentions that the pro se plaintiff filed an unopposed motion to amend her complaint for a second time. She argued that the 12(c) judgment was in error because granting that motion was improper and because she also didn’t serve the amended complaint on the defendant. I guess the deference shown to pro se litigants also includes not slapping them with sanctions when they make ridiculous arguments.

APoTU, how can you sanction a pro se plaintiff? Has it ever been done?

Ned — APOTU’s comments reflects his lack of legal training. Ideally, a legal proceeding should be conducted in which both parties have attorneys who zealously advocate their respective positions. However, zealous advocacy does not mean any means possible to advance the client’s position. Lawyers acting badly are sanctioned because (i) they (should) know better, (ii) they bring disrepute upon the profession, and (iii) as a deterrent for future bad acts. None of this applies to a pro se litigant.

The goal of the legal system is to provide justice — not to act as a “gotcha” to the unwary. There is nothing “just” about punishing a pro se litigant.

You’ve found me out, I guess – thanks for the explanation.

That said, I know that the Supreme Court does require payment of docketing fees up front for certain frequent pro se filers of in forma pauperis motions and related petitions, so it’s not unheard of for pro se filers to get themselves in hot water over their shenanigans.

I’m not aware of any monetary sanctions, Ned, but I’ve seen a situation where a repeat pro se plaintiff was subjected to an order under which any future filings in federal court had to go through the sanctioning judge first. There’s not a whole lot you can do with a judgment-proof, delusional, pro se plaintiff except try to minimize the costs to the defendants. That’s what the court is doing here – they’ve seen these people before.