Guest post by Professors Jonathan S. Masur (UChicago Law) and Lisa Larrimore Ouellette (Stanford Law).

In our 2024 Stanford Law Review article, “Real-World Prior Art,” we argued that the doctrines surrounding the public-use and on-sale bars—categories of prior art that we collectively called “real-world” prior art—were in some respects confused and misaligned. One of our arguments was that private sales—sales in which the invention has not been put into public use or led to the creation of some other type of prior art—should not provide the seller with a safe harbor against prior art under post-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b)(1)(B), because a private sale by itself does not “publicly disclose” the invention per the terms of the statute. Not long after the publication of our article, the Federal Circuit held just that, in an excellent opinion by Judge Dyk, Sanho Corp. v. Kaijet Tech. Int’l Ltd., 108 F.4th 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2024).

A related argument in our paper—perhaps the central argument—was that the on-sale bar should be “party-specific.” That is, a sale by Aleida, by itself, should not bar independent inventor Bruno from obtaining a patent. Of course, the sale will often lead to the buyer putting the invention into public use, or generate a printed publication, or create some other type of prior art against Bruno. But the sale by itself should not bar Bruno. In our paper, we offered a suite of reasons why this should be the case:

- Unlike the public-use bar (which is about protecting the public’s reliance interests), the on-sale bar is animated by the goal of preventing any one party from obtaining monopoly profits for more than the twenty-year statutory patent term. Accordingly, the principle behind the on-sale bar is not implicated if Aleida makes a sale but then Bruno files for a patent.

- For decades, dating back to the famous Learned Hand opinions in Metallizing v. Kenyon Bearing and Gillman v. Stern, and including the canonical 1983 Federal Circuit case Gore v. Garlock, the courts of appeals have treated instances of secret commercial use as party-specific. Only the party engaged in the commercial use was barred from later obtaining a patent. Secret commercial use is best understood as a species of putting the invention on sale, so the same principle that applies to secret commercial use should apply to the on-sale bar writ large.

- A private sale does not publicly disclose the invention or enrich the store of public knowledge—that’s why it doesn’t trigger the § 102(b)(1)(B) safe harbor. Treating the on-sale bar as party-specific thus creates incentives for otherwise-secret inventions to be publicly disclosed by allowing a second party to patent the invention.

- If the on-sale bar were not party-specific, an odd situation could arise in which Aleida made a private sale, then Bruno immediately filed for a patent, and then Aleida immediately filed for a patent, and neither of them was able to obtain a patent. Aleida’s sale would bar Bruno but not protect Aleida under § 102(b)(1)(B). Aleida would then be barred by Bruno’s patent filing. This would contradict the intended structure of the America Invents Act, in which the first party to publicly disclose the invention should be entitled to a patent.

As it turned out, the caselaw in this area was highly muddled. On several occasions, the Federal Circuit had stated that the on-sale bar was party-specific and would bar only the party that made the sale. On several other occasions, the Federal Circuit had stated that the on-sale bar was not party-specific and would bar everyone. At the same time, all but one of the cases in which the Federal Circuit stated that the bar was party-specific involved an additional type of prior art—the sale had led to public use, or a printed publication, or some other type of prior art. That called into question whether the Federal Circuit had really intended to hold that the sale by itself was enough to bar third parties from patenting. The situation in the district courts was no clearer, with cases going in every direction—including on October 23 in the District of Delaware. We closed that section of our paper with the plea: “At minimum, the court should clarify this area of law definitively, lest practitioners and lower courts remain at sea.”

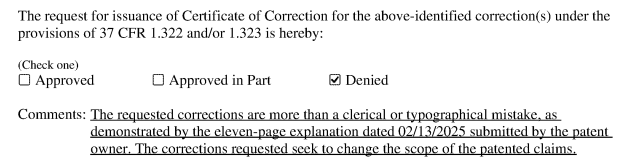

An opportunity has arisen for the Federal Circuit to do just that. In Cellulose Material Solutions v. SC Marketing Group (2024), a judge in the Northern District of California held on summary judgment that an April 2016 purchase order from a company called Thermal Shipping invalidated a patent filed in June 2016 by a separate company called Cellulose Material Solutions. The court also stated that Thermal Shipping did not actually deliver the invention to its customer until July 2016, after Cellulose’s filing date. Accordingly, the only prior art that existed as of the time of Cellulose’s filing was Thermal Shipping’s third-party sale—the invention could not yet have been put into public use. Cellulose has appealed the decision to the Federal Circuit, arguing that the April 2016 purchase order cannot, on summary judgment, be held to invalidate its patent under § 102(a)(1) and the § 102(b)(1) exceptions, including due to disputed factual issues.

We filed an amicus brief supporting Cellulose, arguing that the district court got the law wrong and urging the Federal Circuit to clarify, definitively, that the on-sale bar is party-specific and third-party sales, by themselves, do not bar unrelated inventors from obtaining patents. We are grateful to the excellent faculty and students at the Juelsgaard Intellectual Property and Innovation Clinic at Stanford Law School who helped write and file the brief for us. We have no financial interest in the outcome; we would simply like to see the law clarified in a sensible way, and we hope the Federal Circuit sees the issues as we do!