In an earlier article, I noted that only 25.6% of recently issued design patents received at least one rejection during prosecution. I wanted to develop a better understanding of the reasons for rejections, I filtered for recently issued patents that had been initially rejected during process and then pulled-up their file histories using PAIR. For this study, I looked the first non-final rejection of only 86 file wrappers, but even that small number of cases showed a dramatic result.

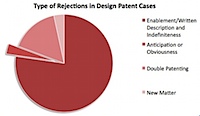

In my sample, the first non-final rejection came in some combination of six basic forms: anticipation; obviousness; lack of enablement or written description; indefiniteness; new matter; and double patenting.

The surprising results are that only 3.5% (3 of 86) of the rejections were prior art related rejections. In three of the cases, the examiner rejected the pending application as obvious in light of the prior art, and in one of those cases the examiner also asserted that the claimed design was anticipated by the prior art. In the remaining 83 cases, the examiner conducted prior art searches but indicated that the claimed design was patentable over the art. Combining probabilities: My data indicates that fewer than 1% of recently issued design patents ever received a novelty or anticipation rejection. (At 99%CI, this may go as high as 2.5%). In other words, design patent applications sail through the PTO.

Although design patent prosecution does not have much focus on inventiveness, examiners are keen to ensure that the scope of the patent claim (via the drawings) is well defined. The most common rejection in my sample was based on confusion created by the drawings. In a design patent application the drawings represent the majority of the specification and also define the claim scope. Thus, it makes sense that confusing or inconsistent drawings would lead to rejection based on both the first and second paragraph of 35 USC 112. In my sample, 79.1% of the rejections (68 of 86) raised a combination of both lacking enablement/description and indefiniteness.

16.2% of the rejections (14 of 86) included an obviousness-type double patenting rejection against an applicant's own previously-filed application. Those rejections are curably through a terminal disclaimer. However, some applicants prefer to argue over the rejection and save patent term. Finally, 3.5% (3 of 86) of rejections focused on new matter added during prosecution. Often, the new matter was allegedly added when the applicant submitted pen and ink drawings to substitute for photographs found in the original.

A Registration System: My data indicates that our design patent system is approaching a registration system. But, there is no problem with a system of design registration - especially if design patents continue to be narrowly construed. Europe's design registration is working well as are the US systems of trademark and copyright registration. In the US, most property rights are registered or recorded rather than thoroughly examined, and those lower-cost mechanisms should probably be the default unless we have some reason to believe that thorough examination is necessary.

Notes:

- See, Dennis Crouch, Design Patents: Sailing Through the PTO, Patently-O (April 2, 2009).

- My samples of recently issued design patents consists of design patents issued Feb-April 2009.

- As I mentioned in the earlier post, these numbers are a bit skewed because the file histories of abandoned design patent applications are kept secret by the PTO unless used as a priority document. Just under 20% of design patent applications are abandoned during prosecution, and I suspect that a greater percentage of those are rejected during prosecution. This consideration would thus skew the results for someone considering the likelihood that a pending design patent application will be rejected.

- In an upcoming paper (not yet available) I note that design patents are often used as substitutes for trade-dress protection, but that the overlapping of regimes does not create significant problems.

bleedingpen,

It is common knowledge that a patent is a right to exclude, not a right to use. I agree that you can use expired subject matter, but I disagree that a patent is a right to use or a monopoly, which implies a right to use, before the patent is expired. A patent is a right to exclude. Upon expiry, that right to exclude is gone. If you want to say that gives others the right to use, that is fine, but it confuses what the right is in the first place. Also, it may ensnare the unweary who think that after-arising improvements that build upon the now-expired-patented-technology can also be copied, when in fact those after-arising improvements may actually be patented, in which case the copyist is an infringer notwithstanding that what has been copied includes the now-expired-patented-technology.

As to the design patent and trade dress issue, I would not anticipate this “troubling” issue getting to the Supreme Court level or even en banc Fed Cir any time soon.

Um … you who believe trade dress shouldn’t be able to extend IP rights past the expire of design patents do realize that a paradox is the result … in that a company would (supposedly/apparently) then be better off not even bothering with a design patent at all … and instead quickly (and expensively) attempt to establish trade dress protection … so that they wouldn’t LOSE protection once the design patent expired.

What I don’t think Congress had in mind was:

Design patent = future lost trade dress rights

bleedingpen says: “It is the quid pro quo of the patent system that the public gets the right to use the subject matter of an expired patent.”

Confused says:

“That is not true, and I certainly would never advise someone of that. A patent is not a right to use, or a monopoly as you call it, but rather a right to exclude. The quid pro quo is not that the public gets a right to use after patent expiry, but rather the benefit of the inventor having disclosed to the public his idea or design. The public benefits because a new idea or design has been disclosed, and the public can build upon that new idea or design. However, the public still must be weary of infringing other patents *****(think: after-arising technology)**** or any trade dress rights that have accrued in the interim.”

After arising technology shouldn’t be the subject of a valid patent if the subject matter was disclosed in the expired patent.

And on the public’s right to use the subject matter of an expired patent, I point you again to Special Equipment, or as Saidman also points out, Kellogs and Old Singer.

Confused says:

“The elements of design and trade dress are different, and this too makes bootstrapping fair.”

Well at least you are admitting that it is boot strapping. The elements of each respective claim are very very similar and have a good amount of overlap. One doesn’t necessarily lead you to the other, but as I wrote earlier, it gets you half way there.

Confused says:

“[U]se-in-commerce does not come with the design, and merely because the producer can exclude others, does make establishing use in commerce any easier.”

I agree, it does make establishing use in commerce much easier.

Confused says:

“It seems fair to conclude that since the producer came up with the original design, he shold have a right to exclude others from copying it, no?”

Exactly, and he has two avenues for protecting that right- the design patent with its ultra low standards for patentability and a limited 14 year exclusionary right, or trade dress with its more difficult standards and an indefinite period of exclusionary right so long as those more difficult standards and met and continued to be met. He shouldn’t get both, particularly when extending the protection beyond a limited period of time conflicts with the basic quid pro quo of an expired patent.

And Saidman,

I completely agree, the Supremes have got to revisit this and give us or reaffirm some good case law.

Mr Saidman, I take it from your piece that shape marks, like a Coca-Cola bottle, are not registrable as trademarks, in the USA. I can envisage a patent expiring, and the invention becoming free to copy, but not the shape of the bottle in the drawings because, by then, it’s a valid and in force trademark registration.

And, in that case, what about the interim protection of the shape, through a design registration?

Carani makes a good point. Another reason obviouness rejections are rare is because when a designer sits down to design a new product, most of the time they are trying to design something distinctively different from the prior art, not something that follows the trend. Hence, the design ain’t obvious as a matter of fact. This is different from utility practice in that a lot of inventions build incrementally on the prior art, and are thus much closer to it, and are thus much more likely to draw 103s. BUT, keep your eye on the Titan Tire design patent case pending at the Federal Circuit (for almost a year) where the court will decide if, when and to what extent KSR will apply to design patents. If KSR is wholly adopted as part of design patent jurisprudence (a bad idea – the last thing we need is a subjective patentability standard when it comes to admittedly subjective designs), then you’ll presumably see a lot more 103s in design applications.

Sooooooooooooo much material, it is hard to know where to start. So, I start with confused SCOTUS (confused indeed), who should start by reading the old Singer v. June and Kellog v. National Biscuit cases from the unconfused [real] SCOTUS. These cases, which the federal judiciary has by and large lost sight of over the years, clearly held that the public has a right to copy the subject matter of an expired patent (utility or design). There are a LOT of subsequent SCOTUS cases that support this underlying public policy undergirding the patent laws. I don’t see how the public’s right to copy the subject matter of an expired patent squares with the producers right to exclude others from using the same subject matter. Someday the right case will present itself to the SCOTUS where they will reaffirm this (they had a chance in TrafFix, but sidestepped it, deciding that case instead on the comparatively easy issue of functionality).

bleedingpen,

I still do not see the unfairness. It is fair for a producer to develop a trade dress worthy of design protection as well. In fact, this seems to give an advantage to the small producer, since without such a foot-in-the-door system a large producer could simply come right in and swipe the trade dress away from the small producer. The elements of design and trade dress are different, and this too makes bootstrapping fair. Not all designs will serve as a source-identifier, and simply because the producer can exclude others, alone, will not establish the design as a source-identifier. And you call it a monopoly. It is not a monopoly because the producer does not have a right to use, only a right to exclude. More on this later. So, the producer may still have to pay a licensing fee to others to use his design, assuming it incorporates features of other designs. Who pays for that? And as mentioned, use-in-commerce does not come with the design, and merely because the producer can exclude others, does make establishing use in commerce any easier. Who pays for that use-in-commerce? It seems fair to conclude that since the producer came up with the original design, he shold have a right to exclude others from copying it, no? It seems fair, then, that if during this exclusionary period, the producer also works hard and spends much money establishing the design as a source-identifier and use-in-commerce, then he should also be rewarded with a trade dress right, no? What am I missing here? This is getting back to basic patent law and trade dress fundamentals. None of this to me is troubling.

bleedingpen says: “It is the quid pro quo of the patent system that the public gets the right to use the subject matter of an expired patent.”

That is not true, and I certainly would never advise someone of that. A patent is not a right to use, or a monopoly as you call it, but rather a right to exclude. The quid pro quo is not that the public gets a right to use after patent expiry, but rather the benefit of the inventor having disclosed to the public his idea or design. The public benefits because a new idea or design has been disclosed, and the public can build upon that new idea or design. However, the public still must be weary of infringing other patents (think: after-arising technology) or any trade dress rights that have accrued in the interim.

Ok ok, so those topics aren’t the best.

Here’s one!

Tafas v Dudas ROUND 3 FIGHT!

link to ipwatchdog.com

“Global warming caused by man, fact or fiction?”

Nice strawman. The issue is not what “causes” climate change but whether human behavior (e.g., emissions from factories and automobiles, combined with changes to the landscape) can exacerbate such changes for the worse.

Of course, when framed that way, the vast numbers of m0r0ns in our culture can’t grasp the issue. Also, they run into the problem that only nutjobs and professional gadflies dispute the universally acknowledged answer to the question.

Dear Professor Crouch,

Question: Can I trademark “(©¿®)”?

Dear Number Six,

Re: “5. Global warming caused by man, fact or fiction?”

Heck — I’ve even say it heard it said that, if it wasn’t for a man’s causing global warming, we’d be in an Ice Age (©¿®)™.

“Of course, more indicative of lack of anything else compelling, but not shabby nontheless.”

Yes, we need something to squabble about. Anyone biting on:

1. Obviousness in light of KSR.

2. In claim species restrictions.

3. Patent Hawk’s patent, valid/invalid? Bilskied?

4. How’s your practice doing? I’m getting reports of the firms I work with losing a lot of business. Some of my bud’s firms lost all but 30% of their work from one company going under.

5. Global warming caused by man, fact or fiction?

6. Creator of the lunocet, better human being than your clients?

29 posts on a “design patent” topic.

Not too shabby.

Of course, more indicative of lack of anything else compelling, but not shabby nontheless.

“Circling back to the headline, the notion that design patents are “sailing through” the system is a wee bit misleading. The reason design patents “sail” through the system, and are unlikely to receive a prior art rejection, is because patent practioners draft ultra-narrow design claims.”

LOL.

Ah, not my field, Punches. In common law UK the petitioner for revocation would need to get to a preponderance of evidence to make out his case for revocation. In civil law mainland Europe there isn’t really much in the nature of “Rules of Evidence” and so you should think in terms of the “balance of probability” and the “unfettered consideration of evidence” by the tribunal. But the same principle still applies. Registered is valid, till somebody manages to prove the contrary.

Of course the big mystery, with the new-fangled right called “European Design Registration” that operates without claims and a specification, until we get more caselaw, is what is the scope of protection given by any particular Registration. Somebody on this blog used the terminology “smell test”. That might fit.

Does anybody know the qualifications required to become a design patent examiner? Are they engineers, or design professionals, or both, or neither?

Max–

Your comment presumes that the design is new. Since a non-registrant can presumably challenge a registered mark on a novelty basis, which party then bears the burden of proof of novelty or non-novelty? And what is the standard of proof required?

Sorry to tread the same old ground…

Circling back to the headline, the notion that design patents are “sailing through” the system is a wee bit misleading. The reason design patents “sail” through the system, and are unlikely to receive a prior art rejection, is because patent practioners draft ultra-narrow design claims. All too often, I see design patents that include every little detail in solid lines. (e.g. threading on a bottle cap, structual support, injection molding flash artifacts!!) It is critical to note that with design patents, every solid line in the drawings is equivalent to a claim limitation. A cursory review of the Gazette shows that applicants still include loads of unneccessary detail in their design drawings, despite the 1980 In re Zahn decision which permits the use of dotted lines to disclaim portions of the design.

In utlity patent speak, a design patent drawing with loads of detail in solid lines is equivalent to filing a utility patent claim with paragraph after paragraph of claim limitations (i.e. a picture claim). In both situations, one is unlikely to receive a prior art rejection – the claim is ultra-narrow. There is little reason for alarm, however, for at the end of the day, narrow patents (with loads of claim limitations) are interpreted narrowly…

This idea of a design registration protecting a new shape mark, till the mark has become distinctive through use, seems pretty simple to me. But then I’m just a naive European who is familiar with the use of European design registrations to achieve that objective but who doesn’t understand trade dresses. Let’s take the hobbled skirt COKE bottle, when it was new. Without a design registration it would have been fair game for imitation by all the other soda pop makers. But with its childhood protected by the rights given by design registration, it has the chance to become a valid trademark registrable as such. And where’s the harm in that?

Confused,

“By the patent laws Congress has given to the inventor opportunity to secure the material rewards for his invention for a limited time, on condition that he make full disclosure for the benefit of the public of the manner of making and using the invention, and *****that upon the expiration of the patent the public be left free to use the invention.”***** See Special Equipment Co. v. Coe, 324 U.S. 370, 378, 65 S.Ct. 741, 745.

Confused says:

“How does trade dress protection “artificially” extend design patent protection?”

I will get to that with the rest of my answers.

“The producer must still pay the fees for obtaining the desing patent and maintaining it for 14 years in the first place.”

Actually there aren’t any maintenance fees for a design patent, and the filing fees, issue fees, etc that the patentee pays are for securing that 14 year right, not for extending that right into the distant future with a trade dress claim.

“But that 14-year right to exclude alone will not garner a producer any trade dress protection. If the producer does not use the design in commerce, then he will not be able to obtain any trade dress rights.”

Absolutely, but if he isn’t using the design in commerce, then he won’t likely be pursuing trade dress claims. The point is that the design patent monopoly gets you halfway to meeting all of the elements necessary for a trade dress claim.

“It seems fair to allow a producer to obtain a patent on a design and utilize his patent rights for 14 years, and if in the meantime the producer also establishes use in commerce, then he should also deserve trade dress protection.”

To get the trade dress claim, he also has to establish that consumers associate the product with a certain origin. But wait, he has a 14 year monopoly where no one else can practice the invention, and, as you should be able to discern, it won’t be difficult to establish origin if you are the only producer vis a vis the design patent rights.

“Basically it amounts to a 14 year biding-time trademark warehouse right for the producer to determine if he desires to transition the design right into a trade dress right.”

Fair enough, though my experience has been that producers rarely think about trade dress (I don’t think most attorneys even understand it), until they don’t have any other IP claims left, such as say when their design patent has expired.

“In fact, in my experience it has usually been the case that the producer starts using the design in commerce at the time he files the design application. In other words, the design warrants trade dress protection as well, even before the patent expires.”

The design doesn’t warrant trade dress protection until it has established origin. The design can’t establish origin without some period of time of marketing, establishing good will, etc. But wait, pursuant to the rights granted by the design patent, the producer has the right to stop someone from making a confusingly similar copy of their design. I seriously doubt many designs have even come close to establishing trade dress protection at the time of their filing, since they have at most one year before filing the design patent application.

“In this sense, it is not an extension at all, but rather protection from a different IP angle.”

Call it what you want. It is the quid pro quo of the patent system that the public gets the right to use the subject matter of an expired patent. Trade dress protection after the expiration of a design patent thwarts this public policy.

“But why does this trouble you?”

I think I have explained that.

SCOTUS, good question. But formalities is not really my thing.

Since April 01, 2009 a great deal of “re-formatting” is going on, to deprive the EPO of its new fee, per page, on each new application filed. I’m not in the day to day hubbub, but I think the fee bites on PCT apps AS FILED, so it’s too late to avoid the fee by re-formatting on entry into the EPO regional phase. I have seen some stunning figures recently, of the huge number of pages saved, when we re-format new jobs arriving before the end of the Paris year and before we file them at the EPO.

So, my advice would be, read Rule 49 EPC 2000 before formatting your PCT specifications.

No para numbering required. The EPO computer will do that. See Rule 49(7) for the “preference” that every 5th line be numbered.

MaxDrei,

Off topic, are European patent applications required to be submitted with paragraph numbering? If yes, what word processor do you (or your administrative assistant) recommend for doing so, and how is paragraph numbering added?

Punches: European design registrations are exclusive rights, like utility patents, so wider than just a protection against copying. “I didn’t copy” is no defence to a claim that a European Design Registration has been infringed. The practical value of a certificate, issued by authority, giving the holder exclusive rights and valid till proved otherwise I hardly need to emphasise, to an American readership.

“Creativity” is the design patentability test, Malcolm?”

Oh no you didn’t.

“Creativity” is the design patentability test, Malcolm?

curious: “Dennis, do you think that more prior art rejections should be made? If so, why?”

curious, do you have an opinion of your own? if so, what is it? if not, please visit the USTPO website and look at the last twenty design patents that issued and let us know which of them strike you as the least creative.

then we will have a great starting point to address your concerns.

“Basically it amounts to a 14 year biding-time trademark warehouse right for the producer to determine if he desires to transition the design right into a trade dress right.”

And that’s exactly what Congress intended it to be.

Right?

bleedingpen,

How does trade dress protection “artificially” extend design patent protection? The producer must still pay the fees for obtaining the desing patent and maintaining it for 14 years in the first place. But that 14-year right to exclude alone will not garner a producer any trade dress protection. If the producer does not use the design in commerce, then he will not be able to obtain any trade dress rights. It seems fair to allow a producer to obtain a patent on a design and utilize his patent rights for 14 years, and if in the meantime the producer also establishes use in commerce, then he should also deserve trade dress protection. Basically it amounts to a 14 year biding-time trademark warehouse right for the producer to determine if he desires to transition the design right into a trade dress right. In fact, in my experience it has usually been the case that the producer starts using the design in commerce at the time he files the design application. In other words, the design warrants trade dress protection as well, even before the patent expires. In this sense, it is not an extension at all, but rather protection from a different IP angle. But why does this trouble you?

“The surprising results are that only 3.5% (3 of 86) of the rejections were prior art related rejections.”

Dennis, do you think that more prior art rejections should be made? If so, why?

“(Speaking of which, I miss the old days, when business method patent apps were an easy sell”

The PTO is still issuing horrifyingly crappy biz method patents on a regular basis.

link to 1201tuesday.com

Hi Punches and thanks. Sorry, it’s late and design patents are boring. Can’t find it in me to formulate any reply, much as I’m flattered to be asked.

I’ll admit, I did get some lulz from USD408,821 and USD384,488.

Michael–

I had a good laugh when I checked out USD408,821 and USD384,488.

Thanks very much–I urge others to look at these as well.

Design patents might not be worth much, but they are a pretty painless way of making some extra cash if you are a patent lawyer. (Speaking of which, I miss the old days, when business method patent apps were an easy sell and clients were buying.)

Dear Dennis,

My favorite reference for design scope thus far remains USD408,821; and for illustrating differences in patentability between utility and design to be USD384,488 and the “not citable” 1995 Fed. Cir. case of Jore Corp. v. Kouvato, Inc.

Because scope and drawings are so intimately tied in design patent law (where the name of the game is “the drawings”), one might also be interested in how many of your samples were from original design patent applications that included multiple embodiments (that also were not later divided out and prosecuted separately). As an aside, the record figures for an issued design that I know of thus far is USD 462,255 (having 336 figures).

If you are also contemplating crossover subject matter (CIP between design and utility remains a tricky noun in design patent land), examples of this include: (a) from utility to design, the family: US6,486,862; US6,486,862; D427,587; and D420,671; and (b) from design to utility D427,805; D429,089; and US 6,220,681.

A design patent gives a producer a 14 year monopoly on the ornamental features of their design. If they police this right, then the design becomes distinctive and consumers associate it with one particular producer. At the conclusion of the 14 year patent term, then the producer has most of the elements necessary for a trade dress claim and those elements are attributable to the existence of the design patent. The producer can them claim trade dress protection and artificially extend the protection of their design patent.

This troubles me.

Yes, it IS basically like a registration system, and the “claim scope” is accordingly narrow–perhaps uselessly so.

Why not allow, in design patents, claims of the same type used in utility patents? There’s no reason one can’t describe a combination of ornamental features in prose form just as they can a combination of utilitarian features. Then design patents might become useful.

Yes, why are design patents not just administered under the copyright regime?

They could fall within the “artistic” category–after all, what is ornamental is by definition not functional, and therefore not the province of utility patents.

Even if the design were capable of being repeatedly applied to a vast number of tangible articles, there is always a “first” article to which it is applied, after which all others are copies or reproductions.

MaxDrei suggested to me in an earlier post that the policing of old designs in europe might be proceeding on a copyright basis, as the physical representation of a copyrighted design. If that is indeed the case, and copyright can be used successfully, then why in europe do they have the parallel system of design registration? Are the rights that different? Is design registration more harmonized and therefore more practical in europe than is copyright? MaxDrei?

No no, not peer-to-peer…just make designs a registration system like copyrights. Why waste everyone’s time? The reason there are so few prior art rejections is not that the examiner’s can find the design, it is that the exact design is original. Picture claims are hard to meet. In the rare case that it isn’t then take it to court.

Further, since most of the errors seem to be on applicant’s filing inconsistent or improper drawings then when they file crap…they get crap.

Ha. Maybe they should do that for utility patents too, that might get the attorneys to write some proper claims from the beginning.

Dennis–

Do you have any idea how many of your sample were prosecuted pro se, or at least how many that were rejected on written description/enablement were pro se?

I just received a NOA yesterday on a design patent, in a FOAM, although it was a divisional.

The references cited have basically no similarity to the claimed design, whatsoever.

I believe that design patents could be the single most valuable area to implement a peer-to-patent type of program, to overcome the obvious difficulty of searching.

To support this belief, I cite–who else–myself! (I know the “coalition for whatever” will be all over me). Here is part of a post I made on another design patent thread:

“The prior art of designs is not quickly and easily searchable. The single best, and most usefully searchable, resource for prior art, and its comparison to the claimed design, is the human mind. The value of an experienced designer, or observer of designs, or market participant cannot be underestimated. They represent an immediately accessible repository of design knowledge and awareness that is unmatched by any externally available system.

Also, in my experience, development of designs is not as cumulative as development in utility fields, where you often have to know everything that came before in order to take the next step and end up with something patentable. A 4-year-old child can render a patentable design in minutes. This makes the field of prior art immense, diffuse, and poorly documented.”

And therefore ripe for peer-to-patent.