New PTO Fees: Up 5% to account for inflation. [LINK]

- Patently-O Job site has a new media partner: the Inhouse Blog. The Inhouse blog has its own job board with inhouse jobs.

- Duffy Provision: Duffy expressed his "skeptic[ism] about the constitutionality of the retroactivity provision." [LINK]

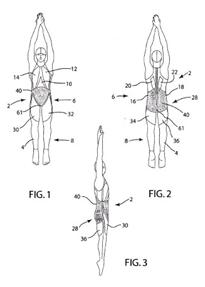

- Speedo's torso-swimsuit patent is still pending. See http://www.pat2pdf.org/patents/pat20080141431.pdf.

New PTO Fees: Up 5% to account for inflation. [

New PTO Fees: Up 5% to account for inflation. [

“the majority of swimmers bought it could be due to aesthetics” — competitive swimmers are concerned about how fast they are, not how they look

Furthermore, a commentator noted during the swimming coverage that 3-meter deep pools like “the cube” were faster than the standard (and most commonly used) 2-meter deep pools due to less turbulence.

Furthermore, a commentator noted during the swimming coverage that 3-meter deep pools like “the cube” were faster than the standard (and most commonly used) 2-meter deep pools due to less turbulence.

The experiment would have to be designed to account for the placebo effect. If you think the magic suit will make you go faster, then it just might. The effect might further be positively compounded within a group, such as all swimmers in and around the watercube.

Lowly, the fact that the majority of swimmers bought it could be due to aesthetics. It sure is a snappy piece of water sporting apparel. Roaring 20s style is coming back, ain’t it?

“So I’d expect the examiner to argue that the commercial success of the swimsuits is not commensurate in scope with claims to garments.”

In that regard, do the claims refer to the relative buoyant nature of the garment versus the prior art swimming garments?

>

experiment shouldn’t be very hard to conduct

— how about declarations from swimmers who attest to their improved swimming times

A couple of points:

1. Claim 1 is directed to a garment, not a swimsuit, and just before the claims the specification states, “The principles exemplified above can also be applied to other specialist sports garments, especially wet sports such as waterpolo and triathlon and beach sports such as beach volley[ball].” MPEP 716.03(a) provides that

Objective evidence of nonobviousness including commercial success must be commensurate in scope with the claims. In re Tiffin, 448 F.2d 791, 171 USPQ 294 (CCPA 1971) (evidence showing commercial success of thermoplastic foam “cups” used in vending machines was not commensurate in scope with claims directed to thermoplastic foam “containers” broadly).

So I’d expect the examiner to argue that the commercial success of the swimsuits is not commensurate in scope with claims to garments.

2. also, from the same section of the MPEP

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit stated in Stratoflex, Inc. v. Aeroquip Corp., 713 F.2d 1530, 1538, 218 USPQ 871, 879 (Fed. Cir. 1983) that “evidence rising out of the so-called ‘secondary considerations’ must always when present be considered en route to a determination of obviousness.” Such evidence might give light to circumstances surrounding the origin of the subject matter sought to be patented. As indicia of obviousness or unobviousness, such evidence may have relevancy. Graham v. John Deere Co., 383 U.S. 1, 148 USPQ 459 (1966)

and

The submission of objective evidence of patentability does not mandate a conclusion of patentability in and of itself. In re Chupp, 816 F.2d 643, 2 USPQ2d 1437 (Fed. Cir. 1987). Facts established by rebuttal evidence must be evaluated along with the facts on which the conclusion of a prima facie case was reached, not against the conclusion itself. In re Eli Lilly, 902 F.2d 943, 14 USPQ2d 1741 (Fed. Cir. 1990). In other words, each piece of rebuttal evidence should not be evaluated for its ability to knockdown the prima facie case. All of the competent rebuttal evidence taken as a whole should be weighed against the evidence supporting the prima facie case. In re Piasecki, 745 F.2d 1468, 1472, 223 USPQ 785, 788 (Fed. Cir. 1984).

So, I’d expect the examiner to come back with the argument that the commercial success of the swimsuits does not provide facts that are relevant to the state of the art at the time the invention was made and therefore fails to “give light to circumstances surrounding the origin of the subject matter sought to be patented” and, thus, is given no weight against the evidence supporting the prima facie case.

3. And I’d also expect the argument that an incremental improvement in swimming speed is neither unexpected nor surprising. And as Duckworth noted, unless you have a controlled experiment where the same swimmers use the old and new suits, how do you know that it isn’t the swimmers that are improved, and not the suit?

I’m presently prosecuting a case where we’ve submitted evidence of commercial success, and we’ve tried to head off these kinds of come-backs. I’ll be surprised, however, if it gets any traction. Happily, I think the better argument is that the examiner is modifying the primary reference in a way that it would not work for it’s intended purpose…

Duckworth,

The better argument is to show that a very large percentage of the swimmers in the olympics used the suit as soon as it was available. I believe that secondary consideration is called commercial success 😉

“With respect to the commercial success of the claimed invention, Applicants respectfully submit Exhibit A, Mr. Michael Phelps, as evidence of the unexpected and surprising results which confirm the nonobviousness of the invention.”

Examiner reply: Correlation does not equate to causation. In other words, Phelps is a darn fine swimmer with or without the suit.

“surprising results which confirm the nonobviousness of the invention”

I agree that there are good secondary considerations on this. BHR, I think your point provides an even better nexus between secondary considerations and the claims. Unfortunately, with the (independent) claims in their current state, it’s looking like a 102, not 103, rejection.

Its not just Phelps – at one point the announcers were saying that 44 out of 48 swimming medals won to that point in the Olympics had been won by swimmers wearing the new suit.

I’d like to be the attorney/agent prosecuting the Speedo patent application.

“With respect to the commercial success of the claimed invention, Applicants respectfully submit Exhibit A, Mr. Michael Phelps, as evidence of the unexpected and surprising results which confirm the nonobviousness of the invention.”