Guest post by Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

MRC Innovations, Inc. v. Hunter Mfg., LLP (Fed. Cir. April 2, 2014) 13-1433.Opinion.3-31-2014.1

Panel: Prost (author), Rader, Chen

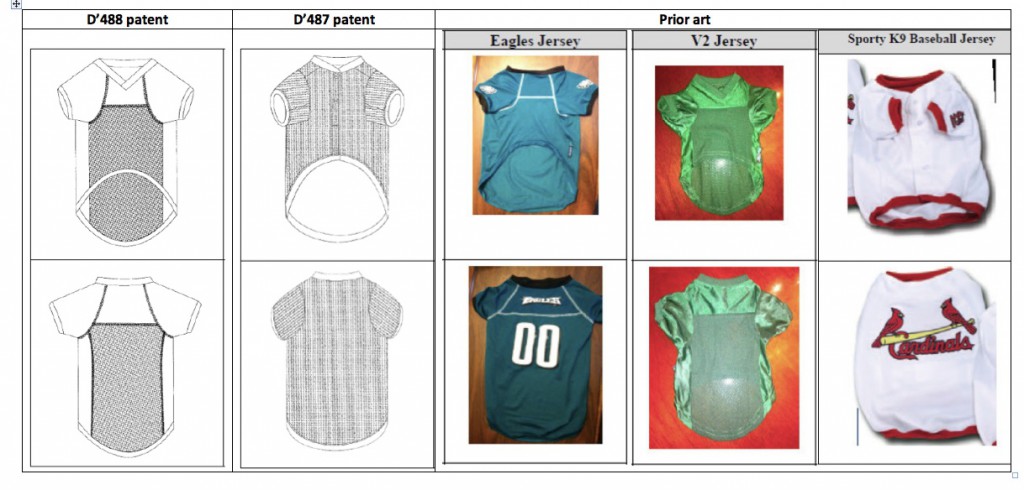

MRC owns U.S. Patent Nos. D634,488 S (“the D’488 patent”) and D634,487 S (“the D’487 patent”). Both patents claim designs for sports jerseys for dogs—specifically, the D’488 patent claims a design for a football jersey (below left) and the D’487 patent claims a design for a baseball jersey (below right):

Mark Cohen is the principal shareholder of MRC and the named inventor on both patents. Hunter is a retailer of licensed sports products, including pet jerseys. In the past, Hunter purchased pet jerseys from companies affiliated with Cohen. The relationship broke down in 2010. Hunter subsequently contracted with another supplier (also a defendant-appellee in this case) to make jerseys similar to those designed by Cohen.

MRC sued Hunter and its new supplier for patent infringement. The district court granted summary judgment to the defendants, concluding that the patents-in-suit were invalid as obvious in light of the following pieces of prior art:

Step One – Primary References

On appeal, MRC argued that the district court erred in identifying the Eagles jersey as a primary reference for the D’488 patent. The Federal Circuit disagreed, stating that either the Eagles Jersey or the V2 jersey could serve as a proper primary reference for the D’488 patent.

MRC also argued that the Sporty K9 jersey could not serve as a proper primary reference for the D’487 patent. Again, the Federal Circuit disagreed, stating that the Sporty K9 jersey had “basically the same” appearance as the patented design.

Step Two – Secondary References

In its analysis, the district court used the V2 jersey and Sporty K9 jersey as secondary references for the D’488 patent and the Eagles jersey and V2 jersey as secondary references for the D’487 patent. On appeal, “MRC argue[d] that the district court erred by failing to explain why a skilled artisan would have chosen to incorporate” features found in the secondary references with those found in the primary references. The Federal Circuit did not agree, stating that:

It is true that “[i]n order for secondary references to be considered, . . . there must be some suggestion in the prior art to modify the basic design with features from the secondary references.” In re Borden, 90 F.3d at 1574. However, we have explained this requirement to mean that “the teachings of prior art designs may be combined only when the designs are ‘so related that the appearance of certain ornamental features in one would suggest the application of those features to the other.’” Id. at 1575 (quoting In re Glavas, 230 F.2d 447, 450 (CCPA 1956)). In other words, it is the mere similarity in appearance that itself provides the suggestion that one should apply certain features to another design.

The Federal Circuit noted that in Borden, it found that designs for dual-chambered containers could be proper secondary references where the claimed design was also directed to a dual-chambered container. And in this case, “the secondary references that the district court relied on were not furniture, or drapes, or dresses, or even human football jerseys; they were football jerseys designed to be worn by dogs.” Accordingly, the Federal Circuit concluded that they were proper secondary references.

Secondary Considerations

MRC also argued that the district court failed to properly consider its evidence of commercial success, copying and acceptance by others. The Federal Circuit disagreed, concluding that MRC had failed to meet its burden of proving a nexus between those secondary considerations and the claimed designs.

Comments

The Federal Circuit hasn’t actually reached the second step of this test in a while. That’s because it has been requiring a very high degree of similarity for primary references (see High Point & Apple I). For a while there, it looked like it was becoming practically impossible to invalidate any design patents under § 103. Now we at least know that it’s still possible.

But we don’t have much guidance as to when it’s possible. In particular, it’s difficult to reconcile the Federal Circuit’s decision on the primary reference issue with its decision in High Point. The Woolrich slipper designs that were used as primary references by the district court in High Point were, at least arguably, as similar to the patented slipper design as the Eagles and Sporty K9 jerseys are to MRC’s designs. But in High Point, the Federal Circuit suggested that there were genuine issues of fact as to whether the slippers were proper primary references.

And unfortunately, the Federal Circuit seems to have revived the ill-advised Borden standard. As I’ve argued before, the second step of the § 103 test has never made much sense. Even the judges of the C.C.P.A., the court that created the test, had trouble agreeing about how it should be applied. But the Borden gloss—that there is an “implicit suggestion to combine” where the two design features that were missing from the primary reference could be found in similar products—is particularly nonsensical. At best, this Borden-type evidence suggests that it would be possible to incorporate a given feature into a new design, from a mechanical perspective—not that it would be obvious to do so, from an aesthetic perspective.

All in all, this case provides an excellent illustration of the problems with the Federal Circuit’s current test for design patent nonobviousness. Perhaps now that litigants can see that § 103 challenges are not futile, the Federal Circuit will have opportunities to reconsider its approach.

anon,

I have no idea what you’re talking about, I am not “leaning on law that never was”. The first three sentences in the first paragraph of my original comments are merely setting out the historical background of section 103 and how the framers of the 1952 Patent Act did not consider how this section might effect designs. If you read the concurring opinion of Judge Rich in the Nalbandian decision maybe you’ll learn something.

The content of the second paragraph of my original comments is based on the interpretation of section 103 by the CAFC and its predecessor court the CCPA. First, the reference to “one of ordinary skill in the art” in section 103 has been determined to be a “designer of ordinary skill in the art” in the Nalbandian decision. Second, that a primary reference must have “an overall appearance basically the same as the claimed design” is set forth in the decision of In re Rosen and further qualified in the decision of In re Harvey. Third, that secondary references must be “…so related that the appearance of certain ornamental features in one would suggest the application of those features to the other.” is set forth in the decision of In re Glavas.

Tell me where in my original comments you think I’m not relying on current law as interpreted by the CAFC.

What you apparently what me “to learn” is that you are applying wishful thinking as if it actually made it through the process and became law.

Short of that change – and given the law that I have supplied to you – the onus is on you to somehow show that what I supplied is not – in fact – what the law actually is here and now.

Read my posts at 9.2 and 9.2.1 and tell me the law.

I don’t know what law you supposedly gave me. What I gave you is the law for design patents according to the CAFC, if you choose to ignore it and want it to be something else good luck with that. As Perry said, even in retirement, I have more important things to spend my time on.

As a final thought, you can talk the talk, I’ve walked the walk and applied the law as it is set out by the CAFC thousands of times over. How many 103 rejections in design patent applications have you given? I think I know the answer – 0.

By the way, that must be some good suff your smoking.

“I don’t know what law you supposedly gave me”

(sigh) – once again see my posts at 9.2 and 9.2.1

You should be aware that the CAFC does not write the law either – what they have in the decisions you reference is the interpretation of the law. I provided you the source of the law. It is that law that my question is directed to. I certainly hope that in all of your walking that you paid attention to the law that the court itself cites for the authority in its decisions.

What do you want me to tell you about section 171, it provides for design patents and is the basis for rejections for lacking in ornamentality and originality, it has nothing to do with obviousness. Do you have the ability to be coherent at all.

Coherence? You need to check yourself and the law again my friend. It tells you that the patent act (in the section under discussion) applies.

Don’t tell me you walked your entire career without realizing the actual basis of law.

To my friend, Perry Saidman, I concur with you on all points addressed. Anyone familiar with the history of section 103 knows that it was not intended to be applied to designs for very long. The drafters of the 1952 Patent Act intended to move designs out from under the patent statute and into copyright law as a registration. As Judge Rich said in his concurring opinion in In re Nalbandian “… the new section 103 which was written with an eye to the kinds of inventions encompassed by section 101 with no thought at all of how it might affect designs.” And you wonder why the courts, including the CAFC, struggle with the application of obviousness in design patent cases? This quote from Judge Rich can also be applied to the Supreme Court in their decision of KSR. Do you really think the justices thought at all of how this decision might affect designs? To the best of my knowledge the Supreme Court has not heard a design patent case in over 100 years. I doubt seriously that any of the current justices have much knowledge about design patent practice.

The conundrum with applying section 103 to design patents is in the determination of who is “one of ordinary skill in the art”. While a “designer of ordinary skill in the art” may not actually exist in reality, I know of no better standard to apply given the context of the language in section 103. It’s certainly better than the “ordinary observer”. In addition, since patentability of an ornamental design is based on its overall appearance it makes perfect sense that to establish lack of patentability of an ornamental design under 35 U.S.C. 103 a primary reference must be analogous and have an overall appearance basically the same as the claimed design, and any secondary references relied on must be analogous and have a visual relationship to the primary refcerence in order for there to be a motivation to combine. If a primary reference and secondary references have no visual relationship there can be no logical basis to combine them to show lack of patentability from an appearance standpoint.

As a retired design patent examiner I consider the three references in the MRC case to establish a sound basis to invalidate the two design patents as being obvious under 35 U.S.C. 103. The only significant visual difference between the two patented designs and the three prior art references is the serge stitching down the back of the ‘488 design patent. However, I would not consider this difference to create a sufficient visual distinction over the three prior art references as combinded to justify patentability from an ornamental design standpoint.

While I agree in the real world designers may look to diverse arts for inspiration, in the world of patent law under section 103 it’s impractical to permit references directed to diverse subject matter to be combined to establish lack of patentability. To do so would take us back to pre-Glavas and pre-Rosen type piecemeal rejections. That would not be progress.

I do agree, and I can tell you from my 40+ years of experience in the design patent field, that the window for rejecting a design patent claim under section 103 has narrowed significantly. However, it is nice to know that every once in awhile the CAFC will affirm that rejections under section 103 of the statute in design patent cases are alive and well.

Jim,

Perhaps you will pick up the question that others have run from.

Perhaps you can explain this “it was not intended to be applied to designs for very long” – do you have some recognized authority (i.e. Congress) that you can rely on?

I look forward to answer that would do your 40+ years experience proud.

anon,

As I stated in the second sentence of my previuos comment, the framers of the 1952 Patent Act intended to move designs out from under the patent statute and place it under copyright law as a registration. It was called the Willis Bill H.R. 8873, (a copy of which I have), and was introduced in the 85th Congress in 1957. It was introduced almost continuosly in succeding sessions of Congress for approximately 25 years. As a design patent examiner I lived under this cloud for approximately the first 12 years of my career. If you read the concurring opinion of Judge Rich in the Nalbandian decision he lays out very clearly how the framers of the 1952 Patent Act intended to deal with the “design problem”.

Thanks Jim for the solid post.

I will check into this attempt.

Any thoughts as to why this attempt did not succeed? Why Congress did not feel that the views expressed in the attempt actually merited being made into actual law?

Finally, short of this actually being made into law, what possible foundation (in law) do you have to hang your hat on?

Surely you recognize that a mere bill will not – and cannot – suffice for the proposition that you want to advance as controlling law, right? Surely, you recognize that something more is required, right?

Please tell me what you understand this something more to be.

anon,

My understanding about why this bill never past is because there was no support for it from the patent bar. However, I know the USPTO was in favor of the bill.

As for your other question, I’m not clear about what you want me to qualify regarding controlling law?

What I want you to qualify is how you expect anyone to form an opinion of what the existing law means by merely leaning on law that never was.

Even if the views expressed in the bills were a desired thing, that thing never came into legal existence and the law – today – here – and now – must be construed according to what is real and not what merely amounts to fanciful wishful thinking that never came to pass.

Yes, I know a startling concept that understanding what the law is is to be based on what was actually made into law…

For the record, I’ll note that I appear to agree with Perry about the non-“nonsensical” logic of the Borders decision (with caveats noted elswhere). But then Perry made this strange statement:

As one example, you simply cannot find a teaching, suggestion or motivation for combining design features because there are no words (save for figure descriptions) in a design patent.

Without getting into the silliness (and I agree with Perry that silliness abounds) of the blanket unquestioning application of utility patent concepts/law (e.g., KSR) to design patents, I disagree with Perry’s statement above. Prior art for design patents is not limited to prior design patents. The number of non-patent publications describing ornamentation and design and why various designs appeal (or don’t) to human beings (or, I suppose, other animals) is enormous. Some of these publications are certainly relevant to determining the “obviousness” of most (if not all) designs.

Pray tell you will answer the question then as to the source of the design patent law if not linked to the statute….

(for all its silliness, where else are you going to look?)

B-b-b-but Malcolm always supports his views and conclusions…

/eyeroll

btw, this might help you start your search for an answer:

35 U.S.C. 171 Patents for designs.

Whoever invents any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.

The provisions of this title relating to patents for inventions shall apply to patents for designs, except as otherwise provided.

Please provide something that at least imitates a signal rather than the usual copious noise that you clang with.

This too may help:

from link to law.cornell.edu

Historical and Revision Notes

Based on Title 35, U.S.C., 1946 ed., § 73 (R.S. 4929, amended (1) May 9, 1902, ch. 783, 32 Stat. 193, (2) Aug. 5, 1939, ch. 450, § 1,53 Stat. 1212; R.S. 4933).

The list of conditions specified in the corresponding section of existing statute is omitted as unnecessary in view of the general inclusion of all conditions applying to other patents. Language is changed. (emphasis added)

…and by the way, these helpful tidbits I provide – these are something called ‘signal,’ in case you are unaware of it.

these helpful tidbits I provide – these are something called ‘signal,’

Patent Jeebus has spoken!

Bow down, everybody.

LOL – I even spot you the law and its historical context, and all you can do is reply with empty ad hominem insults.

It’s hilarious that you are so unaware of the impression you are creating for yourself Malcolm.

The silence to the basics I provide screams volumes.

Right back atcha 4.1.1.2.1.1 –

Dazzle is not claimed in the ‘488, but mesh and interlock are, creating more distance from the V2.

As for the raglan sleeves, well, that’s a fundamental difference of construction of a garment with both aesthetic and functional effects, further distancing V2 as a secondary reference.

But. Looking at my real (numbers-sewn-on) Eagles #87 jersey, it’s identical to the ‘488, except the mesh is on the sides (otherwise the heavy sewn-on-numbers would tear the fabric). In light of this example, the ‘488 is obvious, and it’s the first place I’d look to destroy the patent. That’s why I’m going to proudly wear it on Monday, with bodyguard.

As for stopping the flattering infringement of my patent, I can do that myself, thank you very much!

Let us quibble no further about exactly where the mesh fabric is and exactly where the interlock fabric is and whether there’s any other fabric – all silly 112 issues….

Now Patent & Eagles destruction! DeSean would like that…

I am digging deep for Eugene, but do you mean McEnroe? I didn’t know they had tennis courts in Toledo…

(p.s. Thank you, Flann, for opening the humor door with your jersey-under-suit confession…)

Anytime! 🙂

“Perhaps now that litigants can see that § 103 challenges are not futile, the Federal Circuit will have opportunities to reconsider its approach.”

I wonder if we would see the Ned Heller umbrage factor if the Federal Circuit reconsidered its approach to § 103 challenges and re-evaluated exactly what the Supreme Court is limited to do by the 1952 Act which stripped law writing from the Court’s toolbox.**

Can you imagine if Chief Judge Rader would be able to convince his fellow judges that KSR cannot be good law to the extent that it warps the words explicitly used by Congress?

Ned would have a serious meltdown.

** – reminds me of the adage: be careful what you wish for, as you just might get it.

BTW, one prior rationale for making it harder to invalidate design patents under 103 was prior CAFC statements about how narrow design patent claims are.

But is that really consistent with current “Egyptian” infringement decisions [and inherent broad claim scope interpretations] by “ordinary observers” (lay jurors)?

Furthermore, there have been CAFC decisions in which 103 rejections have been upheld of utility patents with very narrow claims, aka “picture” claims, by combining features of plural references, where their combination was unobvious to one one ordinary skill in the art. I.e., narrow claiming does not directly correlate to unobviousness.

Paul,

Your comment here at 4 also feeds into my response at 3.1.2.

It’s harder to invalidate design patents under 103 than have them infringed because the former is seen through the eyes of a skilled designer to whom more things will be obvious than to an ordinary observer to whom more things will appear substantially the same. So, the two tests are consistent.

I agree that there is anecdotal evidence of a lot of things, but clearly, in general, it is easier to invalidate a broad claim than a narrow claim.

I am presenting this case Monday afternoon to the examiners, so I’m glad it was just decided. The phrase “too high a level of abstraction” comes to mind. In light of Apple, the outcome surprises me.

From the perspective of one who is “skilled in the art,” this case sets a very high bar. Cohen combined different prior elements to make the perfect design that Hunter recognized and exploited (my dogs wear Hunter jerseys, wish I had known), but which no one else had done previously. Judges may need to create a framework of primary and secondary references, but designers don’t work that way – the process is more fluid and intuitive.

Perhaps that’s why I share Sarah’s view about this case – we both have design backgrounds. I picked up on the “why” and “when” questions in Sarah’s writings on obviousness, because they are important ones.

Regardless of whether it was “perfect”, it was too close to MRC’s own prior art, which

BTW they failed to disclose to the examiner (wish they had known). MRC had ample opportunity to prove its design was “perfect” (secondary considerations) and failed to do so.

In fact, I got the impression from the language of the DCT opinion that the court was punishing MRC for not revealing the prior art (yes, MRC’s bad). But that should not allow for a possibly biased analysis under a summary judgment standard. There was no disputed fact that the references existed, but whether it was obvious to combine them needed more reasoning. The ‘488 made changes of over 50% to the prior art.

I look forward to hearing the examiners’ perspectives on Monday.

I designed an umbrella whereby I flipped the canopy, such that the serge stitching that’s normally underneath was now a design feature. Zillions of umbrellas existed in the prior art that used serge stitching to connect 8 fabric panels – I simply reversed the fabric. I would have lost a §103 on SJ on these grounds, but I assure non-designers that this was not an obvious thing to do – some people found it a “shocking” premise.

Needless to say, it was not a best-seller, but was considered a “novel” idea by buyers and manufacturers.

“novel” idea…

…or a “nonobvious” idea?

You can’t use a design patent to protect an idea, only a specific embodiment of that idea. Think copyright law.

Perry,

I presumed that Flann was discussing something protect-able and was merely being colloquial with his use of ‘idea.’

Right tree, wrong forest.

Anonymous (who ARE you?),

They won’t let me create 4.1.1.1.1.1.1, so I’ll have to respond this way:

Right idea, wrong gender.

…gender?

I’ll let Flann answer that herself…

lol – that was really a nit that you are searching out Perry (apologies to Miss Flan).

Look at the ‘488 patent. Look at the V2 jersey. They are identical, but for the claimed surge stitching along the seams – a feature taught by the Eagles jersey, save for one seam in the back. This is not even close to 50%. And the Eagles jersey is almost identical to the ‘488 but for a few very minor aesthetic features taught by the V2 (e.g., the collar).

This is not the same as making previously invisible serge stitching visible; if you were the first to make serge stitching visible on the outside of an umbrella, that’s likely design patentable. I’m shocked you didn’t get one!

Thanks anon- I meant both.

V2:

Differences: dropped sleeves, dazzle fabric, no serge stitching at all (3)

Similarities: v-neck, mesh top and bottom panels. (2-3)

Eagles:

Differences: 100% mesh body, crew neck, no serge stitching down back. (3)

Similarities: shoulder serge stitching, raglan sleeves, materials. (3)

I measured: about 40% surface area change plus addition of 16″ of surge stitching to about 30″. (Designers don’t necessarily think that way, but infringers do).

I still think it’s too close a call for a judge to make on SJ. (Haven’t you used a 75-80% similarity standard for obviousness? Should references be added up, or applied singly?) Again, just because the references are there doesn’t mean it would be obvious for a phosita to combine them. But Hunter could very well have won a full trial too on the facts.

I patented the only design (out of many) I sensed would be commercially successful enough to merit patenting. The patent expires in 7 months, and it’s still being knocked off.

I’m wearing my Eagles jersey under my suit on Monday, being a Philly chick.

I’m dazzled by your list of differences and similarities, which qualifies you, prima facie, to be a district court judge! Please point out where “dazzle fabric” is mentioned in the ‘488, and let me know how it looks different? Dropped sleeves, really? Honestly, I see no difference in the sleeves. Serge stitching, that’s the only difference. If I still had the samples, I’d bring them to the PTO Monday afternoon so you can see them in person.

BTW, if you need a lawyer to chase the infringers of your patent, I can recommend a great design lawyer in PA. In fact, he’ll be at Design Day. And I suggest you wear the Eagles jersey over your suit, despite your embarrassment at revealing you’re a Philly fan.

With all due respect to my friend Professor Burstein, a careful reading of High Point suggests that the Federal Circuit reversed not because it thought that Woolrich was an improper primary reference, but because the district court utterly failed to characterize the claimed design in a way that would have enabled the Fed. Cir. to properly review the case on appeal, violating step one of Durling. And the Court’s secondary reference discussion in MRC was hardly nonsensical – it clarified what the Glavas “so related” test means, which is that the features of a dog jersey can be combined with the features of a dog jersey when the claimed design is a dog jersey. You don’t have to show anything else. The message is that if the secondary reference had been a piece of furniture, you’d best settle the case.

That both references would have to be for the same product to be combinable for a 103 rejection is inconsistent with the Sup. Ct. KSR decision.

It is also inconsistent with 103 itself, from “..obvious .. to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which said subject matter pertains.” In the case of design patents, that “person” in that “art” [“ornamental design”] is a product designer, and obviously no product designer ever made a living solely specializing in designing dog blankets! Industrial design experts work on improving product appearances in a wide variety of products.

Perhaps I was not clear as I could have been – “same product” is of course too narrow. The test for combinability of two designs is whether the underlying articles of manufacture are “related”. In MRC, they were not only related, they were identical. It’s pretty clear that a designer of ordinary skill of pet football jerseys would not look to the designs of drapes, dresses or furniture for inspiration.

“It’s pretty clear that a designer of ordinary skill of pet football jerseys would not look to the designs of drapes, dresses or furniture for inspiration.”

Ah, Perry, but this is not what KSR says.

KSR says that the solution itself may very well allow such inspiration from such disparate fields to be considered to be obvious.

That leading edge of the sword of KSR has been made very powerful indeed.

(and of course, we should not forget that that very powerful sword is a double-edged sword, and that patent applicants need not include in their applications a fair degree of what the leading edge sweeps in.

Even this topic segues into the greatest issue in patent law today.

As any astute mind then can connect the dots, the Court (again) is revealed as the source of much of today’s QQ, as this expansion of power given to 103 has the (unintended) consequence of broadening the admissibility of functional claiming (i.e. claims with structure and functional elements).

If one takes an objective viewpoint of what the Court created and note that “in the art to which the claimed [software or computer implemented] invention pertains” allows for a person of ordinary skill in that particular art (and to whose shoes someone must stand in to judge a claim) to accept functional claim elements (brushing aside the smokescreen and strawman of anything ‘totally in the mind’).

Supreme Court: we reap what you sow. Do not blame the scriviners for using what you provide.

Interesting that this design patent case has sparked such a heated discussion about KSR, which, need I say it, is a utility patent case with utility patent language and utility patent logic. As far as I know, no case has been decided applying KSR to design patent obviousness analysis – and for good reason. I’ll let the astute minds connect the dots on this one…

Perry,

Isn’t there a (rather large) bone of contention when it comes to design patent law – specifically, that design patent law is required to follow the statutory basis of utility patent law, and that (implicit in your comment at 3.1.1.1.1) ‘special treatment’ for design patents (e.g. treating them like trademarks) is something like connecting dots that an astute mind should be aware of not doing?

In other words, isn’t trying to treat design patents ‘special’ (different regimes of obviousness and novelty) to be frowned upon?

It’s not special treatment, silly, it’s different treatment. As one example, you simply cannot find a teaching, suggestion or motivation for combining design features because there are no words (save for figure descriptions) in a design patent. This is one reason why KSR and similar utility patent analyses are inapplicable to design patents, and why the Federal Circuit, time and time again, has affirmed the Rosen/Durling “primary reference” test and Glavas “secondary reference” test for design patent obviousness analysis. It works.

Here’s something to do for anonymous astute minds who have some spare time: how would KSR apply to the MRC facts? What is the test? What would be the analysis? What would be the result? Is it better/worse than Rosen/Glavas?

“It’s not special treatment, silly, it’s different treatment.”

BZZZT – wrong. Different but the same statutory text applies. The only way you get to different from the same starting point is special treatment. Your word play is rejected.

“you simply cannot find a teaching, suggestion or motivation for combining design features because there are no words (save for figure descriptions) in a design patent”

BZZZT – wrong. Who said anything about teaching, suggestion or motivation must come only from words?

Whether “it works” or not is a non sequitur to the fact that special (i.e. different) evaluation/enforcement mechanisms are in play stemming from the same statute. The point is NOT that different works – the point is why is there a difference in the first place? You are ASSuming both that there must be a difference and that such difference is sub silentio acceptable. You have jumped to a conclusion that I am asking you to sustain in the first instance.

Before you have me chasing your astute task, please finish the one already before you.

Oh, here we go again. Why don’t you rewrite you post pretending that I know who you are? Better yet, who are you? Reveal thyself, knave.

or better yet, why don’t you address the legal points before you and not be so concerned over the identity of the person placing those points before you?

Cat your your tongue as to any real answers? So much so that you dive headfirst into a “who are you?” gambit?

So predictably disappointing from the self-anointed wizard of design patent law. I was hoping that your visit to these boards this time saw some actual answers from you.

Your post, anon, is sufficient evidence for me to bow out of this “discussion”. I suggest you change your moniker to “adhominem” – although it’s not registrable as being merely descriptive, it’s more apt.

And your moniker could be “any port in a storm” as once again, you flee at the merest ruffling of feathers.

But please, pretend that you are fleeing for some other ‘noble’ reason than you really don’t have an answer to the ‘special treatment’ question placed before you.

Don’t worry. Next time you show up to trumpet your great command of design patent law, real questions of law will be ready to greet you. Shame then, that you see only ad hominem when you first ran from the law and it was only the ad hominem mocking you as you ran away that you are fixated upon.

Exhibit A, redux. I have more answers than you possibly have questions for. Why should I waste my time with those who hide behind the cloak of anonymity? There are simply more important fish to fry.

You may now post your clever, mocking retort, to which you will get no reply.

You wish to play again with your folly, and the legal question remains on the table.

It still awaits you (and yes, regardless of my identity).

I seek not a reply to my mocking retort (for which, you do not have the wit), but please sir, show your so-called design patent knowledge.

If you dare.

More 103 and anti-Judicial wax addiction fodder:

As listed at link to law.cornell.edu

The historical note to 103 states “This paragraph is added with the view that an explicit statement in the statute may have some stabilizing effect, and also to serve as a basis for the addition at a later time of some criteria which may be worked out.”

The stabilizing effect noted is in direct relation to the Court and its mashing of the 101 nose of wax.

The addition at a later time is NOT the courts making common law evolution. It would make no sense to remove that tool from the Court because of its addition to nose of wax mashing and give that right back to the Court. This note can only mean that any such later worked out criteria would come from additional explicit words from Congress, the branch of the government (the only branch) allocated the authority to write patent law.

Reading the map is clearly different from writing the map.

Re: “Reading the map [103] is clearly different from writing the map.”

True, and since none of us have any influence at all on either, any personal opinions that judicial decisions have been wrongly decided are a waste of time and useless for any counseling UNLESS there is a REALISTIC chance that those decisions may not survive en banc or Supreme Court scrutiny by the time the same issues come up again. Many Fed. Cir. decisions have not survived Sup. Ct. appeals in recent years, and even more will not in 2014. Note the statistics in the next blog, immediately above.

To Paul’s comment of “since none of us have any influence at all on either,… waste of time and useless… UNLESS there is a REALISTIC chance…,” I have found my historic quote that I wanted to offer up in reply. It brings to mind the exemplary nature of a man willing to live (and die) by his convictions, and not to weigh the correctness of a course of action by some view of its current possibility of success:

“It is the First responsibility of every citizen to question authority.”

~ Ben Franklin.

“That both references would have to be for the same product to be combinable for a 103 rejection is inconsistent with the Sup. Ct. KSR decision.”

Perhaps the flaw is in the Supreme Court decision? (and your reasoning that flows from that only exacerbates that flaw)

After all, the explicit words used by Congress in 103 are: “to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains”

Expanding what is to be considered legally obvious by expanding the particular world of potential prior art to be anything other than in the art to which the claimed invention pertains is a pernicious form of judicial activism, eh?

Your very notion of expanding beyond one product type is itself inconsistent with the words of 103.

Patent law does not promote innovation if a traditional font of innovation is denied even the chance to obtain a patent.

It is the direct opposite of your view Paul that makes the most sense for the words that Congress explicitly chose.

Is it any surprise that the Supreme Court’s nose of wax addiction follows into the jurisprudence of 103?

Jason the Borden gloss—that there is an “implicit suggestion to combine” where the two design features that were missing from the primary reference could be found in similar products—is particularly nonsensical. At best, this Borden-type evidence suggests that it would be possible to incorporate a given feature into a new design, from a mechanical perspective—not that it would be obvious to do so, from an aesthetic perspective.

There’s nothing “nonsensical” about this. A prior art cup has flower ornamentation. What’s “nonsensical” about using that cup to show the obviousness of a mug (i.e., a cup with a handle) with flower ornamentation on it?

The only aspect of the Borden test that is “nonsensical” is that it is too limited. The obviousness of a design shouldn’t be predicated on the similarity between a first reference and second reference. All that’s needed is a showing that the design “feature” in question is one that was (1) deemed to be aesthetically pleasing in the prior art and (2) understood to be aesthetically pleasing in different contexts. At that point the burden should be on the applicant/patentee to prove “teaching away” from the obvious design.

What was the feature at issue in this case, anyway?

For a while there, it looked like it was becoming practically impossible to invalidate any design patents under § 103.

Hence the excitement of Kappos over this wonderful new playground for trolling. Oh, what fun it’s going to be! U.S. design patent law is just a terrible joke that isn’t going to get any better anytime soon.

Your obsession with (any) patent existing for trolling is more than a bit odd.

The really interesting question is how can the CAFC continue to justify this very different and limiting obviousness test for design patents, versus other [utility] patents, when its 103 statutory base is identical for both? [Is this test a candidate for yet another unanimous Sup. Ct. reversal of the CAFC, at the rate at which they are now taking cert on CAFC decisions, by a future losing defendant?]

Furthermore, the other prior attempts by some CAFC panels in In re Lee, 277 F.3d 1338 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (and some other CAFC panel decisions cited therein) to impose this same added obviousness test requirement of a specific teaching or suggestion in the art [one reference] for combining that reference with other references was clearly not supported in the subsequent Supreme Court decision in KSR v. Teleflex.