by Dennis Crouch

Fox Factory, Inc. v. SRAM LLC (Fed. Cir. 2019)

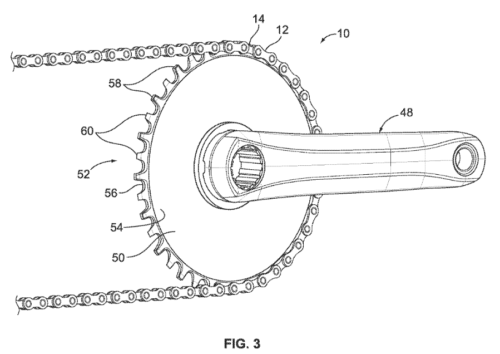

This is an important case for anyone arguing secondary indicia -- not a good case for patent holders. The court here again raised the "nexus" hurdle by holding that a presumption of nexus can only be achieved by proving that the product being sold by the patentee is "essentially the claimed invention." This is a situation where SRAM owned two patents in the same patent family -- both of which covered aspects of its X-Sync bicycle chainring (gear). Each patent included elements not claimed in the other -- for the court that was enough evidence to disprove coexistence.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.