All posts by Jason Rantanen

CBT Flint v. Return Path: Applying 28 U.S.C. 1920(4) to E-Discovery Costs

Ohio Willow Wood v. Alps South

Guest Post by Prof. Risch: Functionality and Graphical User Interface Design Patents

Guest Post – PAEs under the Microscope: An Empirical Investigation of Patent Holders as Litigants

Disuniformity

Summary of Oral Argument in Medtronic v. Boston Scientific by Prof. La Belle

Intellect Wireless v. HTC

Samsung Proposes a Patent Pledge to Settle EC FRAND Investigation

PTO Post-Issuance Filings

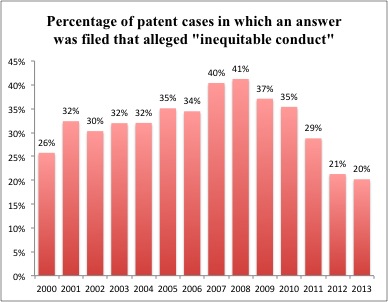

Trends in Inequitable Conduct

Oral Argument Recap: Lighting Ballast Control v. Philips

High Point v. Buyer’s Direct – Tell me more, tell me more (about design patents and § 103)

Guest Post By Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

High Point Design LLC v. Buyer’s Direct, Inc. (Fed. Cir. Sept. 11, 2013) Download High Point v Buyers Direct

Panel: Schall (author), O’Malley, Wallach

High Point Design LLC (“High Point”) and Buyer’s Direct, Inc. (“BDI”) both manufacture fuzzy slipper-socks. In this case, BDI accused High Point of infringing U.S. Des. Patent No. D598,183 (the “D’183 patent”). In May, the district court granted summary judgment in favor of High Point, concluding that the patented design was invalid as obvious and as functional. It also dismissed BDI’s trade dress claim.

The most interesting parts of this decision deal with the issue of obviousness. In the design patent context, the § 103 analysis has two steps. First, the court must identify a proper primary reference—i.e., a “something in existence” that has “basically the same” appearance as the claimed design. Second, other references can be used (assuming certain conditions are met) to modify the primary reference “to create a design that has the same overall visual appearance of the claimed design.”

In High Point, the district court identified two Woolrich slippers, the “Penta” and the “Laurel Hill,” as primary references. In particular, the district court found that the Penta slipper “looks indistinguishable” from the claimed design and that the Laurel Hill slipper had some “insubstantial” differences but “nonetheless has the precise look that an ordinary observer would think of as a physical embodiment” of the claimed design. The district court did not, however, include any images of these designs. For your reference, however, here is a chart comparing the Penta slipper to some of the drawings from the D’183 patent:

On appeal, the Federal Circuit decided that the district court erred in its primary reference analysis in a number of ways. According to the Federal Circuit, the district court “erred by failing to translate the design . . . into a verbal description.” On this point, the court relied on its 1996 decision in Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., Inc. In Durling, the court divided the first step of the § 103 analysis (i.e., the determination of whether there is a proper primary reference) into two parts, instructing district courts to: “(1) discern the correct visual impression created by the patented design as a whole; and (2) determine whether there is a single reference that creates ‘basically the same’ visual impression.” According to the Federal Circuit, the district court’s analysis in High Point failed to satisfy both of these requirements.

As to the “first part of the first step”—i.e., “discern[ing] the correct visual impression”—the Federal Circuit noted that, under Durling, “the trial court must first translate [the design patent’s] visual descriptions into words,” so that “the parties and appellate courts can discern the internal reasoning employed by the trial court to reach its decision as to whether or not a prior art design is basically the same as the claimed design.”[1] The Federal Circuit found the district court’s description of the D’183 patent to be insufficient because it described the claimed design at “too high a level of abstraction.” So it reversed and remanded on the issue of obviousness, instructing the district court to “add sufficient detail to its verbal description of the claimed design to evoke a visual image consonant with that design.” The Federal Circuit did not, however, explain how much detail would be “sufficient” to meet this evocation standard.

This part of the opinion may seem strange in light of the 2008 en banc decision in Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., in which the Federal Circuit cautioned district courts against “attempt[ing] to ‘construe’ a design patent claim by providing a detailed verbal description of the claimed design.” In Egyptian Goddess, the Federal Circuit did attempt to distinguish Durling, stating in a footnote that “[r]equiring such an explanation of a legal ruling as to invalidity is quite different from requiring an elaborate verbal claim construction to guide the finder of fact in conducting the infringement inquiry.” Whether that distinction is persuasive is an issue for another day.

As to the second part—i.e., determining whether there is a reference with “basically the same” impression—the Federal Circuit concluded that the district court failed to adequately explain its reasoning. It stated that, on remand, “the district court should do a side-by-side comparison of the [potential primary reference and the claimed design] to determine if they create the same visual impression.”

The Federal Circuit identified a number of other errors in the district court’s § 103 analysis, including its use of an “ordinary observer” standard. The Federal Circuit reiterated that “the obviousness of a design patent must . . . be assessed from the viewpoint of an ordinary designer,” notwithstanding some unfortunate dicta (my characterization, not the court’s) in the 2009 case of Seaway Trading Corp. v. Walgreens Corp.

However, despite all of its criticisms of the district court’s analysis, the Federal Circuit did not say that the district court’s conclusion was wrong. Indeed, the Federal Circuit expressly refused to take a position on the ultimate issue of whether the D’183 patent was obvious. And the Federal Circuit did not say that the Penta or the Laurel Hill slippers could not qualify as primary references. So it will be very interesting to see what happens on remand.