All posts by Jason Rantanen

PatCon 4: The Patent Troll Debate

Design patent nonobviousness jurisprudence — going to the dogs?

Guest post by Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

MRC Innovations, Inc. v. Hunter Mfg., LLP (Fed. Cir. April 2, 2014) 13-1433.Opinion.3-31-2014.1

Panel: Prost (author), Rader, Chen

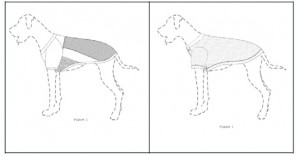

MRC owns U.S. Patent Nos. D634,488 S (“the D’488 patent”) and D634,487 S (“the D’487 patent”). Both patents claim designs for sports jerseys for dogs—specifically, the D’488 patent claims a design for a football jersey (below left) and the D’487 patent claims a design for a baseball jersey (below right):

Mark Cohen is the principal shareholder of MRC and the named inventor on both patents. Hunter is a retailer of licensed sports products, including pet jerseys. In the past, Hunter purchased pet jerseys from companies affiliated with Cohen. The relationship broke down in 2010. Hunter subsequently contracted with another supplier (also a defendant-appellee in this case) to make jerseys similar to those designed by Cohen.

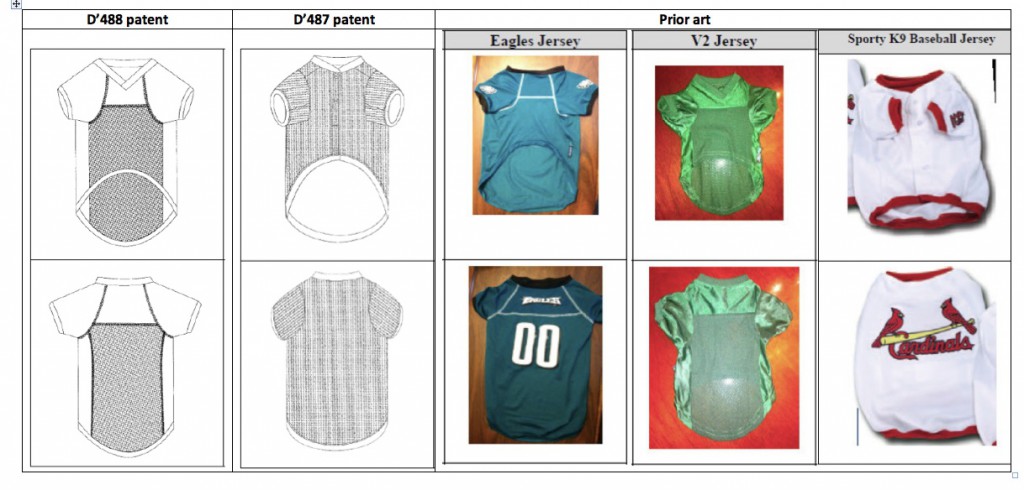

MRC sued Hunter and its new supplier for patent infringement. The district court granted summary judgment to the defendants, concluding that the patents-in-suit were invalid as obvious in light of the following pieces of prior art:

Step One – Primary References

On appeal, MRC argued that the district court erred in identifying the Eagles jersey as a primary reference for the D’488 patent. The Federal Circuit disagreed, stating that either the Eagles Jersey or the V2 jersey could serve as a proper primary reference for the D’488 patent.

MRC also argued that the Sporty K9 jersey could not serve as a proper primary reference for the D’487 patent. Again, the Federal Circuit disagreed, stating that the Sporty K9 jersey had “basically the same” appearance as the patented design.

Step Two – Secondary References

In its analysis, the district court used the V2 jersey and Sporty K9 jersey as secondary references for the D’488 patent and the Eagles jersey and V2 jersey as secondary references for the D’487 patent. On appeal, “MRC argue[d] that the district court erred by failing to explain why a skilled artisan would have chosen to incorporate” features found in the secondary references with those found in the primary references. The Federal Circuit did not agree, stating that:

It is true that “[i]n order for secondary references to be considered, . . . there must be some suggestion in the prior art to modify the basic design with features from the secondary references.” In re Borden, 90 F.3d at 1574. However, we have explained this requirement to mean that “the teachings of prior art designs may be combined only when the designs are ‘so related that the appearance of certain ornamental features in one would suggest the application of those features to the other.’” Id. at 1575 (quoting In re Glavas, 230 F.2d 447, 450 (CCPA 1956)). In other words, it is the mere similarity in appearance that itself provides the suggestion that one should apply certain features to another design.

The Federal Circuit noted that in Borden, it found that designs for dual-chambered containers could be proper secondary references where the claimed design was also directed to a dual-chambered container. And in this case, “the secondary references that the district court relied on were not furniture, or drapes, or dresses, or even human football jerseys; they were football jerseys designed to be worn by dogs.” Accordingly, the Federal Circuit concluded that they were proper secondary references.

Secondary Considerations

MRC also argued that the district court failed to properly consider its evidence of commercial success, copying and acceptance by others. The Federal Circuit disagreed, concluding that MRC had failed to meet its burden of proving a nexus between those secondary considerations and the claimed designs.

Comments

The Federal Circuit hasn’t actually reached the second step of this test in a while. That’s because it has been requiring a very high degree of similarity for primary references (see High Point & Apple I). For a while there, it looked like it was becoming practically impossible to invalidate any design patents under § 103. Now we at least know that it’s still possible.

But we don’t have much guidance as to when it’s possible. In particular, it’s difficult to reconcile the Federal Circuit’s decision on the primary reference issue with its decision in High Point. The Woolrich slipper designs that were used as primary references by the district court in High Point were, at least arguably, as similar to the patented slipper design as the Eagles and Sporty K9 jerseys are to MRC’s designs. But in High Point, the Federal Circuit suggested that there were genuine issues of fact as to whether the slippers were proper primary references.

And unfortunately, the Federal Circuit seems to have revived the ill-advised Borden standard. As I’ve argued before, the second step of the § 103 test has never made much sense. Even the judges of the C.C.P.A., the court that created the test, had trouble agreeing about how it should be applied. But the Borden gloss—that there is an “implicit suggestion to combine” where the two design features that were missing from the primary reference could be found in similar products—is particularly nonsensical. At best, this Borden-type evidence suggests that it would be possible to incorporate a given feature into a new design, from a mechanical perspective—not that it would be obvious to do so, from an aesthetic perspective.

All in all, this case provides an excellent illustration of the problems with the Federal Circuit’s current test for design patent nonobviousness. Perhaps now that litigants can see that § 103 challenges are not futile, the Federal Circuit will have opportunities to reconsider its approach.

Guest Post by Prof. La Belle: Demand Letters, DJ Actions, and Personal Jurisdiction

Supreme Court to Address Standard of Review for Claim Construction

The meaning of “intellectual property”

Bose v. SDI: Post-verdict intent

PatCon 4

Guest Post: Patent Remedies Should Not Depend on a Patentholder’s Business Model

Footnote 11 in Pfaff

Danisco v. Novozymes: DJ’s and pre-issuance activity

Two Upcoming Conferences

Ring & Pinion v. ARB: No Foreseeability Limitation on DOE

Dissenting over Internal Procedures at the Federal Circuit

Sedona Conference Webinar – Patent Litigation Best Practices

Nazomi v. Nokia

Acquired Patent Licensing: Guest Post by Prof. Risch

Guest Post on Pacific Coast Marine by Prof. Sarah Burstein

By Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

Pacific Coast Marine Windshields, Ltd. v. Malibu Boats, LLC (Fed. Cir. 2014)

Panel: Dyk (author), Chen, Mayer

In this case, the Federal Circuit determined—as a matter of first impression—that “the principles of prosecution history estoppel apply to design patents.” This case has a number of implications for design patent application strategy, including for applications filed under the Hague System.

Pacific Coast Marine Windshields Limited (“PCMW”) accused Malibu Boats (“Malibu”) of infringing U.S. Patent No. D555,070 (the “D’070 patent”). Here is a comparison of the patent drawings and the accused design, as shown in PCMW’s opening appellate brief:

As can be seen from this illustration, a major difference between these two designs is that the patented design features four circular vent holes while the accused design has three roughly rectangular-shaped holes.

The D’070 patent matured from a patent application filed (apparently pro se) by PCMW’s owner and CEO, Darren Bach. In the original design patent application, Bach claimed an “ornamental design of a marine windshield with a frame, a tapered corner post with vent holes and without said vent holes, and with a hatch and without said hatch, as shown and described.” The submitted figures included the following:

A design patent may contain only one claim. It is possible to claim multiple embodiments—but only if those embodiments involve the same inventive concept. The question of whether a claimed embodiment satisfies this standard is left largely to the examiner’s discretion.

In this case, the examiner decided that Bach’s application included five “patentably distinct groups of designs” and issued a restriction requirement. Bach did not challenge the restriction requirement. He elected to prosecute the design shown in Figure 1 above—i.e., the version with “four circular holes and a hatch.” He also amended the claim language, deleting the reference to any hole and hatch variations. So when the D’070 patent issued, it simply claimed “[t]he ornamental design for a marine windshield, as shown and described.” Bach later filed a divisional application for the no-holes-with-hatch variant, which matured into U.S. Pat. No. D569,782. But he did not pursue design patents for any of the other variations, including the two-hole variation shown above.

Malibu moved for partial summary judgment, arguing that PCMW’s infringement claim was barred by prosecution history estoppel. Malibu argued that PCMW surrendered the two-hole design during prosecution and that the accused three-hole design fell within the territory surrendered “between the original claim and the amended claim.” The district court agreed and entered judgment of noninfringement based on prosecution history estoppel.

On appeal, PCMW argued that the principles of prosecution history estoppel should not apply to design patents at all. It argued, among other things, that there was no good policy reason to extend the doctrine to design patents. The Federal Circuit did not agree, noting that “[t]he same principles of public notice that underlie prosecution history estoppel apply to design patents as well as utility patents.”

The Federal Circuit then considered whether prosecution history estoppel barred PCMW’s infringement claim. That issue “turn[ed] on the answers to three questions: (1) whether there was a surrender; (2) whether it was for reasons of patentability; and (3) whether the accused design is within the scope of the surrender.” The court concluded Bach did surrender the cancelled figures and that the surrender was done for reasons of patentability. In doing so, the Federal Circuit rejected PCMW’s argument that the restriction requirement was merely “administrative” or “procedural.” The court concluded “that, in the design patent context, the surrender resulting from a restriction requirement invokes prosecution history estoppel if the surrender was necessary . . . ‘to secure the patent.’”

However, the Federal Circuit decided that the accused design was not within the scope of the surrender. It rejected Malibu’s argument that “by abandoning a

design with two holes and obtaining patents on designs with four holes and no holes, the applicant abandoned the range between four and zero.” The court noted that “[c]laiming different designs does not necessarily suggest that the territory between those designs is also claimed.” Moreover, according to the Federal Circuit, neither party claimed that the three-hole design was a colorable imitation of the surrendered two-hole design. (The Federal Circuit expressly avoided answering “whether the scope of surrender is measured by the colorable imitation standard”—an interesting issue for another day.) Therefore, prosecution history estoppel did not bar PCMW’s claim.

On remand, it will be interesting to see how PCMW argues its infringement case. It seems difficult to argue that the accused three-rectangular-hole design is not a colorable imitation of the surrendered two-rectangular-hole design but that it is a colorable imitation of the claimed four-round-hole design.

This decision also has important implications for other cases. Design patent applicants often claim multiple embodiments. If the examiner approves those embodiments, the resulting patent will be (at least arguably) stronger and more flexible. Following Pacific Coast Marine, however, this is a riskier—or, at least, potentially more expensive—strategy. If an applicant claims multiple variations on a design and the examiner decides they are patentably distinct, the applicant must file divisional applications for the unelected variants to avoid prosecution history estoppel. And more applications means more fees.

This case also will be important when the United States becomes a party to the Hague System for the International Registration of Industrial Designs. The Hague System allows applicants to file up to 100 designs in a single registration, as long as the designs are all in the same Locarno class. But the PTO has indicated that it will apply its single-invention rule to any applications it receives via the Hague System. So applicants who include multiple designs in their Hague applications should expect restriction requirements, with all the attendant estoppel risks.