The US Patent Office has long favored a “compact prosecution” examination approach. With compact prosecution, once substantive examination begins, the Office focuses its attention on promptly conducting and concluding the examination. By reducing the duration of substantive prosecution, it is more likely that the case will be examined by an individual examiner and less likely that the examiner will have to re-learn the technology each go-round.

From the Patent Office perspective, the long backlog-queue does not hamper compact prosecution because substantive examination generally begins only once the patent application makes its way to the front of the backlog queue.

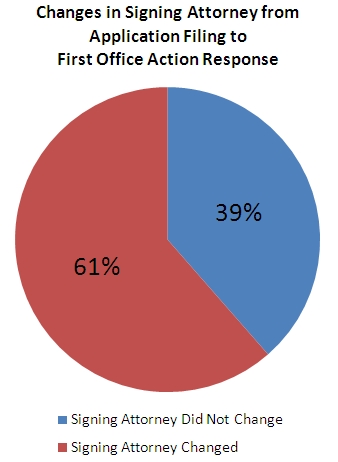

The applicant perspective is somewhat different. For applicants, substantive prosecution begins with preparing the patent application and eventually continues with office action responses and potential agreement on final claim language. I am beginning a project that looks at how the backlog impacts prosecution from the attorney side. As the first blunt analysis, I looked at the prosecution history files for 90 randomly selected recently issued patents and compared the practitioner signature of (1) the application as filed; (2) the first response to a non-final office action (if any); and (3) the issue fee transmittal.

Findings: The signing practitioner (attorney/agent) changed in 71% of the cases. Of the cases with response to a non-final office action rejection, the practitioner that signed the application was different from the practitioner that signed the initial response 61% of the time. (+/– 11% at 95% CI).

Great articles and it’s so helpful.

“Another thing it accomplishes is that it shows how good the data is.”

W

T

F

95% CI just means that the number next to it (the +/- 11%) corresponds to two standard deviations in the statistical distribution of his data points.

Nope. If you were to assume a normal distribution of data points around an average of 61, then the interval would be pretty close to 1.96*SD.

Can you assume that the data shows a normal distribution around an average in this case? You’d have to assume 50 for a yes/no question, which is how I calculated +/-31 for a set of 10.

I’m not even arguing about the mathematical calculation of CI95. I’m saying that there are times to use statistical tools, like CI95, and times not to use them. Your assumptions are massive in the case of such a small sample.

95% CI just isn’t meaningful

95% CI just means that the number next to it (the +/- 11%) corresponds to two standard deviations in the statistical distribution of his data points.

Every data set has a standard deviation, so every data set has a 95% CI which is just the standard deviation multiplied by two. What matters is how big that 95% CI is, not the fact that there is one.

I can pull up ten random patents and calculate a 95% CI of +/- 31 (i.e., a 62% range) for you, but what does that accomplish?

It would prove that any arbitrary set of data has a 95% CI, and therefore you shouldn’t be offended when someone else’s data has one. What you really mean to complain about is the 11%, not the 95%.

Another thing it accomplishes is that it shows how good the data is. 11% is a pretty big swing, but even skewing the pie chart by 11% still only brings it to 50-50, which still shows attorney changes in a significant proportion of applications. So yes, it’s very meaningful here.

IANAE, no one is questioning the existence of CI. You are the only one that even implied that. 95% CI just isn’t meaningful when a single new data point is going to move the raw number by well over 1% in one direction or the other. That was my point, which you either missed or ignored.

You’d be better off just coming out and saying “the sample set is too small to be statistically significant.”

If you’re going to report that you’re 95% sure that the % of cases with multiple practitioners signing is somewhere between 50 and 72%, then why bother? I can pull up ten random patents and calculate a 95% CI of +/- 31 (i.e., a 62% range) for you, but what does that accomplish? Would that lend credence to my data, or to the conclusions about 100,000+ issued patents that I drew from that set of ten patents?

Chris — I wanted to include the CI precisely because the sample size was so small that I didn’t feel that simply reporting the average would be responsible.

95% CI?

Every data set has a 95% confidence level, no matter how small. It’s simply two standard deviations, however wide or narrow that turns out to be. It’s the same “19 times out of 20” you see in all those polls.

You can question the usefulness of a percentage that is +/- 11%, but questioning the existence of a confidence level makes you sound like a Federal Circuit judge. In a bad way.

LOL. 90 patents? 95% CI?

Why even bother with CI when your sample size is less than one hundredth of a percent of the patents issued in a year?

It would be interesting to see more data, though. Specifically, how the number of attorneys signing responses per application has changed along with pendency over time, and # of attorneys vs. pendency of issued cases in a given month or year.

We shall defend ourselves to the last breath of man and beast. (William II, King of England)

I DO like continuation applications, and use them a lot. It’s simply that, being a smallish research company, we are generally fairly ahead or far enough away from our competitors that our specs don’t cover what they do. When filed. But as an app “ages” in the PTO, it’s more likely that the market will push the various possible embodiments in a field into just a few commercially advantageous ones. This increases the likelihood that two companies’ work will converge. If patents issued quickly, inventions would be more likely to be “frozen” in an earlier stage. The PTO’s backlog is both irritating (because we’d like patents faster) and advantageous (because we can amend toward convergence if it suits us).

And no, there’s nothing wrong with amending claims toward convergence with a competitor, it’s just that the public (and the PTO) whine about it like we’re “trolls” or something. The PTO should stop its whining, and recognize that it’s part of the problem.

Do you really think the CRXP you are telling me after I have been Jailed for 15 years, and forced into Bankruptcy while they stole my Claims has anything to do with what you are telling me?

I have the proof that this was a set up. A Lawyer has a duty to his client. and itis not to continue the Fraud.

sarah: I was shut down AS USUAL because of the truth factor.

Multiplying by zero will do that. Have you tried with a different truth value?

Patent_Medicine: it explains why applicants are able to draft claims to cover competitors’ products,

What is wrong with drafting claims to cover a competitor’s product, if that product is fairly within the invention you originally disclosed?

I can understand if people object that the claim has impermissible new matter or lacks written description support, but otherwise the patentee is surely entitled to claim any subset of the scope of his invention that is not invalidated by the prior art. After all, the original claims might have been drafted based on what aspects of the invention one’s competitors were likely to use, and there’s nothing wrong with refining that prediction as time goes by.

“it shows that a large part of the problem won’t change until the PTO changes.”

Here’s a hint: the PTO is the problem.

As far as submarines – they be sunk a while ago. drafting claims to cover competitor’s prodcuts is perfectly legit – O’ course, those claims gotta be supported by the app as filed. We do have somethin called the No New Matter law.

Ya don’t like continuations? Well perhaps that strategy don’t fit your clients’ products and bizness, but don’t rule them out on prinicple – ya be missin an opportunity to fully serve your clients if ya be doin that.

“From the Patent Office perspective, the long backlog-queue does not hamper compact prosecution because ….”

Dear Dennis:

I find this interesting, and disturbing.

Interesting, because it explains why applicants are able to draft claims to cover competitors’ products, and disturbing because it shows that a large part of the problem won’t change until the PTO changes.

“Submarine applications” and drafting claims to cover competitor’s products have been around a long time, but I had always thought of it as a few bad actors. It requires some effort (and lots of cash) on the applicants’ part to keep long chains of apps going. This is expensive, especially given that there’s no guarantee that a competitor will bring their product around to come under your specification. Publication of apps also makes this less likely.

I have always been a fan of speedy prosecution, and achieving closure on an invention family. But now I find myself in a position of having originally-files applications (not continuing apps) taking so long to be examined that, yes, I see competitors moving their R&D into space that is easily covered by amendments to existing claims.

The USPTO absolutely needs to view “backlog” as running from time of filing to time of final resolution of the application.

I tried to tell you what is really going on, but I was shut down AS USUAL because of the truth factor. But this is just a blog that culls anything that “IT” sees as negative to it’s cause. This blog is only here to spread one sided views, or to confuse little Robots.

I’m not surprised by the results given the time delay between filing and examination. Perhaps I am missing the point of the post. I believe a more meaningful evaluation would be to determine whether preferential treatment is afforded to large firms versus sole practitioners.

Speaking about Michael R. Thomas,

6, your IDS jaunts are slightly below the typical MRT ramble on the “who cares” scale.

Case 5 (IDS 6&7)

These two IDS’s had 6 references each. All references were reasonably pertinent to the claims, some very pertinent. Probably some of the best prior art I found. Had I have noticed the IDS at the beginning of the search I may well have been able to make a rejection, although that is unlikely. As is, the case is allowed and the IDS’s got looked at last due to my overlooking them until now.

If it is a foreign origin application, often the originating partner signs the application papers. But then when the tough work comes to respond to an OA, the (more junior) practitioner who did the work often signs the response papers.

No wonder the gods ate their young.

The idea is to have self reliant associates who can be handed a disclosure and run with it through issue.

Assuming you trust your associates. Or want them to be fully competent and self-reliant so they could take your training and score a higher-paying job at a competing firm if for whatever reason you make their professional lives unbearable.

The problem with being at the top is that it’s really scary to look down.

“In some IP assembly line firms, associates are dedicated to prosecution or patent drafting early in their careers. In my first IP firm, even though I had my PTO license, I spent the first 1 1/2 years only doing prosecution work while other associates were being trained to only draft patent applications. Needless to say this silo model leaves something to be desired from a professional accomplishment and growth perspective, and is the primary reason I left after only 2 years.”

What kind of weird training is that? I was trained to do everything, right from the start. The idea is to have self reliant associates who can be handed a disclosure and run with it through issue.

Mr. Boundy, yes, please do gather up the materials at hand and post them somewhere for the rest of us to see. As for Mr. Bahr, I understand him to be purely the product of the PTO, in that he has never worked for any other employer (or been self-employed) since college. A bit more churning in the top ranks of the PTO might do everyone a world of good.

Altoid Both for our cases and for other cases we are monitoring, there appear to be wide disparities between examiners particularly in the way written description is being applied and also we are aware of 102 art that has not been cited (not our cases, of course).

I think it’s Rule 99 that allows you to submit art to be considered in third party cases. Alternatively, you can wait until after the third party has received the Notice of Allowance and shortly before issuance to dump the 102 art directly in the third party’s lap via Fed Ex, reminding them of their duty of candor with the USPTO. Usually this is done using an intermediary that has no public association with the client who has an interest in the third party’s case. MOO HOO HOO HAW HAW HAW!!!!!!!!!!

Even though I’m in a small firm, our partners usually sign the new apps if they are foreign origin, which they nearly all are. Given that clients often send the papers the day before the bar date, I wouldn’t even want to handle this aspect. I have enough deadlines as it is.

Is compact prosecution always such a great idea? In complicated cases, it may take a while for the patentability of things to sink in, and with many complex ideas it is best to study, little by little, to get the whole picture.

As for different signatories, that is a bad thing if it reflects that applications and clients are being passed around depending on who is available or who needs billable hours. We have had some clients object on that basis (actually, on the more personal basis that they like to know and talk to the guys in charge of their patents). I here a lot of grumbling from clients about other firms that pass them around like a hot potato, even though they pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for patent work.

It can be a good thing if it reflects a second look. Some applications are so complicated, or the claims-to-prior-art interface so tricky, that a second opinion (other than the examiner) is a good idea. Also, if a client has many applications going, cross-training is a good idea to make sure the entire prosecution team is familiar with all the applications and all the prior art and all the arguments for patentability.

Now we have a rule here that no more than two attorneys may work on any single case, and that those two attorneys be consistent through a client’s portfolio.

For foreign drafted applications, these should be carefully reviewed by a patent attorney prior to national stage, to make sure the spec and claims are suitable, and also to make sure the translation is sensible (this can kill an application). After that, it is most efficient for the same patent attorney to handle office action responses, which includes incorporating instructions from the originating foreign firm. I think this should not be passed around the firm.

David Boundy, I am with you on expecting Examiners to actually examine every limitation of the claims. Some other posters have mentioned that the appropriate response to a final rejection that ignores claim limitations is to appeal. I tend to agree. Nine times out of ten, the Examiner will reopen with a non-final rejection. If the case does go to the board, then it will be an easy reversal of the rejection.

David Boundy, I am with you on expecting Examiners to actually examine every limitation of the claims. Some other posters have mentioned that the appropriate response to a final rejection that ignores claim limitations is to appeal. I tend to agree. Nine times out of ten, the Examiner will reopen with a non-final rejection. If the case does go to the board, then it will be an easy reversal of the rejection.

Speaking of compact prosecution, I really wish there was some way to bring uneven examination to the attention of the examiners and/or supervisors. Both for our cases and for other cases we are monitoring, there appear to be wide disparities between examiners particularly in the way written description is being applied and also we are aware of 102 art that has not been cited (not our cases, of course). There really ought to be a way to raise such things during examination with the Examiner; it would be much more efficient (than post-issue litigation or re-exam) and also make the PTO look better because the patents issued would be stronger (i.e., “better”).

In some IP assembly line firms, associates are dedicated to prosecution or patent drafting early in their careers. In my first IP firm, even though I had my PTO license, I spent the first 1 1/2 years only doing prosecution work while other associates were being trained to only draft patent applications. Needless to say this silo model leaves something to be desired from a professional accomplishment and growth perspective, and is the primary reason I left after only 2 years.

You want to know who wrote the first deep blue Application… THAT”S EASY. I even spent an hour on the phone with him. He will be very easy to find.

They often get their hours by filing the applications, paying the issue fees, sending form letters, etc.

Where do they find the clients who believe those menial tasks require the undivided attention of the very highest hourly rate in the firm?

If I were buying an hour of a partner’s time, I’d much rather get it in the form of complex advice or reviewing a junior’s claims than pushing paper around.

In my experience, patent agents draft a lot of patents. Patent agents move around quite a bit. With a three year wait for the first office action, it’s quite often the case that the drafter is long gone.

Dennis – I think you would be better served by comparing customer numbers. If you see that the customer number changed, than the law firm probably changed and there really has been some disruption in the continuity of care of the patent application.

Dennis: I think a way to address the issue of different attorneys signing would be to check to see whether the signing attorney is still with the firm. If so, then it would be reasonable to argue that prosecution wasn’t impacted (much) by delay … although, speaking for myself, I found that I often had to re-familiarize myself with the case when the office action finally came in. I also agree that many non-domestic applications are not (much) impacted by change of domestic counsel. Finally, I believe signature on the issue fee transmittal would be much less relevant in a firm of almost any size than the signature on the application and first office action, but I don’t have a good substitute for that.

With roughly half of all U.S. applications being of foriegn origin (based on an already prepared and filed foreign application), who signs the U.S. equivalent application versus who signes the first amendment would seem to be much less of an efficiency issue for all of those applications?

As others have pointed out, juniors, even with reg numbers, may not necessarily sign papers. I didn’t sign things for the first 6-8 months of my employment, even though I had my reg number before I was hired.

That said, I’ve been here two years and have not yet prosecuted an application that I drafted, so the point about the backlog is an important one… Although I’ve not changed firms, I have several fellow patent agents that have, within that period of time, and so will probably not prosecute anything they’ve drafted.

In my firm, partners generally sign new applications, while the “working attorney” (often an associate or patent agent) may sign the responses. Associates and agents generally work under the partner’s supervision. So, the name change you focused on may not reflect a real change in responsibility/oversight or discontinuity.

Quoting Mr. Bahr, Mr. Boundy wrote, “there is no obligation for an examiner to consider claim language element-by-element”

I bet they call this the “Broadest Reasonable Omission”

In my personal experience, the attorney who signs the patent application for filing purposes is often not the attorney who prepared the application. In many instances, the signing attorney is in-house counsel, the reviewing partner for the project, or the responsible partner for that client. I have personally drafted nearly 100 patent applications and am not listed as the signing attorney on any of them.

Mr. Moose wrote: In my experience in a leveraged firm, the attorney whose name appears on the filing will likely have had little to no correslation with who actually did the work.

I agree. The senior attorneys need to be able to bill for something and their billing rates are typically too high to draft or prosecute applications in any significant volume. They often get their hours by filing the applications, paying the issue fees, sending form letters, etc. You can’t infer anything from who signed what.

I’ve met Mr. Bahr and I must say, Iza surprised at these positions being taken – they clearly be incorrect and an abdication of responsibility – that just don’t sound like Bahr (not to say that aint be happenin).

I gotta wonder – is someone pulling the Bahr-man’s strings? Be he dancin the internal politic?

The US Patent Office has long favored a “compact prosecution” examination approach. With compact prosecution, once substantive examination begins, the Office focuses its attention on promptly conducting and concluding the examination.

This is only half accurate, the PTO has a double standard. Yes, the PTO favors “promptly concluding” examination — two Actions. But “promptly conducting?” NO. I recently was asked to consult on a decision on petition signed personally by Acting Assistant Commissioner for Examinaitno Policy Robert Bahr — THE PERSON responsible for setting “compact prosectuion” policy. AACEP Bahr adamantly insists on three remarkable propositions:

(a) jurisdictionally, he (and his petitions-deciding machinery) have no responsibility for enforcing any rule relaing t ocompletene or c\”compact prosectuion” of Actions. AACEP jurisdictionally states that examienrs can turn out two Actions, no matter how thin, and walk home with their counts, with no supervisory oversight.

(b) Mr Bahr states that [I don’t have the paper in fron of me, I’m working from memory] “there is no obligation for an examiner to consider claim language element-by-element” and an action that totally ignores claim language, or that adds a “new ground of rejection” by considering long-pending claim language for the first time, may nonetheless be made final.

(c) Supreme Court, Federal Circuit, Board and Directors’ precedential decisions on defintions of legal terms such as the defintion of “new ground,” appealable subject matter, “agency action,” etc. can be ignored. Mr Bahr knows better than any of those dopes that have all the Presidential appointment and Senate confirmation baggage. Mr Bahr believes hehas the personal authority to make up his own defintions of these terms, he doesn’t need to distinguish precendent, and he doesn’t have to cite precedent to support his views. His own personal opinion trumps them all.

Mr Kappos, Mr. Stoll, Ms. Barner – you want to know where your RCE and Appeal problems come from? I’ll show you the papers. Give me a couple weeks to put together a presentation. You know where to find me.

“In general, I would estimate that attorneys can practice 7-10 years before they see a case where they drafted, prosecuted, and had that same application issue”

It only took about 3 for me to start having those come in.

“Don’t these two sentences absolutely contradict one another? Either you sign your own work or you don’t.”

I do, unless I’m not there to sign it, which is a rare occasion. Perhaps twice a year. What I was getting at is that nobody “ghost writes” at my firm.

Some practitioners “ghost write” patent applications that end up being signed by a lawyer supervising the ghost writer or even an in-house counsel that may have had little direct interaction with the contents of a patent application or an office action response.

I think that any analysis of who is signing patent office transmittals would be limited somewhat by the above considerations, along with law firm mergers, attorney employment changes, death, retirement, law firm name changes, and yes, even practitioner name changes.

From an in-house prospective, there are a number of reasons as well as to why the signature may be different: 1) the attorney handling the case no longer works at that company; 2) there was a department/docket re-organization and the attorney no longer handles this subject matter; 3) the attorney was not in the office the day this paper was filed, so a colleague signed; 4) the subject matter was licensed out/assigned and the other party or outside counsel now handles; or 5) outside counsel now is handling. There are probably a lot more.

In general, I would estimate that attorneys can practice 7-10 years before they see a case where they drafted, prosecuted, and had that same application issue.

There are many reasons the private practitioner world is not analogous to the PTO’s side. At my previous previous firm, a really big firm, the partner’s signature was usually on the gravy work, and the associate’s signature was usually on the labor-intensive work.

Speaking from a “foreign” perspective (Australia), I would caution against making any assumptions about the significance of the signing US attorney for overseas-originating cases.

I have been in the profession long enough now that I have clients for whom I have drafted the original priority application, and seen the case through to grant in a number of countries, including the US.

While we value the expertise and input of all of our overseas associates, in relation to local law and practice, the substantive matters of understanding the applicant’s objectives and interest, and providing advice in relation to rejections and potential amendments and replies, lies primarily with those of us who deal directly with the end client.

We are familiar not only with the US prosecution history, but also with changes in the applicant’s business strategies and interests, and with events that may occur in the prosecution of other corresponding national applications.

While there is certainly benefit in working with a single attorney throughout examination, this need not be (and quite commonly is not) the same attorney who signed the filing documents. And in the interests of providing our clients with an overall cost-effective service, we endeavour to minimise duplication of work by providing clear instructions to the foreign prosecuting attorney in which there is clear delineation between our input and the areas in which their local expertise is essential and/or most valuable.

I would generally hope that any attorney could comprehend and act on instructions that I have prepared, even if they have not been previously involved, without it having a significant impact on the efficiency of prosecution.

“Since I’m not in the office, I can’t sign it, so my assistant will replace my name with a colleague’s name and have him sign. Since we’re all in the same firm, it doesn’t matter.

Anon E Mouse, that’s interesting. At my firm, we all sign our own work. ”

Don’t these two sentences absolutely contradict one another? Either you sign your own work or you don’t.

Dear PTO – in my lifetime, please. Nearly one-third of US sole patent practitioners are 60 or older (ref: AIPLA). A sole practitioner drafts utility applications with a 17% chance that a sixty-year-old solo US business owner dies within five years (ref: VSA, LP). So, perhaps about 5% (or more) of Professor Crouch’s red pie wedge is where the case pendency to first action easily outlives the practitioner. Oh well, back to sowing and reaping. (Ecclesiastes 11:4).

Quick IDS project update. Case 5.

3 references, all half pertinent to the claims. Only one is anticipatory for one claim, and only because the attorney accidentally drafted his claim in terms that read all over what he knows to be prior art.

FYI, every claim in the case is getting a blatant 102e save 2 which are ez 103’s. Yes it took awhile to find the 102e primary.

“For the most part, the applicant has not changed firms”

Perhaps not, but it might make an interesting comparison.

I’ve personally done a lot of work that is filed without my signature. Some of it has to down with the partner/client issue. Other times, it has to do with multiple owners where the signing atty. may represent all owners.

Is another possibility that the PTO backlog is now so extensive that the original attorney or agent died of old age waiting for the first office action came in?

[That was only a partial joke, but additional reasons are patent-work-outsourcing, mergers, acquisitions, and bankrupcies (with consequent attorney changes) in that now-multi-year intervening time period, plus a lot of law firm and company employee turnover.]

I would be more interested in how many continuations and CIP’s [not RCE’s] end up assigned to a new examiner, since that is real inefficiency.

Ditto Anon’s point. There are many reasons not to draw any conclusions based on signatures.

“You suggest that “some other agent may have signed the response because he was available that day, and nobody cared because the entire firm was of record.” Could you explain further? Is that something that happens often?”

I wouldn’t say often, but it absolutely happens. The situation is usually this: I get an office action, draft a response, forward the draft response to a client, and the client then responds on some day I’m not in the office asking me to file the response that day (I deal with some pretty demanding in-house attorneys). Since I’m not in the office, I can’t sign it, so my assistant will replace my name with a colleague’s name and have him sign. Since we’re all in the same firm, it doesn’t matter.

Anon E Mouse, that’s interesting. At my firm, we all sign our own work.

In my experience in a leveraged firm, the attorney whose name appears on the filing will likely have had little to no correslation with who actually did the work. I’ve worked where the most senior partner always filed all new applications; alternately the partner whose client was filing the appl signed on inital filing. The attorney filing the amendment may or may not have prepared it himself, or given any significant review to the amendment before filing, or given any consideration to portfolio-wide prosecution strategy WRT other patents of the applicant or those of their competitors. The attorney filing a foreign-origination app is almost irrrelevant, particularly WRT the attorney who performs later prosecution (not to be confused with the attorney who signs those amendments).

This is to say nothing of the cases already mentioned where one parter signs for another due to simple availability on the day of filing.

I don’t think I can go along with your premise that continuity in name on the papers has any impact, DC.

You suggest that “some other agent may have signed the response because he was available that day, and nobody cared because the entire firm was of record.” Could you explain further? Is that something that happens often?

I don’t know how often it happens, but I could imagine it happening if the senior agent who usually signs has reviewed a first draft, but is out of the office when the final draft is ready and due. The review process at that point might be clerical or not required at all, but you’d still need someone else with an agent number to sign. It just occurred to me as a possible explanation why one might see different signatures within the same firm.

IANAE — For the most part, the applicant has not changed firms. Rather, as you suggest, it appears that the prosecution is being delegated to a junior agent.

You suggest that “some other agent may have signed the response because he was available that day, and nobody cared because the entire firm was of record.” Could you explain further? Is that something that happens often?

Dennis,

Have you accounted for whether the two signing practitioners are in the same firm? It’s possible that the agent who knew the technology well enough to draft the application is still available to be consulted on technical matters, but the prosecution was delgated to a junior agent for training purposes or because he just got his agent number or some other reason. Or for all we know, some other agent may have signed the response because he was available that day, and nobody cared because the entire firm was of record.