They’re Alive: Federal Reserve Banks are “Persons” under the AIA

by Dennis Crouch

Over the past couple of decades, some banks have been making efforts to appear more personal & humane. All that has come to fruition with the Federal Circuit's decision in Bozeman Financial LLC v. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, et al. In its opinion the court explained that yes, the Federal Reserve is a person too -- at least with regards to the right to file an inter partes review (IPR) or post grant review (PGR) petition.

The AIA permits "a person who is not the owner of a patent" to petition for IPR/PGR requesting cancellation of a patent. In 2019, the Supreme Court took-up a case where the US Postal Service (USPS) had filed for review of a patent owned by Return Mail, Inc. Return Mail, Inc. v. U.S. Postal Serv., 139 S. Ct. 1853 (2018). In its decision, the Supreme Court held that the USPS is not a person under the statute. The court stuck to its "longstanding interpretive presumption" that Congress's use of the term "person" does not "include the sovereign."

In the present case, the twelve Federal Reserve Banks jointly petitioned the USPTO to challenge Bozeman's U.S. Patent Nos. 6,754,640 and 8,768,840. The PTAB complied and cancelled all of the claims -- finding them ineligible under Section 101.

On appeal, the patentee asked that the entire case be thrown-out under Return Mail. However, the Federal Circuit refused -- finding that the Federal Reserve Banks are sufficiently separate and distinct from the United States Gov't.

The Federal Reserve Banks were established as chartered corporate instrumentalities of the United States under the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. Unlike the Postal Service, which was at issue in Return Mail, the Banks’s enabling statute does not establish them as part of an executive agency, but rather each bank is a “body corporate.” Like any other private corporation, the Banks each have a board of directors to enact bylaws and to govern the business of banking. Moreover, the Banks may sue or be sued in “any court of law or equity.” . . .

The Banks are not structured as government agencies. The Banks do not receive congressionally appropriated funds. 12 U.S.C. § 244. No Bank official is appointed by the President or any other Government official. 12 U.S.C. § 341. Moreover, the government exercises limited control over the operation of the Banks. Instead, the “direct supervision and control of each Bank is exercised by its board of directors.” 12 U.S.C. § 301. And the Banks cannot promulgate regulations with the force of law. Scott v. Fed. Reserve Bank, 406 F.3d 532, 535 (8th Cir. 2005). For these reasons, we conclude that the Banks are distinct from the government for purposes of the AIA. We recognize that there may be circumstances where the structure of the Banks does not render them distinct from the government for purposes of statutes other than the AIA. For purposes of the AIA, however, we conclude the Banks are “persons” capable of petitioning for post-issuance review under the AIA. The Board therefore had authority to decide the CBM petitions at issue here.

Note here that the court did not mention the Fed Reserve Board of Governors - whose members are appointed by the president - or the fact that the Board of Governors appoint a substantial portion of the directors of each bank. The outcome here is also interesting to consider with respect to the corporate structure of various public universities around the country.

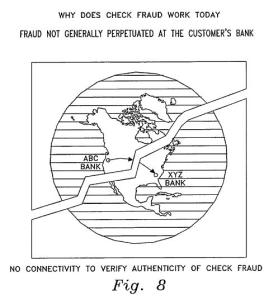

Moving on to the merits, of the eligibility decision, the Federal Circuit affirmed that the claims were directed to the abstract ideas of "collecting and analyzing information for financial transaction fraud or error detection" ('840 patent).

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.