Guest Post by Michael Williams. Williams is a UK and European Patent Attorney and Partner at the London based Cleveland-IP firm.

In the book “Through t he Looking-Glass”, Alice compares her drawing room to the one reflected in the mirror. She notes that everything is the same “only the things go the other way”.

he Looking-Glass”, Alice compares her drawing room to the one reflected in the mirror. She notes that everything is the same “only the things go the other way”.

In the recent Alice Corp[1] decision, the US Supreme Court set out a framework for assessing whether claims are patent eligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101. In this article I shall compare this framework with that used by the European Patent Office, and consider the similarities.

The US Alice Approach

In a memorandum dated June 24, 2014, the USTPO has set out its Preliminary Examination Instructions to the Patent Examining Corps in view of the Alice Corp decision[2]. In the Instructions, a three stage framework is set out which is summarized below:

- Determine whether the claim is directed to one of the four statutory categories of invention, i.e., process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter. If the claim does not fall within one of the categories, reject the claim as being directed to non-statutory subject matter (§ 101).

- If the claim does fall within a statutory category, determine whether the claim is directed to an abstract idea. If not, proceed with examination of the claim for compliance with other statutory requirements.

- If an abstract idea is present in the claims, determine whether any element, or combination of elements, in the claim is sufficient to ensure that the claim amounts to significantly more than the abstract idea itself. If there are no meaningful limitations in the claim, reject the claim as being directed to non-statutory subject matter.

The Examiner should then proceed to examine the claim for other patentability requirements, whether or not a rejection under § 101 has been raised.

I have illustrated the three-stage “Alice” approach in Figure 1.

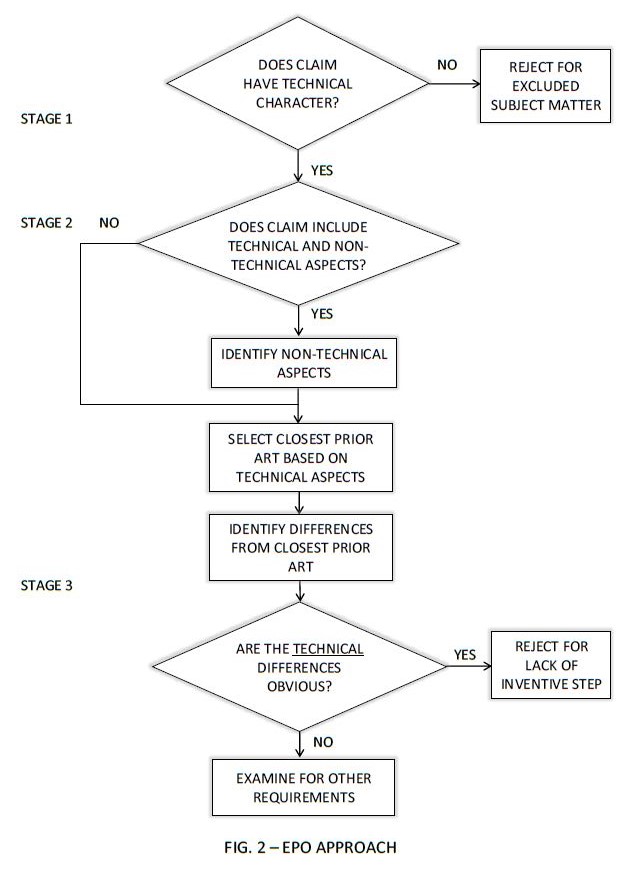

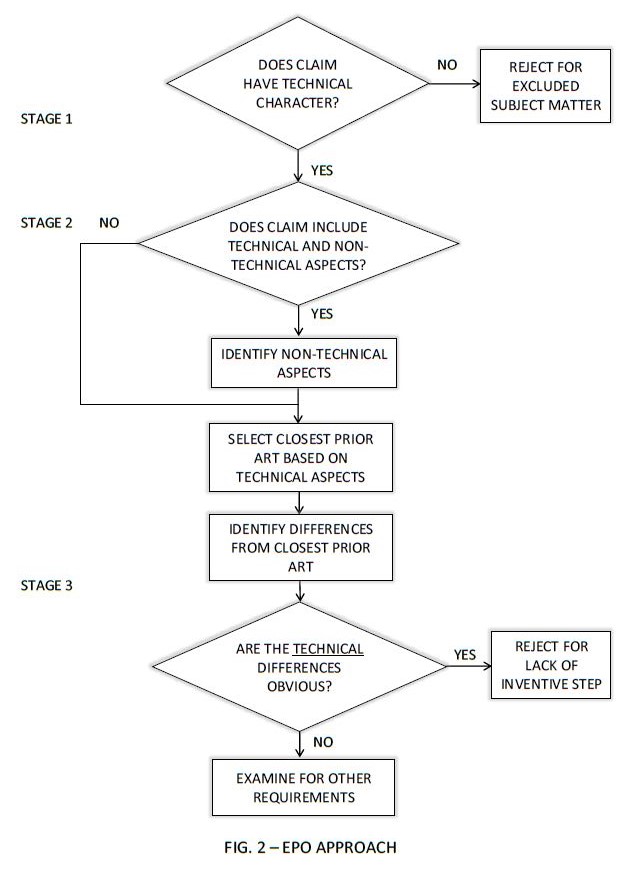

The EPO approach

The approach of the EPO to claims with potentially excluded subject matter is summarised below.

- Examine the claim to establish whether it relates to excluded subject matter as such. This is done by assessing whether the claim has a technical character. If there is no technical character at all, the claim is rejected under Article 52 EPC for relating to excluded subject matter as such[3] .

- If the claim has technical character, it is examined for novelty and inventive step. In the case of inventive step, it is determined whether the invention involves an inventive step in a technical field. If the claim lacks an inventive step in a technical field it is rejected under Article 56 EPC.

In the case of a claim with a mix of technical and non-technical features, the following steps are followed when assessing inventive step[4]:

- Identify the non-technical aspects of the claim,

- Select the closest prior art on the basis of the technical aspects,

- Identify the technical differences from the closest prior art,

- Determine whether or not the technical differences are obvious.

If there are no technical differences, or if the technical differences are obvious, the claim is rejected for lack of inventive step.

I have illustrated the overall approach in Figure 2. In order to facilitate comparison, I have separated the approach into stages which correspond roughly with those of the USPTO approach. I have also assumed that there are differences between the claimed invention and the prior art (otherwise there would be lack of novelty).

Comparison of the two approaches

A comparison of the flow charts in Figures 1 and 2 shows a striking similarity between the first stages of each approach. In each case, it is in effect determined whether the claim relates to no more than excluded, or ineligible, subject matter. In both cases this acts as a filter to weed out claims which do not have any technical subject matter.

The second stages of each approach also bear comparison. In the case of the EPO, it is determined whether or not the claim includes both technical and non-technical features. In the case of the USPTO it is determined whether the claim is directed to a (non-technical) abstract idea. However, since the claim must contain some technical subject matter (or it would have been weeded out at stage one), this is akin to determining whether there is a mix of technical and non-technical features. In both cases, the second stage flags up cases where there might still be a problem with excluded subject matter.

In the third stage of each approach we come to the nub of the matter. It is here that borderline cases will stand or fall. It is therefore worthwhile analysing this stage of each approach.

In the case of the EPO approach, the technical and non-technical features of the claim are first separated out. The technical features which are not present in the prior art are then identified. It is then determined whether or not those technical features are non-obvious. In doing so, it is assumed that the non-technical features are already present in the prior art. If the technical features which are not present in the prior art are obvious, the claim is rejected for lack of inventive step.

In the case of the USPTO approach, stage three involves determining whether there are any elements in the claim which amount to significantly more than the abstract idea itself. This in effect requires two steps, as follows:

- Identify the elements which are not an abstract idea, and

- Determine whether those elements amount to significantly more than the abstract idea itself.

It is notable that step a is similar to the EPO approach of identifying the non-technical aspects of the claim.

With regard to step b, this begs the question: how much more is “significantly more”? According to the Instructions there must be “meaningful limitations” in the claim, but how meaningful do they have to be?

We can assume that the elements which must be “significantly more” than the abstract idea are technical (since otherwise the claim would have been weeded out at stage one). It is also the case that, in order to be “significantly more”, those technical elements must be meaningful. If they must be meaningful, does this mean they must contain the inventive concept?

My guess is that, in practice, persuading the USPTO to allow claims of this type is probably going to involve arguing that the elements which are significantly more than the abstract idea are somehow tied in with the inventive concept. Otherwise they would not be “meaningful”. This then starts looking very much like arguing for non-obvious technical subject matter; in other words, an inventive step in a technical field.

There will of course be differences between the two approaches, not least due an imprecise alignment of the concepts of “abstract” and “non-technical”. However it seems to me that both approaches are seeking to achieve something similar, namely, an assessment of whether the innovation itself lies in a non-excluded field.

Thus, to my mind, we are now in a situation where, in practice, the two approaches are considerably aligned, albeit “the other way round”.

Conclusion

Conclusion

As readers of the book will recall, when Alice actually goes through the looking glass, she finds it to be completely different from what she first saw. I suspect that, as case law and practice develop, we will find that USPTO and EPO practice will differ. However it is notable that, at least on the face of it, there are now considerable similarities.

= = = = =

[1] Alice Corporation Pty. Ltd. V CLS Bank International, et al

[2] http://www.uspto.gov/patents/announce/alice_pec_25jun2014.pdf

[3] Guidelines for Examination in the European Patent Office G-II, 2.

[4] Guidelines G-VII, 5.4

he Looking-Glass”, Alice compares her drawing room to the one reflected in the mirror. She notes that everything is the same “only the things go the other way”.

he Looking-Glass”, Alice compares her drawing room to the one reflected in the mirror. She notes that everything is the same “only the things go the other way”.

Software company FireStar has filed suit against open source seller Red Hat, alleging patent infringement. The suit, filed in the Eastern District of Texas, asserts infringement of U.S. Patent No. 6,101,502 that is directed to a method of interfacing an object oriented software application with a relational database. Red Hat recently purched JBoss maker of the specific accused product

Software company FireStar has filed suit against open source seller Red Hat, alleging patent infringement. The suit, filed in the Eastern District of Texas, asserts infringement of U.S. Patent No. 6,101,502 that is directed to a method of interfacing an object oriented software application with a relational database. Red Hat recently purched JBoss maker of the specific accused product

![Apple-logo[1]](https://patentlyo.com/media/2015/02/Apple-logo1-256x300.jpg)