In this post, Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law, examines the design patent components of the Federal Circuit’s recent Ethicon decision. Dennis’s discussion of the utility patent’s indefiniteness issue is here.

Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. v. Covidien, Inc. (Fed. Cir. Aug. 7, 2015) Download opinion

Panel: Chen (author), Lourie, Bryson

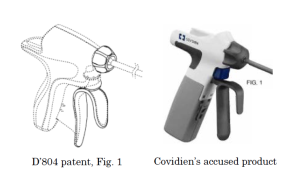

Ethicon alleged that Covidien’s Sonicision cordless ultrasonic dissection device infringed various utility and design patents. Each of the asserted design patents claimed a portion (or portions) of a design for a surgical device. A representative image from each patent is shown below:

All of the asserted design patents claimed at least some portion of the design of the u-shaped trigger. Three of them also claimed the design of the torque knob and/or activation button.

The district court granted summary judgment that the design patents were invalid for lack of ornamentality and not infringed. Ethicon appealed.

Validity

The Federal Circuit reversed the grant of summary judgment of invalidity. A patentable design must be, among other things, “ornamental.” The Federal Circuit has interpreted this as, essentially, a type of non-functionality requirement.

In deciding that the designs were invalid as functional, the district court relied on a number of factors from Berry Sterling Corp. v. Pescor Plastics, Inc. In Berry Sterling, the Federal Circuit stated that, in addition to the existence of alternative designs:

Other appropriate considerations might include: whether the protected design represents the best design; whether alternative designs would adversely affect the utility of the specified article; whether there are any concomitant utility patents; whether the advertising touts particular features of the design as having specific utility; and whether there are any elements in the design or an overall appearance clearly not dictated by function.

In their appellate briefs, the parties disputed the relevance and relative weight of these factors. Ethicon noted the significant tension between Berry Sterling and other controlling precedents, arguing that “[b]efore and after Berry Sterling, this Court has treated the presence or absence of alternative designs that work as well as the claimed design as a dispositive factor in analyzing functionality.” Covidien, on the other hand, argued that the availability of alternative designs was not a dispositive factor.

In its decision, the panel attempted to harmonize the conflicting precedents by stating that the Federal Circuit had not, in fact, previously “mandated applying any particular test for determining whether a claimed design is dictated by its function and therefore impermissibly functional.”

The panel noted, however, that the Federal Circuit had “often focused . . . on the availability of alternative designs as an important—if not dispositive—factor in evaluating the legal functionality of a claimed design.” The panel then recast the Berry Sterling factors as only being applicable “where the existence of alternative designs is not dispositive of the invalidity inquiry.” The panel did not explain how or when the existence of alternatives would—or would not be—dispositive as to validity. However, it did make it clear that “an inquiry into whether a claimed design is primarily functional should begin with an inquiry into the existence of alternative designs.”

Although Ethicon had submitted evidence of alternative designs, Covidien argued they were not “true alternatives because, as the district court found, they did not work ‘equally well’ as the claimed designs.” The Federal Circuit disagreed with Covidien for two main reasons:

First, the district court’s determination that the designs did not work “equally well” apparently describes the preferences of surgeons for certain basic design concepts, not differences in functionality of the differently designed ultrasonic shears. . . . Second, to be considered an alternative, the alternative design must simply provide “the same or similar functional capabilities.”

The Federal Circuit also decided that, in finding the claimed designs to be functional, the district court “used too high a level of abstraction,” focusing on general design concepts—for example, on the concept of an open trigger—instead of “the particular appearance and shape” of the claimed design elements. The Federal Circuit therefore reversed the district court’s summary judgment of invalidity.

Infringement

This decision also provided some useful clarification about how to apply the design patent infringement test, as formulated by the en banc Federal Circuit in Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc. In the wake of Egyptian Goddess, some lawyers have argued that: (1) a court must (almost) always consider the prior art when analyzing design patent infringement; and (2) in certain circumstances, the prior art can be used to broaden the scope of a patented design.

In Ethicon, the panel helpfully—and accurately—clarifies the rule of Egyptian Goddess, noting that:

Where the claimed and accused designs are “sufficiently distinct” and “plainly dissimilar,” the patentee fails to meet its burden of proving infringement as a matter of law. If the claimed and accused designs are not plainly dissimilar, the inquiry may benefit from comparing the claimed and accused designs with prior art to identify differences that are not noticeable in the abstract but would be significant to the hypothetical ordinary observer familiar with the prior art. (Citations omitted.)

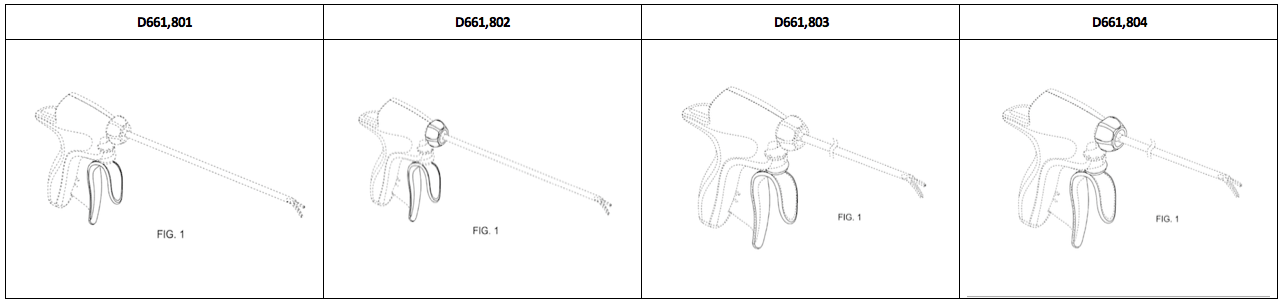

In this case, the district court engaged in a “side by side comparison between the claimed designs and the design of Covidien’s accused shears” and determined that they were plainly dissimilar and, therefore, the design patents were not infringed. The Federal Circuit provided these images as a representative example:

The Federal Circuit disagreed with Ethicon, finding no genuine dispute of fact on the issue of infringement. According to the court, the designs were only similar “[o]n a general conceptual level.” And because the designs were plainly dissimilar, the court “did not need to compare the claimed and accused designs with the prior art.” The court therefore affirmed the grant of summary judgment of non-infringement.

Wow! its amazing education blog. i love such a nice information. thanks for sharing with us.

Quality Writing Services

PS: courts loved the Federal Circuit’s pronouncement in Egyptian that abolished the necessity of a detailed verbalization of a claimed design during Markman claim construction. …. If they don’t have to do something, they won’t. And they don’t have to look at the prior art if they find the two designs “sufficiently distinct”.

Let’s set aside for the moment the issue of what exactly “detailed” is supposed to mean in the context of “detailed verbalization of claimed design.” I don’t think courts have an issue at all with the idea of providing some verbalization of their reasoning for finding non-infringement (if they do, that’s a much larger issue than the design patent issue).

The CAFC’s rule that rendered a “detailed verbalization” optional in certain circumstances makes perfect sense in terms of both fairness and judicial economy. For instance, why bother with a “detailed verbalization” of a complex patented design that is asserted against a far simpler design that no reasonably person could find infringing? Why is any more detailed analysis necessary beyond, say, “the patented design consists of five complex polygons and the defendant’s consists of one circle”? It doesn’t matter what the prior art is. There is no more analysis required. Requiring more consideration of additional “factors” in such circumstances just increases the cost to defendants. If courts want to create those kinds of “required” considerations than they better have lengthy briefing on the underlying rationales and policy issues going to into such considerations.

Otherwise we end up with pointless and harmful nonsense like considering whether the design was “licensed” when determining its obviousness under 103.

That’s some serious strawmanning there Malcolm.

When was the last time you saw a case go to court as easy and as requiring as little analysis as your knocked down example?

And you felt compelled to print this twice…?

That’s some serious strawmanning there Malcolm.

There’s no strawman. I’ve just explained why “detailed verbalization” is not necessary (or even advisable) in every design patent infringement case.

If it’s too difficult for you to follow, I can explain it again using smaller words for you.

…and I have pointed out that no one would use the argument so easily knocked down of your “example.”

Do you need me to list the definition of “strawman” and hold your hand as to why your “example” fits?

“anon” I have pointed out that no one would use the argument so easily knocked down of your “example.”

People assert design (and utility) patents all the time that are rightfully and properly tanked or found to be non-infringing on summary judgment with appropriate minimal analysis.

Welcome to planet earth.

Great.

Still does not address your rather obvious strawman.

see my post under 2.3.2.1

No less than 1300 pages of “consensus”.

I don’t know how one can determine infringement unless one knows what is new.

This “substantially distinct” rule of law, that can be made without reasoning, is cannot be a proper rule of law.

Ned, just to ask a philosophical question, why should any patent claim be a “nose of wax” that waxes and wains for infringement scope purposes depending on what prior art one defendant finds compared to what art another defendant finds? For utility patents, the Fed. Cir. has criticized the old doctrine of “reading claims narrowly to save them from prior art”, and IPRs certainly do not either. Nor have we seen any mention in years of ignoring claim limitations under a “pioneer patent” doctrine? This is not academic, since a substantial percentage of patent suit appeals at the Fed. Cir. are from S.J.s of non-infringement with no validity determinations, and IPR appeals arrive at the Fed. Cir. with no infringement considerations.

If the Fed. Cir. had not gone Egyptian with an ordinary observer infringement test for design patent claims [that seems more appropriate for trade dress cases] and if the PTO made design patent claim 103 rejections, this might be less of a problem?

But, of course, the problem that since a design patent claim is only a collection of shaped solid lines, with no distinguishing or limiting words, one has to have some clue as to how far the shape of the same parts of the accused product is from the shape of those lines in the design patent and still be infringing, since almost nothing would ever literally infringe by full line to line identity, hence the need to have some clue as to how close the prior art is already to those patent drawing lines.

since a design patent claim is only a collection of shaped solid lines, with no distinguishing or limiting words, one has to have some clue as to how far the shape of the same parts of the accused product is from the shape of those lines in the design patent and still be infringing, since almost nothing would ever literally infringe by full line to line identity, hence the need to have some clue as to how close the prior art is already to those patent drawing lines.

Excellent points. The PTO, of course, has no knowledge of and no meaningful access to any of that prior art, nor does it even have in place a sensible and coherent process for searching for that, or a sensible and coherent process for examination in view of the piddling amount art that it does manage to find.

And that’s the reason, of course, that David Kappos and others are promoting design patents as “the next big thing.” It’s just a playground for abuse and we can rest 100% assured that the worst is yet to come. Fixing the design patent system is going to make the subject matter eligibility “controversy” look like a cake walk.

Here is are two more reason why design patent infringement determination is difficult, not analogous to utility patent infringement determination, and thus needs different treatment:

There is no specification, hence no help from that for any intrinsic claim scope determination. [In some cases the title might be field-limiting, and some design patents issue with some disclaimers.]

There is also almost no prosecution history claim scope interpretation help since almost all design patents issue without substantive rejections or substantive amendments.

Thus it is surprising that more IPRs have not been filed against asserted design patents, since usually there is no prior art already of record in the design application prosecution, and the 103 test is under the same 103 statute – a POSITA [product designer] obviousness test, not an ordinary observer test.

Why do you assume that “In The Art” means [product designer]…?

Why do you think that it cannot mean “ordinary observer”…?

There is ample room to argue that since utility is not in the equation, the “utility” of a product designer makes that choice less meaningful – not more apt.

…do you think that “In The Art” necessarily means

more in the art of “inventing”…

or

more in the art of “using” the item so “invented”…?

I think that your view tends to the trap of placing that legal person on a slippery slope of being the inventor as opposed to being someone in the art. This is a problem with the utility patents as well, and I am reminded of a Gary Larson cartoon (iirc) of an astronaut punching a timeclock on his way to his spacecraft…

Paul,

Another reason that design patent infringement determination is difficult and very different from utility patent infringement is because designs are subjective, while utility patent inventions are by and large objective. And the courts, including our dear CAFC, whose docket consists 99% of utility patent cases, are constantly trying to objectify design patent infringement analysis, because this is what they are used to doing. And of course, there has to be some way to analyze a design patent case. I would submit that the best way to analyze design patent infringement is to give it to the jury, a perfect collection of ordinary observers, and have them come back with a verdict (see the Braun case from 1992).

Perry,

Paul first must come to the understanding of who the “person” in PHOSITA is.

As my posts cut to the chase, using different “persons” will give vastly different results.

Paul, I agree that different “persons” will give different results (although in reality the “person” is the judge, or his/her law clerks, or housekeeper). Legally speaking, the “person” for design patents is a designer of ordinary skill, see in re Nalbandian. The CAFC in International Seaway (a disaster of a case) became confused in thinking that obviousness should be judged by an ordinary observer, but they righted the ship in a footnote in the High Point decision from 2013.

Thanks Perry – so Paul is closer to the mark as to “what” (or who) the person “is.”

But does the current designation of “is” make sense from the questions I have asked?

Why is “designer of ordinary skill” chosen as the correct mark? Is the corollary in the utility world the inventor? Or is it rather someone else?

Anon,

Yep. The PHOSITA person in design patents is a designer (Nalbandian). It’s too bad that 35 USC doesn’t refer to a designer rather than inventor, or a design rather than an invention, but there’s a lot in 35 USC that could use spiffing up when it comes to design patents (patent law’s forgotten stepchild – until Apple-Samsung came along). (my previous post was directed towards your comment, not Paul’s).

Thanks again Perry – I have often noticed that the lack of rigor when it comes to design patents creates many problems.

But if Congress has been quiet about those differences, is it really up to the courts to shape the law and create differences that are not there? I “get” the court’s “hand” in the cases you mention – my question goes deeper than that. My question goes to the rather obvious parallels that – on their face – Congress has dictated by not being more particular with design patents.

I do not see in the statutes the ability or invitation to create a different PHOSITA for utility and for design patents.

We already have a subtle but real crises in the utility world with the mistake of thinking that PHOSITA includes inventors. That slippery slope path leads (and quickly so) to the expressly disavowed Flash of Genius standard.

Is not it common sense then to consider that design patents, being expressly non-utilitarian, should be even more wary of embracing a standard based on utilitarian skill? Ordinary skill then, not being the utilitarian skill leaves but the rest of the denizens of the particular arts, right?

I do not have the answer – I do have logic and that is what I have put on the table for dialogue.

Paul, the way I see it this:

Like the copyright abstraction filtration test, one has to compare the claimed design with its nearest examples, and then see if the accused design copies the unique features or the routine.

Regarding IPRs, I think one needs standing to challenge a patent and that the validity challenges can only take place in court. Claim construction is the same there for validity and infringement.

Did you know that the Supreme Court repeatedly held that the government has no standing to challenge the validity of a patent unless they are accused of infringement or if they were lied to by the patent applicant? The last such case came out just before congress enacted reexaminations.

Since Art. III standing is required even for an appeal, the government has no Art. III standing in an appeal from a reexamination or from an IPR.

The whole house of cards is going to fall, Paul.

It is a wonder to me that the patent bar is so ignor ant of Con Law — either that or they just don’t give a damn, in the words of Rhett Butler. Reexaminations, after all, boost the bottom line of patent law firms.

It comes across as more than just a little hollow this “so ignor ant of Con Law” from you and your false elevation of the Royal Nine and their common law above the Legislature and their statutory law, Ned.

Thank you, Paul.

The panel [in an otherwise lengthy opinion on other patents] spent remarkably few words on the key issue of the non-infringement of the design patents. Simply concluding that the designs were plainly dissimilar. There was no discussion of the scope of a design patent claim. As prior decisions have noted, that is defined by the solid lines of the patent drawings, and thus essentially narrow. But at least, by clear example, requiring the comparison of those drawings to the accused product and approving the judge determining if infringement is even legally assertable. [This was a bench trial, but that could make a significant difference to a jury trial.

As to the functionality issue, this is not the only area of Fed. Cir. design patent decisions where, as noted, “the panel attempted to harmonize the conflicting precedents.” Per an earlier blog on this website that was also the case for 103.

In deciding that the designs were invalid as functional, the district court relied on a number of factors from Berry Sterling Corp. v. Pescor Plastics, Inc. In Berry Sterling, the Federal Circuit stated that, in addition to the existence of alternative designs:

Other appropriate considerations might include: whether the protected design represents the best design; whether alternative designs would adversely affect the utility of the specified article; whether there are any concomitant utility patents; whether the advertising touts particular features of the design as having specific utility; and whether there are any elements in the design or an overall appearance clearly not dictated by function.

Most of this makes some sense but what on earth is the Federal Circuit thinking when it wades into the swamp of determining whether the protected design is “the best design”?

We’re talking about protecting ornamentation, not functionality. Presumably the “best design”, then, is the one that subjectively pleases people who gaze upon it but who have no knowledge of its functionality (or lack thereof). Is this going to be something for pollsters to do, or is it going to be one of those deals where each side hires some “expert” mouthpiece to present his/her paid-for and super informed opinion on the subjective beauty of the design?

For once, MM makes sense when talking about design patents. It is indeed foolishness for the court to wade into a “best design” analysis for functionality. In fact, the entire list of Berry Sterling “factors” are dicta, no court had used them before, and only one or two since. Indeed, they are the factors used in analyzing trade dress functionality (see Morton-Norwich), not design patent functionality, and probably appeared in Berry Sterling, at the very end of the opinion, as a result of improvident legal research. Kudos to the Federal Circuit for putting those factors in their place, very subservient to alternate designs. I submit that the existence of alternate designs that perform a substantially similar function should not be the main factor in analyzing design patent functionality, it should be the only factor, since it goes to the heart of why there’s a functionality doctrine in the first place. This decision is the second well-reasoned functionality opinion by the Federal Circuit in as many years, the first being High Point from 2013.

Maybe I am missing something here but those two images look plainly similar (i.e. not plainly dissimilar). If you compare the portions of the design patent which show solid lines to those equivalent parts on the alleged infringe, to me they seem not only equivalent but identical. Thoughts?

Mike,

Looking at the trigger by itself, an ordinary purchaser would probably buy one thinking it is the other as with the silverware in Gorham Co. v. White. However, the claimed design includes the underlying trigger, torque knob, and activation button. The illustrations here are a bit too subtle to show up the differences. Also, what the court did, which will infuriate design patent holders, is subtract out the functional aspects, namely the U-shape. Thus, if one looks carefully, the accused infringer’s U-shaped trigger has a dissimilar appearance to the U-shaped trigger in the design. Likewise, the activation button is rectangular vs. football-shaped in the design. No comment on the torque nut.

Mike, in the abstract sense, the two handles are “similar”. For instance, if you gave those two handle pictures two a five year old along with a picture of an apple, a zebra and the Empire State Building and asked the five year old which two pictures were most “similar”, the average five year old would pick the two handle pictures.

But in the design patent sense, the two designs are plainly different. The most obvious differences are the undulations of the patented design and the greater width of the top “hook” in the patented design. If adults want to own more “design”, they need to learn how to draw more purty pictures. Luckily the PTO basically operates at the kindergarten level when it comes to evaluating design patents so it shouldn’t be too tough.

Our design patent system remains a vastly greater joke than the utility patent system — and that’s a tough trick to pull off. Is it trying to fix itself? Maybe. At this rate, give the courts another hundred years. Actually make it two hundred because we can rest assured that the PTO will be fighting for its “clients” the entire way.

Thank you very much.

You’re not missing something here, Mike. As good as the Court’s opinion was on functionality, it was horrible on infringement. SB, the Court did not clarify anything about design patent infringement, it simply made it much easier for courts to grant summary judgment of non-infringement for accused infringers (which based on your tweets should please you). Egyptian Goddess did away with the point of novelty test, which compared the patented design with the prior art. The point of novelty test was unworkable, mainly because the Court had never said how it was to be applied, so everyone applied it differently – it was a mess. But, it was the only part of the two-part test for design patent infringement at that time (pre-2008) that had any objectivity – it at least looked at the prior art. The other part of the two part test was the Gorham ordinary observer test, which was (and is) highly subjective. How is a judge supposed to determine the outcome of the Gorham ordinary observer test, which is basically whether two designs appear to the eye as substantially the same? By simply looking at them? By asking his/her law clerks? By taking them home and asking his/her partner? By asking the housekeeper? Or gardener? Really, think about it. There is no way to objectively conclude that two designs are or are not substantially the same (of course, I agree that comparing an ash tray to a bicycle, or a transmission to a chair, should not require reference to the prior art). The lack of objectivity in the old Gorham test is why the court in Egyptian modified Gorham in requiring the ordinary observer to view the patented and accused designs “in the context of the prior art”. This was a realization by the Court that in eliminating the point of novelty test, they needed to re-inject some objectivity in determining design patent infringement, lest Gorham be decided at the whim of the decider, or by his/her housekeeper. The Court in Egyptian discussed 6 or 7 factors that the trier of fact could use in determining what “in the context of the prior art” meant. One factor of the 6 or 7 unfortunately said that if two designs are sufficiently distinct “that without more” would justify a finding of non-infringement. There were no guidelines about what “sufficiently distinct” meant, which led to many, many post-2008 district court opinions concluding that two designs were sufficiently distinct, granting accused infringers’ motions for summary judgment of non-infringement. Why do courts do this? Because it’s much easier than analyzing the prior art. And courts have full dockets. And they dislike patent cases. It’s the same reason, really, that courts loved the Federal Circuit’s pronouncement in Egyptian that abolished the necessity of a detailed verbalization of a claimed design during Markman claim construction. Regarding the latter, the Federal Circuit said that courts could provide a detailed verbalization if they wished, but they didn’t have to. So, do you think that any court went to the trouble of providing a detailed design patent claim verbalization post-2008? Of course not. And for this same reason, a court will avoid analyzing the prior art in determining infringement. If they don’t have to do something, they won’t. And they don’t have to look at the prior art if they find the two designs “sufficiently distinct”. Pre-Egyptian, the point of novelty test and detailed verbalization of claimed designs were the best two ways for accused infringers to avoid a finding of infringement. Those loopholes have been eliminated by Egyptian (yay), replaced by the “sufficiently distinct” loophole (boo). I will note that the Federal Circuit did have a moment of lucidity in the Revision Military case awhile ago in which it remanded a lower court’s finding that two designs were sufficiently distinct, instructing it to consider the prior art. Really, if you don’t look at the prior art, how in the world is the trier of fact supposed to determine the scope of a claimed design? It’s guesswork, at best, unless we’re talking about transmissions and chairs. In my view, comparing transmissions and chairs, or the like, was the rationale for the “sufficiently distinct” doctrine. But accused infringers, and busy courts, have latched onto it, ignoring the Federal Circuit’s requirement to judge similarity “in the context of the prior art”. Sigh.

I just wanted to make it clear that every one of the 6 or 7 factors discussed by the Court in Egyptian required some comparison to the prior art – but for the “sufficiently distinct” factor.

Thanks Perry.

PS: courts loved the Federal Circuit’s pronouncement in Egyptian that abolished the necessity of a detailed verbalization of a claimed design during Markman claim construction. …. If they don’t have to do something, they won’t. And they don’t have to look at the prior art if they find the two designs “sufficiently distinct”.

Let’s set aside for the moment the issue of what exactly “detailed” is supposed to mean in the context of “detailed verbalization of claimed design.” I don’t think courts have an issue at all with the idea of providing some verbalization of their reasoning for finding non-infringement (if they do, that’s a much larger issue than the design patent issue).

The CAFC’s rule that rendered a “detailed verbalization” optional in certain circumstances makes perfect sense in terms of both fairness and judicial economy. For instance, why bother with a “detailed verbalization” of a complex patented design that is asserted against a far simpler design that no reasonably person could find infringing? Why is any more detailed analysis necessary beyond, say, “the patented design consists of five complex polygons and the defendant’s consists of one circle”? It doesn’t matter what the prior art is. There is no more analysis required. Requiring more consideration of additional “factors” in such circumstances just increases the cost to defendants. If courts want to create those kinds of “required” considerations than they better have lengthy briefing on the underlying rationales and policy issues going to into such considerations.

Otherwise we end up with pointless and harmful nonsense like considering whether the design was “licensed” when determining its obviousness under 103.

MM, I cannot believe we are in agreement twice in the same post.

For “detailed” see the pre-2008 Minka Lighting case, where during Markman claim construction the court spent several pages writing a literal picture claim for a ceiling fan, a claim that no reasonable finder of fact would find infringed, even by a knock-off that changed only one or two elements.

The CAFC made design verbalization optional in Egyptian, and guess what? No court – save one or two – since 2008 has taken the trouble to do it. Nearly all design patent claim constructions consist of: “The ornamental design of a gizmo, as shown in FIGS. 1-6”. And this is perfectly rational, because subjective designs simply cannot be reduced to objective words. For example, 10 people looking at the Mona Lisa would come up with 10 completely different ways of describing it in words (credit to Carani for this one).

And your example of five complex polygons vs. a circle – albeit in the infringement context – is exactly what I think the Court meant by “sufficiently distinct” that requires no consideration of the prior art.

Way to go, Malcolm!

Sadly, you congratulate too quickly.

Anything so “sufficiently distinct” would not find its way to the court room in the first place, thus the direction from the court is quite meaningless because the direction needs to be for those cases not so “sufficiently distinct.”

A little closer to that zone of grey (and not an example so clearly different as to be unenlightening to a case that may actually be before a court), please.

At the other end of the spectrum are the cases where the accused design is so similar to the patented designs that the case doesn’t make its way to the courtroom.

The “zone is grey” is the very Ethicon case of which Prof. Burstein writes. I can’t tell if the designs infringe without looking at the prior art, can you? The Court didn’t give any context to its conclusion of no infringement, because it never considered the prior art.

Ethicon argued that they were not plainly dissimilar and that the district court erred in not considering the prior art, “which Ethicon characterizes as predominantly featuring thumb-ring and loop-shaped triggers.”

“Predominantly”?

ROTFMALO