by Dennis Crouch

In Energy Heating v. Heat On-The-Fly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the lower court's holding that Heat On-The-Fly's U.S. Patent No. 8,171,993 is unenforceable due to inequitable conduct.

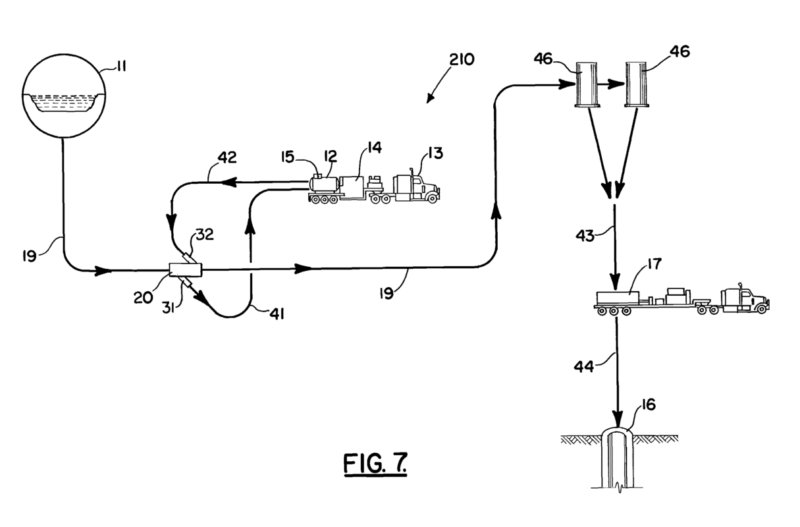

The underlying invention involves a portable system for preparing a heated water and proppant (e.g. sand) mixture for use in hydraulic fracing. Mr. Hefley, sole inventor and founder of Heat On-The-Fly, filed his priority provisional patent application back in September 2009 that eventually led to the '993 patent.

The problem: By September 2008 (one year before filing), Heafly and his company had provided his services to dozens of "frac jobs" -- collecting almost $2 million in revenue.

Mr. Hefley admitted at trial that he and his companies used water-heating systems containing all the elements of claim 1 on at least 61 frac jobs before the critical date. The court further found that invoices reflected that Mr. Hefley’s companies collected over $1.8 million for those pre-critical date heat-on-the-fly services.Those pre-filing jobs were not disclosed to the USPTO while the '993's application was pending - even though they appear quite material under 102(b) (Pre-AIA).

35 U.S.C. 102(b) (Pre-AIA) A person shall be entitled to a patent unless — (b) the invention was ... on sale in this country, more than one year prior to the date of the application for patent in the United States.Under Pfaff, the "on sale" bar requires (1) a "commercial" sale or offer and (2) the invention be "ready for patenting." Pfaff v. Wells Elecs., Inc., 525 U.S. 55 (1998). One exception to this rule is for "bona fide experiments." In particular, the Federal Circuit has held that experiments to "(1) test the claimed features or (2) determine if the invention would work for its intended use . . . will not serve as a bar." Citing Clock Spring, L.P. v. Wrapmaster, Inc., 560 F.3d 1317 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

Inequitable Conduct: In the failure-to-disclose context inequitable conduct requires clear and convincing evidence that "the applicant knew of ... the prior commercial sale, knew that it was material, and made a deliberate decision to withhold it." See Therasense. These issues are determined by the district court judge and given deference on appeal. Thus, an inequitable conduct finding should only be overturned when based upon a misapplication of law or based upon a clearly erroneous finding of fact.

Here, the patentee argued that the prior uses were "experimental" or at least he thought that they were. That argument was rejected since the prior uses included all elements of claim 1; that there were no notebooks or other experiment-like-paraphernalia; and that the uses were done openly without any attempt to hide the system or require confidentiality. (Linking these factors to Allen Engineering Corp. v. Bartell Industries, Inc., 299 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2002)). Those elements were more than enough to overcome the experimental-use-defense.

On Attorney Advice: The court also affirmed that Hefley knew of the materiality. On this point, the interesting twist involve's Hefley's patent attorney Seth Nehrbass. Nehrbass was not permitted to testify at trial -- but would have apparently testified that the non-disclosure was on attorney advice:

HOTF asserts that Mr. Nehrbass would have testified that Mr. Hefley told him about the 61 frac jobs, but that Mr. Nehrbass decided they were all experimental uses that need not be disclosed.This testimony might have saved the patent from the inequitable conduct finding. However, it was properly excluded on prejudice grounds. In particular, up until just before trial Hefley had asserted attorney-client-privilege (including during the Nehrbass and Hefley depositions). Then, just before trial, Hefley attempted to raise the attorney-advice defense.

We conclude that the district court did not abuse its discretion in excluding Mr. Nehrbass’s testimony. The attorney-client privilege cannot be used as both a sword and a shield. HOTF was the one who asserted the attorney-client privilege in the first instance and was also the one who failed to follow up later by deposing or otherwise making Mr. Nehrbass available for examination prior to trial. HOTF cannot have it both ways. Accordingly, we conclude that the district court did not abuse its discretion in excluding this evidence on HOTF’s advice of counsel defense.Inequitable conduct affirmed. Because inequitable conduct wiped-out all of the patented claims, the court did not reach the other patent questions of "obviousness, claim construction, and divided infringement.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.