by Dennis Crouch

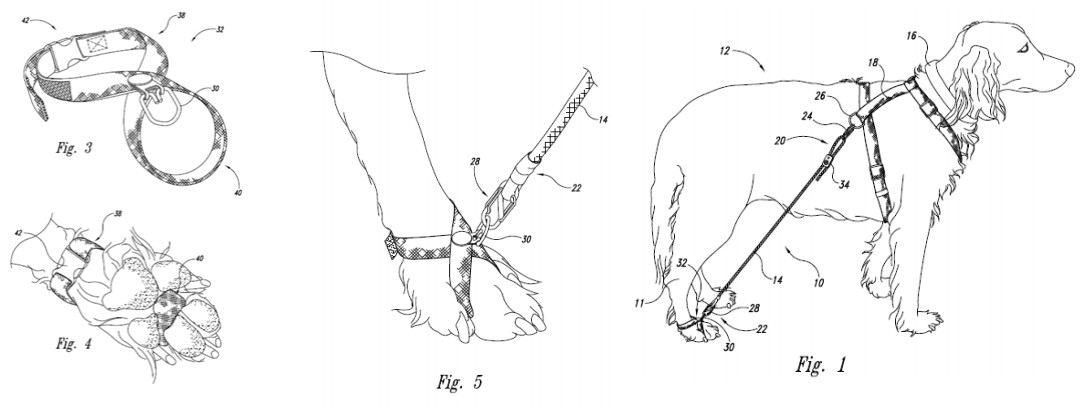

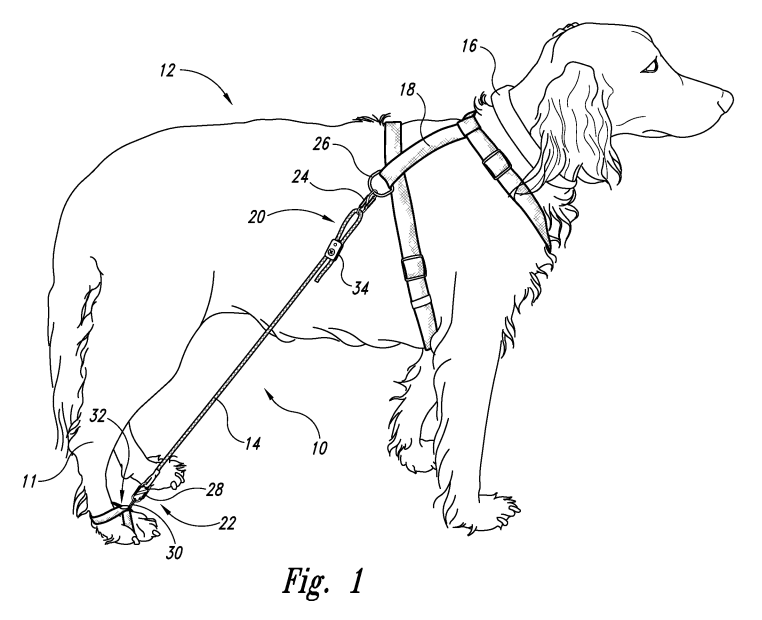

In re VerHoef (Fed. Cir. 2018) is a sad tale of a failed partnership that doomed the patent rights. The tale may be useful for anyone representing co-inventors involved in a start-up. At a minimum, a corporate entity should have been created at the get-go to hold the patent rights and mitigate later breakdowns in the partnership. Notice the drawing below - even the dog looks sad.

= = = =

For patent applications filed prior to the America Invents Act implementation, the Patent Act included an express requirement that the patent applicant be the inventor.

The named in inventor in this case - Jeff VerHoef - received some help from a veterinarian Dr. Lamb. In particular, VerHoef first designed and built his prototype harness designed to provide 'knuckling' therapy for his dog. Later, during a therapy session with Dr. Lamb, she suggested he consider a "figure 8" strap around the dog's toes. VorHoef implemented the idea then filed for patent protection -- naming both himself and Dr. Lamb as co-inventors.

Several months later, relations between VerHoef and Lamb broke-down; their original application was abandoned; and each filed their own separate patent applications. Both applications were filed on December 16, 2011 and are identical except for the names of the listed inventors.

Compare Pub. No. 20130152873 (VerHoef - at issue here) with Pub No. 20130152870 (Lamb - now abandoned).VerHoef's examiner examiner uncovered the parallel Lamb Application and subsequently rejected the claims under Section 102(f) -- alleging that Lamb's application provides evidence that "applicant did not invent the claimed subject matter." The PTAB affirmed that ruling and on appeal here the Federal Circuit has also affirmed.

For joint-inventorship, the baseline principles revolve around "conception." Individuals who conceive of features that lead to the whole invention are generally thought of as proper joint-inventors. However, the exact penumbra of what counts as sufficient contribution is at times difficult to exactly discern. Some cases suggest "every feature" while others require "significant contribution" as compared with the invention as a whole. Here the court did not need to parse-out the exact limits. Rather, VerHoef admitted that the figure-eight design (1) was contributed by Lamb and (2) is an "essential feature" of the invention.

VerHoef argued that he is the sole-inventor since he "maintained intellectual domination and control over the work" at all times and since Lamb “freely volunteered” the idea of the figure eight loop during a therapy session. ("Lamb's “naked idea was emancipated when she freely gave it to VerHoef.”)

The domination legal theory here from an old patent board decision, Morse v. Porter, 155 U.S.P.Q. 280 (B.P.A.I. 1965). In Porter, the Board wrote that if an inventor “maintains intellectual domination of the work of making the invention . . . he does not lose his quality as inventor by reason of having received a suggestion or material from another even if such suggestion proves to be the key that unlocks his problem.” Porter is cited by the Patent Office MPEP inventorship section as the basis for the following heading:

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.