Guest Post by Victoria T. Carrington and Professor Jorge L. Contreras.

Background

It should be no surprise to readers of Patently-O that many are unhappy with the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence regarding patent eligibility under Section 101 of the Patent Act. In response to various calls for “reform” of patent eligibility jurisprudence, on March 5, 2021, Senators Thom Tillis (R-NC), Mazie Hirono (D-HI), Tom Cotton (R-AR), and Christopher Coons (D-DE) requested that the US Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) conduct a study regarding public views on “how the current jurisprudence has adversely impacted investment and innovation in critical technologies like quantum computing, artificial intelligence, precision medicine, diagnostic methods, and pharmaceutical treatments.” The Senators also asked the PTO to evaluate the responses and provide a detailed summary of its findings by March 5, 2022. The PTO released its public request for information (RFI) on July 9, 2021. The original deadline for response was September 7, 2021, which the PTO extended until October 15, 2021. A total of 145 comments were submitted before the deadline. In advance of the official assessment, we have reviewed and tallied these public comments for those who are eager for the results in advance of the official release.

Methodology

We reviewed each submission that was made in response to the PTO’s 2021 Patent Eligibility RFI, as posted by the USPTO on Regulations.gov. Information that we noted and tracked included submitter name, submitter industry/specialty, date submission received, submitter location (if listed), and the general tenor of the submitter’s comments.

Findings

Demographics

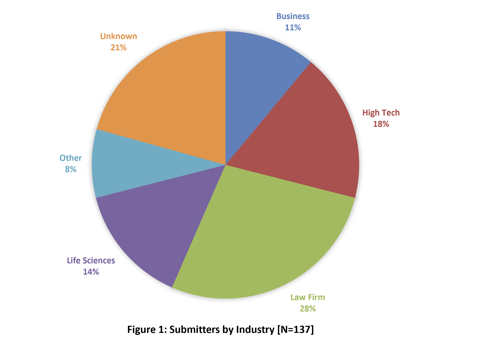

There was a total of 145 submissions. Some individuals submitted two comments, and one individual submitted four identical comments. Fifteen submissions were anonymous. We combined multiple submissions from the same commenter, yielding a total of 137 unique comments.

Figure 1 below shows the breakdown of industry affiliation of submitters. The largest group of submitters (28%) were patent attorneys and/or law firms that did not have a clear industry affiliation. Companies and trade associations were broadly classified as “High Tech” (18%) or “Life Sciences” (14%). Submissions classified as “Business” (11%) identify those made by venture capitalists and submitters focused on finance or entrepreneurship like the Market Institute. “Other” (8%) industries represented included cross-industry trade associations such as the Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM) as well as individuals, organizations, and companies that otherwise did not readily fit into the other specified classifications such as the mining conglomerate Rio Tinto, and Acushnet, a which makes golf equipment and apparel.

Sixty-three submitters specified a location. California had the highest number of submissions (11). Six submissions came from outside of the U.S.: Canada, Japan, Macedonia, Switzerland, and two from the United Kingdom.

Analysis of Positions

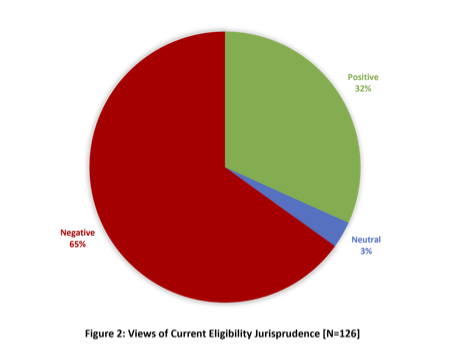

We analyzed the content of each submission to determine whether the submitter generally viewed current jurisprudence regarding patent eligibility in a positive or a negative light or adopted a neutral stance. Figure 2 below illustrates the breakdown of submissions among these categories, excluding 19 submissions that did not actually address the question of patent eligibility.

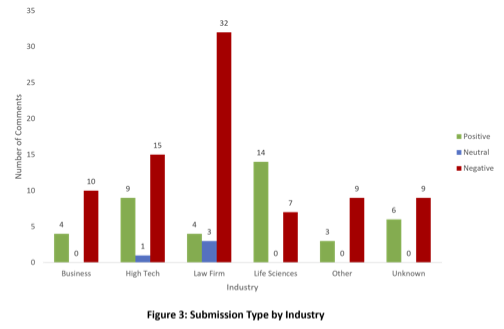

Figure 3 shows the comparison of the general tenor of submissions made by industry classification.

Below we discuss these findings in more detail.

Neutral Comments

Four submissions adopted a neutral standpoint, neither praising nor criticizing current patent eligibility jurisprudence. One such comment was submitted by Professors Maya M. Durvasula, Lisa Larrimore Ouellette, and Heidi L. Williams. It effectively critiques the empirical validity of the PTO study itself: “Many have argued—largely based on anecdotes or descriptive data—that recent changes in patent eligibility caselaw have either increased or decreased innovation. Here . . . we argue that neither view is supported by the available empirical evidence.” “It is unclear whether limits on patent eligibility increase or decrease innovation.” “Current evidence does not demonstrate whether the Alice/Mayo framework is good or bad for social welfare in contested fields [specifically the biomedical and software markets].”

Positive Comments

Forty submissions (27.6%) describe current patent eligibility jurisprudence in a positive light, noting general satisfaction with the Supreme Court’s eligibility case law and its application within the market. Notable commenters in this camp include the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Google, and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).

The ACLU also criticized the framing of the PTO study, observing that “[t]roublingly, the RFI seems to adopt the same framing as the Senators’ request, presupposing that patent-eligibility jurisprudence lacks clarity and consistent application and that this lack of clarity is causing harms. Neither the Senators’ letter nor the RFI provides any basis for the allegation that the law is inconsistent or unclear . . . .” The ACLU points to the fact that there is a high affirmance rate of subject matter eligibility decisions made by district courts and the PTAB to argue that current patent eligibility jurisprudence is relatively clear. It also points to statements in Federal Circuit Opinions showing that judges are able to apply 101 in a clear and consistent manner.

Google commented that “robust data supports that the balance in our IP system has allowed patenting in emerging technologies to flourish. . . . We urge the PTO to reject the premise set forth in the RFI that ‘the current jurisprudence has adversely impacted investment and innovation in critical technologies like quantum computing and artificial intelligence.’”

From the life and health sciences perspective, the AAMC drew on public health and access considerations, noting “that law and policy must protect and balance the public good, including access to timely patient care, with proprietary rights in support of science and technology, particularly in the fields of medicine and public health. We believe that these principles are reflected in current jurisprudence.”

Negative Comments

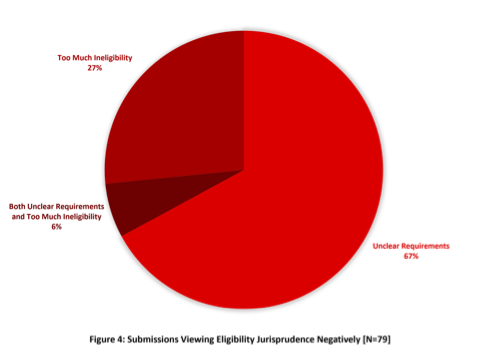

Eighty-two submissions (56.6%) expressed at least one major concern with the state of current patent eligibility jurisprudence. The two primary concerns were that (1) eligibility requirements are too unclear and/or uncertain and (2) too many useful inventions are currently ineligible for patent protection based on current eligibility requirements.

International Business Machines (IBM) specifically critiqued the judicially created ‘abstract idea’ exclusion from patent eligibility, noting that it “continue[s] to unnecessarily generate wide uncertainty about the validity of information technology patents and to undermine the patent incentive. It is a significant concern to innovators and patentees, who rely on the patent system to protect their investment in computer-related innovations. This uncertainty reduces public confidence in issued patents, making it harder for inventors to benefit from those patents.”

The “too-many-inventions-are-ineligible” camp includes the IP Law Section of the State Bar of Nevada. It specifically highlights that there has been an “[o]verly broad application of” In re Smith to reject electronic gaming machine inventions under Section 101.

Novartis’s submission sums up both reasons most submitters are unsatisfied with patent eligibility: the uncertainty and the ineligibility of specific important inventions.

Figure 4 illustrates the relative frequency of these different negative arguments made regarding patent eligibility.

Conclusion

This preliminary assessment shows a range of views expressed by public commenters in response to the PTO’s Section 101 Patent Eligibility Study. There is clearly no majority or consensus view, meaning that any legislative response to the dissatisfaction voiced by some over current judicial eligibility decisions should be taken with care and provide further opportunities for public input and debate.

The data for this post is archived at Victoria Carrington, 2022, “Public Comments on PTO’s 2021 Patent Eligibility Study”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DQWHHO, Harvard Dataverse, V1.