by Dennis Crouch

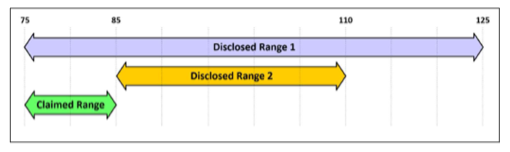

In a recent decision, the Federal Circuit held that a claimed range reciting narrower values than those described in the patent specification can still satisfy the written description requirement under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a). RAI Strategic Holdings, Inc. v. Philip Morris Prods. S.A., No. 22-1862 (Fed. Cir. Feb 9, 2024). Reversing a PTAB post-grant review decision, the court ruled that claims reciting a heating element with having a length of 75-85% of the disposable aerosol-forming substance had adequate written description support even though the specification only described broader ranges, such as “about 75% to about 125%.” Id.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.