by Dennis Crouch

In Sisvel v. TCT Mobile and Honeywell, the Federal Circuit has affirmed the PTAB's IPR findings that the claims are obvious. The non-precedential decision provides further insight into the Federal Circuit's reasonable expectation of success test.

Sisvel's U.S. Patent 8,971,279 covers a method of sending Semi-Persistent Scheduling (SPS) deactivation signals that essentially "piggyback" on existing messages. SPS is a technique used in LTE networks to more efficiently allocate radio resources to user equipment (UE) for periodic transmissions, such as Voice over IP (VoIP). In SPS, the base station pre-allocates resources to the UE for a set period of time, reducing the need for frequent scheduling requests and grants. SPS deactivation signals are messages sent by the base station to the UE to indicate that the pre-allocated resources are being released and are no longer available for the UE's periodic transmissions. These signals are necessary to free up the resources when they are no longer needed, allowing them to be reassigned to other UEs or used for other purposes.

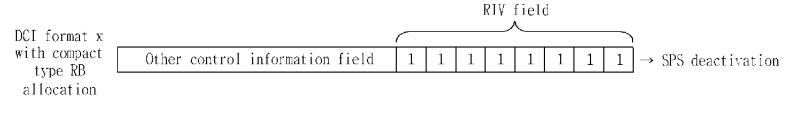

In the context of Sisvel's '279 patent, the invention was directed to a specific method of sending SPS deactivation signals by filling a preexisting binary field (the resource indication value or "RIV") with all "1"s. This 111111111 technique was intended to provide a more efficient way of signaling SPS deactivation while still ensuring that the deactivation message would not be mistaken for a valid resource allocation message. In the patented system, the string of ones would always be processed as an invalid value and never mistaken for a valid resource allocation message, providing stability to the network, regardless of size.

TCT Mobile and others petitioned for IPR, asserting that the challenged claims were obvious based on various combinations of prior art, including Samsung and Dahlman. The PTAB found the claims unpatentable as obvious, and Sisvel appealed.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.