by Dennis Crouch

In a nonprecedential disposition issued March 20, 2024, the Federal Circuit vacated a district court's denial of a permanent injunction to a patent owner, finding the lower court read Federal Circuit precedent too broadly to categorically preclude injunctions in situations where a patentee has a history of licensing the patent to third parties. In re California Expanded Metal Products Co., No. 2023-1140 (Fed Cir. Mar. 20, 2024). The decision reaffirms that the equitable framework laid out by the Supreme Court in eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C. requires a case-by-case analysis of irreparable harm and the other injunction factors, even when the patentee's business model relies on licensing revenue rather than direct competition in practicing the patents. 547 U.S. 388, 391 (2006). However, the decision may well be seen simply as distinguishing between exclusive and non-exclusive licensing approaches.

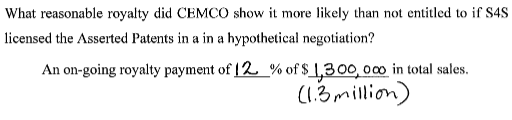

In its decision, the Federal Circuit also affirmed the district court's R.59(e) order setting aside the damages verdict -- meaning that although the patentee proved infringement, it will receive $0 in compensatory damages.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.