The Federal Circuit is set to hear oral arguments in November 2024 in Teva v. Amneal, No. 24-1936, a case that could significantly impact Orange Book patent listing (and delisting) practices under the Hatch-Waxman Act (formally known as the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984). Hatch-Waxman established a framework for generic drug approvals in the United States. It aims to balance incentives for pharmaceutical innovation with mechanisms to facilitate faster generic drug entry, including provisions for challenging patents listed in the FDA's Orange Book and offering a 180-day exclusivity incentive for first generic entrants. The Orange Book listing also comes with a powerful 30-month stay -- pausing generic entry - if the patentee sues a generic seeking FDA approval.

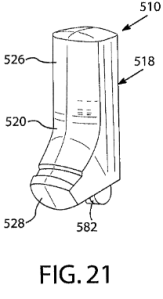

At issue are five patents related to Teva's ProAir HFA (albuterol sulfate) Inhalation Aerosol, a metered dose inhaler (MDI) product. The patents claim various aspects of the inhaler device and dose counter, but do not expressly recite the active ingredient albuterol sulfate. Teva listed these patents in the FDA's Orange Book for ProAir HFA. The big-money question in the case is whether these device patents are properly listed -- recognizing that the Orange Book is particularly for patents that claim either the drug or a method of using the drug.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.