by Dennis Crouch

In a significant victory for software patent applicants, the Federal Circuit reversed the a PTAB rejection of computer system claims in In re McFadden, 2024-2107 (Fed. Cir. Sept. 5, 2025). One problem with the decision is its non-precedential status – even though it clearly breaks new ground. The case offers another example of the potential power of 112(f) means-plus-function claims.

Brian McFadden’s U.S. Patent Application No. 16/231,749, claims systems and methods for location aware social media posting. The examiner had rejected claims 10-18 under § 101 as “software per se” without structural recitations, and claims 10-17 under § 112(b) as indefinite mixed claims reciting both apparatus limitations and method steps. The Board affirmed both of those rejections, but the Federal Circuit has now reversed on § 112(b) and vacated and remanded on § 101, ordering the Board to proceed with Alice/Mayo analysis rather than stopping at the statutory category inquiry.

McFadden’s claims do not recite any real structural limitations, but rather use broad non-technical words such as “a module” and “a subsystem.” The Board found these insufficiently concrete and thus identified the claims as directed to “software per se” without “a physical or tangible form” and thus did not fall within any Section 101 statutory category (process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter). On appeal, the Federal Circuit found these “nonce words” should be interpreted as means-plus-function and that recitation of corresponding generic computer hardware descriptions in the specification can provide sufficient structure to avoid “software per se” rejection.

The decision also has some interesting thoughts on indefiniteness for system claims that incorporate functional language, distinguishing between impermissible mixed system/method claims and permissible system capability claims.

Notably, McFadden pursued his patent and appeal pro se and won. Congratulations!

Claim 10 recites:

A social network system, comprising:

a post or other equivalent information item from a first user of the social network;

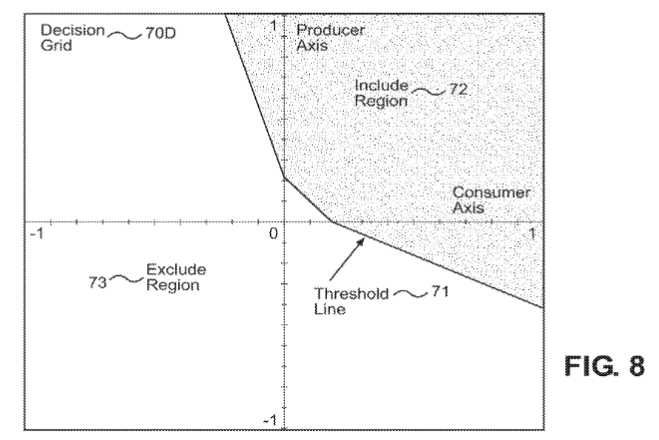

a subsystem configured to use the method of claim 1 to determine an include region for a second user of the social network; [and]

a module capable of using the include region to determine inclusion of the post into a news feed or equivalent information stream directed to the second user.

The Board had concluded that the claim constituted “software per se” because it did not “explicitly recite any limitations directed to hardware, such as circuitry, computers, CPUs, memory, or computer-readable storage medium” and did not “use the words ‘means’ or ‘step’ to tie the claim limitations to any hardware structure described in the Specification.” On appeal though, the Federal Circuit found this analysis fundamentally flawed because it failed to properly interpret the claims under 35 U.S.C. § 112(f).

Means-Plus-Function Primer: Patent claims typically must recite particular structural elements with sufficient specificity to define the invention's boundaries. However, 35 U.S.C. § 112(f) permits patent applicants to claim certain elements more broadly using functional language—traditionally as "means for [performing specified function]"—with the actual scope determined by examining the specification for corresponding structure that performs that function. While the classic trigger phrase is "means for," the Federal Circuit has extended this doctrine to apply to "nonce words" or generic terms like "module," "element," or "unit" that are essentially devoid of structural meaning, treating them as functional claiming subject to the same requirements for corresponding structure in the specification.

Although the claims did not use the word “means,” the Federal Circuit determined that the presumption against § 112(f) application was overcome because terms like “subsystem” and “module” were “devoid of particular structure” and failed to “recite sufficiently definite structure.” Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC, 792 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (en banc in part).

Having determined that § 112(f) applied, the court examined the specification to identify corresponding structure. The specification disclosed that the system “is computer coded software operating on a computer system” and elaborated that the computer system could be “any combination of one or more physical computer hardware systems, physical servers, devices, mobile devices, CPUs, auxiliary CPUs, embedded processors, workstations, desktop computers, virtual devices, virtual servers, virtual machines, or similarly related hardware.”

Although this hardware is fairly generic, the test for fitting in one of the statutory categories is formalistic — i.e., generic hardware is still hardware.

For the purposes of this specific inquiry under § 101—whether the claims at issue contain enough structure such that they do not constitute “software per se”—the alleged generic nature of the corresponding structure does not render the structure nonexistent.

Having found that the claims recite sufficient structure to fall within statutory categories, the Federal Circuit vacated the § 101 rejection and remanded for Alice/Mayo analysis. Importantly, the court issued this procedural suggestion:

Going forward, we encourage the Board to conduct an analysis under Alice/Mayo whenever presented with an examiner rejection under § 101.

This guidance suggests the Board has been improperly terminating § 101 analysis at the statutory category stage rather than proceeding to the more substantive abstract idea inquiry under Alice/Mayo. Although the statutory category stage is highly formalistic, the Alice/Mayo inquiry is not, and the generic computer technology may well be insufficient on remand.

Crouch’s BRI Rant: One oddity of the Court’s decision is that it did not discuss broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI), which may shape whether or not a particular word is interpreted as MPF or not. Although its name suggests otherwise, I argue BRI is not simply about stretching terms to their widest ‘reasonable’ scope. Rather, it embodies the PTO’s practice of considering a spectrum of reasonable constructions and then testing patentability against that set. In most situations the broadest of those constructions will expose any validity concerns, and so “broadest reasonable” remains an apt shorthand. But he analysis becomes trickier in some situations, such as McFadden when the term at issue is so generic that it flips into § 112(f). In those nonce-word contexts, a “broader” reading can paradoxically result in a narrower claim once tied back to the disclosed structures.

That discontinuity highlights why, in my opinion, BRI should not be treated as a mechanical maxim, but as a methodology of testing patentability against alternative plausible constructions. Examiners facing nonce-type terms should ask whether both the plain-language and § 112(f) interpretations are “reasonable,” and then analyze patentability under each. If either leads to problems of invalidity or indefiniteness, the applicant ought to face that tension head-on. The Federal Circuit in McFadden sidestepped BRI altogether, but its omission underscores the need for the PTO to integrate claim construction methodology into these § 101 and § 112 inquiries rather than treating them as wholly separate silos. Here, I believe the court identified what it thought was the ‘best’ construction, but in reviewing examination-stage patent applications, the approach should have been to consider reasonable constructions and ask whether any of those constructions render the claims invalid.

This methodology serves BRI’s fundamental purpose of ensuring that only genuinely patentable claims proceed to issuance by exposing potential invalidity or indefiniteness problems across the spectrum of reasonable interpretations. The prosecution stage represents the right time for this push-back because applicants have full flexibility to amend their claims in response to any identified deficiencies. BRI also serves somewhat to facilitate the notice function of patents by forcing applicants to clarify ambiguous claim language that might otherwise leave competitors uncertain about the scope of protection.

As a caveat, In re Donaldson Co., 16 F.3d 1189 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (en banc), seems to read BRI differently than I do — looking for the single correct broadest reasonable interpretation rather than considering a spectrum of potential reasonable meanings. I think that approach is misguided at the examination stage but it is the current black-letter rule, and examiners and the Board are bound to apply it.

Means Plus Function as the Solution to Eligibility Issues?: The case explains how the MPF approach overcomes certain eligibility hurdles. In my view, specified structure sufficient for 112(f) should be seen as evidence typically sufficient to overcome 101 eligibility rejections. The logic here is straightforward: if an applicant has identified concrete structure in the specification that performs the claimed functions, then the claim recites more than just abstract concepts. Of course, this strategy comes with trade-offs. Claims interpreted under § 112(f) are limited to the specific structures disclosed in the specification and their equivalents, potentially narrowing scope compared to broader functional language interpreted at face value.

Section 112(b) Indefiniteness: System Capabilities vs. User Actions

The Federal Circuit also reversed the Board’s § 112(b) indefiniteness rejection, clarifying important distinctions in the application of IPXL Holdings, L.L.C. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 430 F.3d 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2005). In IPXL, the court held that “a single claim covering both an apparatus and a method of use of that apparatus is invalid” as indefinite, because such claims create uncertainty about contributory infringement liability for manufacturers and sellers of claimed apparatus.

Here, the Federal Circuit distinguished the present claims from those found indefinite in IPXL and related cases. The key distinction lies between claim limitations “directed to user actions” versus limitations that describe system functionality.

Here, the claim 10 recites:

subsystem configured to use the method of claim 1 to determine an include region for a second user of the social network

The court found that the phrase “configured to” here was critical to its analysis and finding no IPXL problem. As the court explained, the claims “do not require performance of the method steps” but rather are directed to a system that possesses the structure and capability of performing the required steps.