By Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit has reversed a preliminary injunction order in a trade secret misappropriation case, finding that the district court abused its discretion by failing to properly evaluate the likelihood of success on the merits and the balance of harms. Insulet Corp. v. EOFlow, Co., No. 2024-1137 (Fed. Cir. June 17, 2024). The appellate court held that the district court's analysis was deficient in several key respects, including not addressing the statute of limitations defense, defining trade secrets too broadly, and not sufficiently assessing irreparable harm and the public interest.

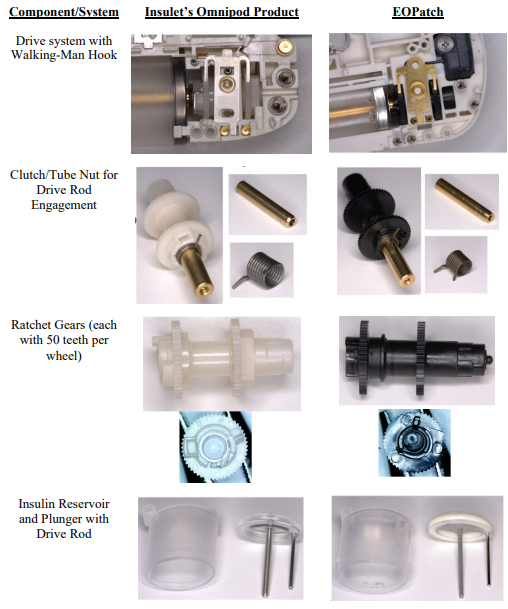

This classic trade secret case involves former employees left to join a competitor. As free humans, they are permitted to take their skill and wisdom to the new jobs, but are forbidden from misappropriating trade secret knowledge. That line drawing is particularly difficult, and one reason why many employers moved toward contractual non-compete agreements. The case is also complicated because the defendant here admit to reverse engineering that apparently lead to some substantial similarities between the products.

The decision highlights a high bar for obtaining a preliminary injunction, even in trade secret cases involving competitors where we previously may have assumed irreparable harm. The Federal Circuit here explained that lower courts are required to individually evaluate each of the four injunction factors - likelihood of success on the merits, irreparable harm, balance of hardships, and public interest. Conclusory assertions of competitive harm are insufficient to show irreparable injury. For trade secret claims in particular, the alleged trade secrets must be defined with specificity. But, this proof is often difficult at the preliminary injunction stage of a case when the particular knowledge used by the defendant has not been fully discovered.

The Federal Circuit has been seen as largely supporting strong trade secrecy rights. However, this decision may put a damper on forum shopping attempts.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.