by Dennis Crouch

In baseball, there is a folk rule on force-outs that "tie goes to the runner." The idea is straightforward: if the ball and the runner arrive at the base simultaneously, the runner is safe. In fact, the Official Rules of Baseball do not admit that a tie is even possible, but rather the question is simply whether the fielder tagged the base before the runner arrived. But the folk rule persists because it reflects an instinct about how close calls should break: and in baseball it is the fielder's duty to force the out.

Director John Squires has brought a version of this thinking to patent examination. Since taking office in September 2025, Squires has repeatedly signaled that close calls on patent eligibility should favor the applicant. The December 4, 2025 memoranda on Subject Matter Eligibility Declarations (SMEDs) formalized the invitation: applicants facing Section 101 rejections should submit evidentiary declarations under 37 C.F.R. § 1.132, and examiners should treat that evidence seriously when evaluating eligibility under the preponderance-of-the-evidence standard. Dennis Crouch, Subject Matter Eligibility Declarations (SMEDs) to Overcome Eligibility Rejections, Patently-O (Dec. 5, 2025). The theory is that a well-drafted SMED, supported by concrete technical evidence, should create enough disputed facts to tip the balance in the applicant's favor. But the question remains whether examiners on the ground will agree.

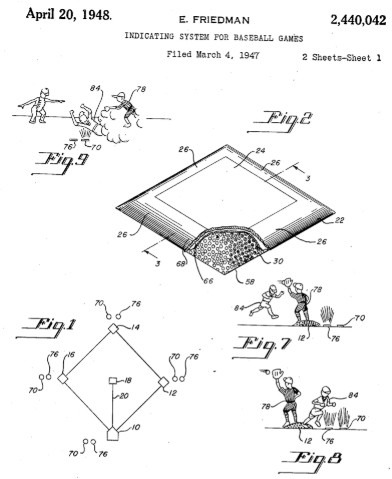

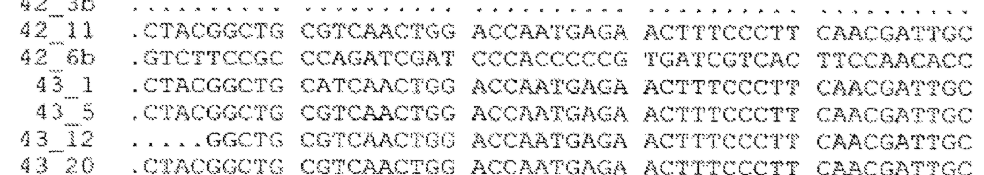

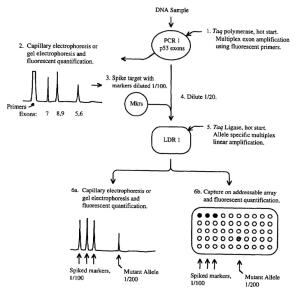

After looking through several hundred R. 132 declarations, I eventually found seven SMEDs that specifically target Section 101 eligibility. The sample is small but instructive. These seven declarations span a range of technologies: data center infrastructure automation, financial analytics, robotic process automation, cybersecurity risk modeling, plant genomics, and blockchain systems. The declarants range from solo inventors with decades of software experience to PhD scientists at venture-backed startups. And the early results are mixed. So far, none have received a notice of allowance and others have been rejected (with the bulk still awaiting response from the examiner).

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.