Do patents encourage economic growth, stimulate R&D investment, or deliver wealth to innovators? In our previous post we reviewed the empirical research in economics and we could not find consistently positive evidence about the performance of patents.

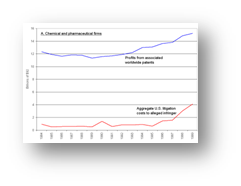

In this post we narrow our focus. We ask whether the modern American patent system encourages innovation by large (publicly traded) American firms. We answer this question with empirical research that is presented in chapters 5 and 6 of our book Patent Failure. We find that the patent system discourages investment in innovation by the average publicly traded American firm. Although the patent system provides positive incentives in some industries like pharmaceuticals, it provides negative incentives in most industries. Further, the performance has deteriorated over time.

Our conclusion is based on separate estimates of the benefits and costs of patents to innovative firms. We use two different techniques to estimate the value of patents to their owners.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.